MMA, BJJ injuries

MMA, BJJ injuries

Mixed martial arts and their component practices, primarily striking and grappling (including boxing, Muay Thai, wrestling, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, Judo). Athletes are driven by the necessity to participate in tactical and technical training to develop a strong base and improve their skills. Multiple “training camps”, sometimes run by different coaches, can result in a poorly designed program when there is little communication amongst the athletes’ camp. Additionally, the competitor must juggle hours of sport specific drills (BJJ, Muaythai, wrestling) and a strength and conditioning program while allowing for adequate rest in between sessions. This potentially exposes the athlete to acute injuries as well as the potential for overtraining.

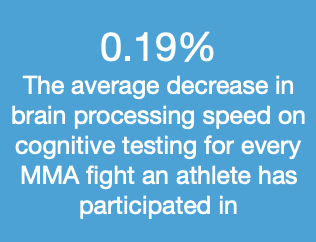

Injuries can occur during competition and training. Mixed martial arts competition injuries are sustained at an average of 26 injuries per 100 fight-participations (a fight-participation is a competitive event). About half are facial injuries, then injuries of the hand (13%), nose (10%) and eye (8%). The most frequent type of injury is skin lacerations (45%), followed by fractures (range of 7-43%) and concussions (3-20%). Injury rates are largely dependent on the specific type of training program. Grappