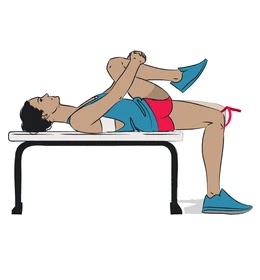

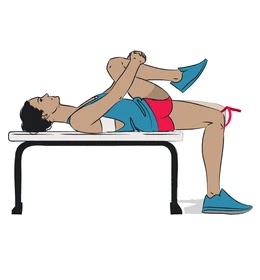

There is limited evidence that quadriceps flexibility is a risk factor for hamstring injury.

There is limited evidence that hip extension asymmetry >15% is associated with musculoskeletal injury.

There is moderate evidence of an association between hamstring flexibility and muscluloskeletal injury. Individuals with too short, or too long hamstrings are at a 3x risk of experiencing a hamstring injury.

There is moderate evidence that asymmetry in ankle flexion >6.4 degrees is associated with ~5x risk of experiencing a musculoskeletal injury.

There is moderate evidence that supports associated between lower body musculoskeletal risk and lower body power. However, some studies demonstrate an increased risk for both high and low power athletes. One study demonstrates that for army conscripts in Finland that had poor broad jump distances, were ~2x more likely to experience an injury. Another study demonstrated in professional male soccer players that had a higher vertical jump were 1.5x more likely to suffer a hamstring injury.

There is moderate evidence that slower sprint speed is associated with ~10x more likely to be injured than those with faster speeds at 10, 40 and 300 meters distances.

There is moderate evidence that demonstrates a 2.5x increased injury risk in ankle sprain injuries in athletes that have poor single leg balance.

Despite the growing field of research in injury assessment and risk management, there are quite a few unanswered questions. Standardization of measurements, sport-specific assessments, and more robust association in findings would help clear up many of these questions.

Practical application and programming for athletes and careers that require high fitness levels should also be discussed within the research community. Perhaps guidelines may help coaches develop pre-season injury assessments and provide strength and conditioning programs that are athlete-specific, essentially reducing the number of athletes sitting on the sidelines due to injury.

If you are an athlete or coach in Miami, FL and find this topic interesting, or want more information, reach out to our office for assistance.

Determining injury risk for athletes is a challenging task. While much research has been done in this field for decades, the mechanisms for assessing risk of injury have not been fully elucidated. General principles and guidelines have been adopted by clinicians, but these can vary widely by sport, gender, exercise history, injury history and a host of other intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

In this article we will discuss what the literature suggests in regards to how flexibility, speed, power, balance and agility may play a role in injury prevention. These findings are important to a large and heterogenous population. Individuals engaged in careers that require a high level of fitness (SWAT officers, FBI agents) and athletes can benefit from this research.

Organizations that manage tactical athletes (SWAT, FBI field agents) can better assess and develop physical fitness protocols using these markers as general guidelines for health and fitness. A large economic burden placed on the health system when officers are injured. Time off, changes in work duties, surgery and rehabilitation can drastically change the career trajectory of an injured agent.

Coaches can better program exercises for athletes and athletes can use these guidelines to help identify areas that need work.

Of important note, is that these values are not definitive. Being outside of a hypothetical “high risk” category, does not mean you will never be injured. Similarly, just because you are in a “high risk” category, does not mean you shouldn’t participate in sports or join a career that requires a high level of fitness.

Lets take a look at each category. For the sake of keeping things simple to digest, I will keep the description brief and delve into the geeky science stuff. If you wish to read the original article, you can find it here.

There is limited evidence that quadriceps flexibility is a risk factor for hamstring injury.

There is limited evidence that hip extension asymmetry >15% is associated with musculoskeletal injury.

There is moderate evidence of an association between hamstring flexibility and muscluloskeletal injury. Individuals with too short, or too long hamstrings are at a 3x risk of experiencing a hamstring injury.

There is moderate evidence that asymmetry in ankle flexion >6.4 degrees is associated with ~5x risk of experiencing a musculoskeletal injury.

There is moderate evidence that supports associated between lower body musculoskeletal risk and lower body power. However, some studies demonstrate an increased risk for both high and low power athletes. One study demonstrates that for army conscripts in Finland that had poor broad jump distances, were ~2x more likely to experience an injury. Another study demonstrated in professional male soccer players that had a higher vertical jump were 1.5x more likely to suffer a hamstring injury.

There is moderate evidence that slower sprint speed is associated with ~10x more likely to be injured than those with faster speeds at 10, 40 and 300 meters distances.

There is moderate evidence that demonstrates a 2.5x increased injury risk in ankle sprain injuries in athletes that have poor single leg balance.

Despite the growing field of research in injury assessment and risk management, there are quite a few unanswered questions. Standardization of measurements, sport-specific assessments, and more robust association in findings would help clear up many of these questions.

Practical application and programming for athletes and careers that require high fitness levels should also be discussed within the research community. Perhaps guidelines may help coaches develop pre-season injury assessments and provide strength and conditioning programs that are athlete-specific, essentially reducing the number of athletes sitting on the sidelines due to injury.

If you are an athlete or coach in Miami, FL and find this topic interesting, or want more information, reach out to our office for assistance.