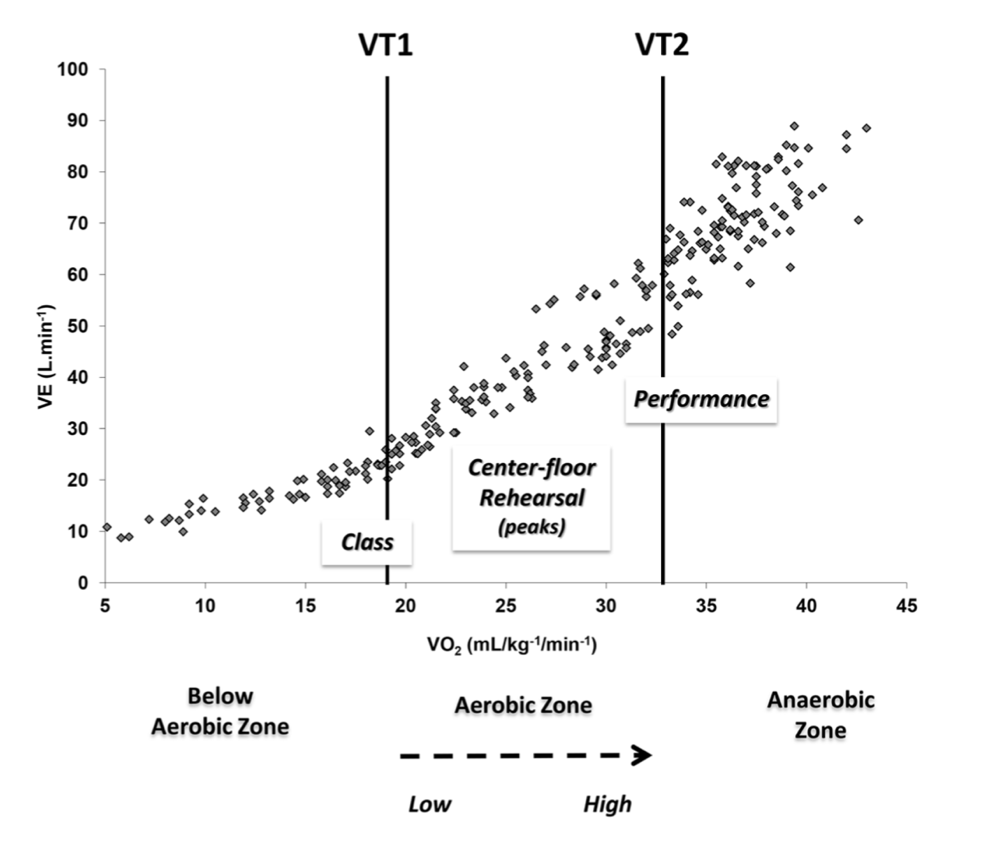

Rehearsals, after the creation and learning process, often place a higher cardiovascular demand on the dancer. This adaptations to this demand, however, may be too late in order to prepare the dancer for a specific performance. In addition, the total amount of time spent in this higher intensity zone is often limited. In professional ballet dancers, this was about 10% of total time in rehearsals.

4

Dancers, therefore, should train to optimize the contributions of the proper energy systems to improve their performance. This includes engaging in an exercise program that complements a dancers style, experience level and type of dance. Dance class and rehearsals often emphasizes technique and skill acquisition as opposed to strength and cardiovascular adaptations. Complementary fitness training should identify the strengths and weaknesses of the individual performer and develop a program that considers dance type, style and choreography of the show being rehearsed. Variables such as intensity, volume and frequency should be managed to avoid overtraining. Additional considerations should include total accumulation of classes, rehearsals and alternative body therapies. Researchers suggest that fitness training should not interfere with dancers’ technical work, thus, periodization strategies should be implemented.

One frequently visited concern for performers is a loss of an aesthetically pleasing body due to muscle hypertrophy, loss of joint flexibility and overall fatigue when rehearsing. There have been a number of studies that show this is not true. A study of 12 weeks of aerobic and strength training exercise improved dancers aerobic capacity, muscle strength and flexibility in addition to positive changes in dancers body composition. Another study demonstrated that one hour of circuit training and vibratory training twice a week improved muscle power, aerobic capacity and dance aesthetics more efficiently than adding one additional hour of extra dance class per day. Other programs that varied intensity and work to rest ratios in training a ballet performance improved fitness levels. High intensity interval training (HIIT) appears to be the proper mode of exercise for improving dancers aerobic power. Intermittent exercise bouts with a work to rest ratio of 1:1, exercise time 3-6 minutes, 90-95% of VO2 max, RPE 16-17 and active recovery at low aerobic intensity is the recommended approach. For dancers that have limited time to add supplementary training, it is suggested that one five minute session performed three days per week of HIIT 3×20 program can induce changes in the cardiovascular system. For example, three sets of 20 seconds of high intensity activity followed by a 2 minute active recovery at low intensity. The active recovery process maintains blood flow to the muscles and assists in removing metabolites from lactic-acidosis pathways. The authors of this study suggest moving through a Grand adage for dancers with high technical ability.

5

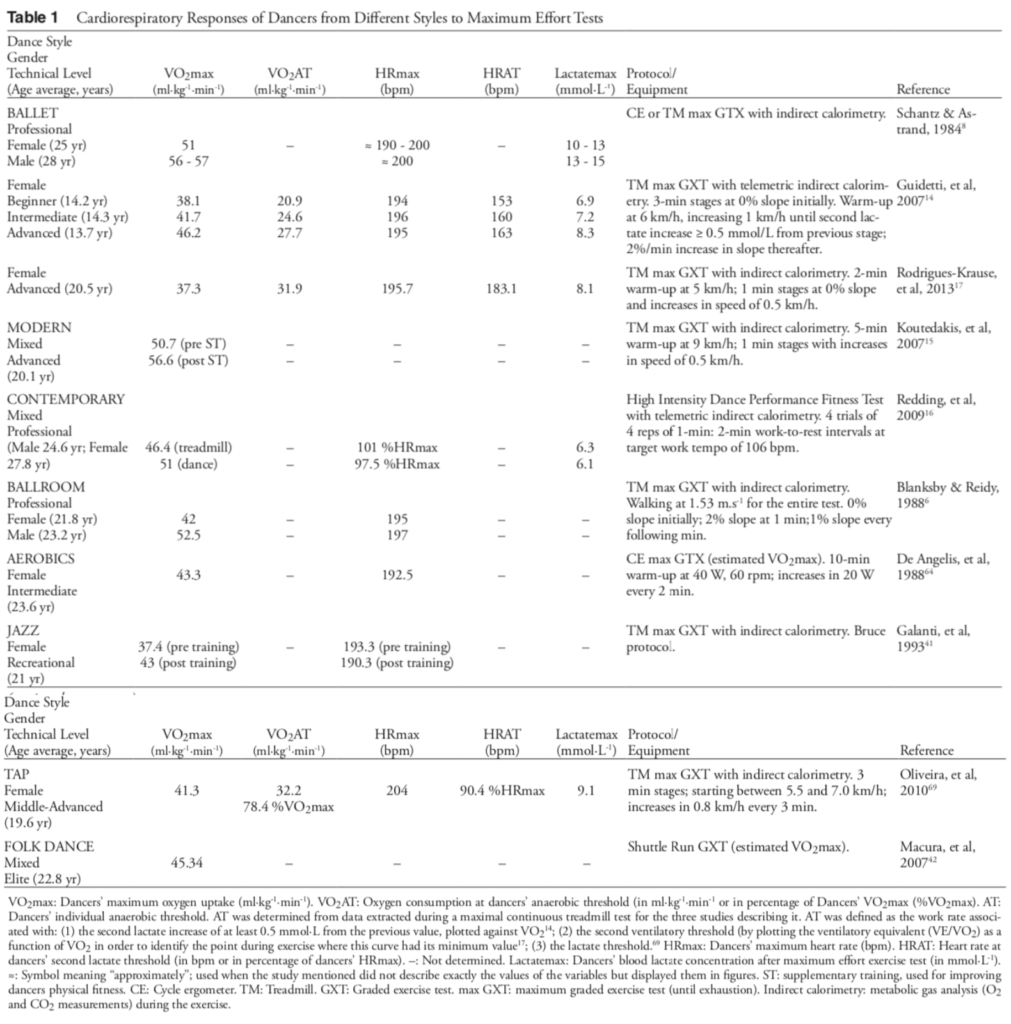

Several dance-specific tests exist to assess cardiovascular fitness. However, there is no standardized method for the different styles of dance. A standardized approach will match test-specific movements to style-specific techniques (i.e. there should be a standardized test for tap, which will be different than the standardized test for jazz, etc…).

Conclusion: Dance is a mixture of aerobic and anaerobic metabolic exercise. This mixture varies between styles of dance, age, gender, level of experience. There are also differences between energy expenditure in class, rehearsals or performance. Cross training with high intensity interval training may help develop a dancers aerobic capacity and muscular strength and will not interfere with the aesthetics of the human body. Fitness testing can measure aerobic and muscular strength which will help plan efficient exercise programs to supplement technical training. Strength training will help reduce the risk of injuries and enhance dance performance.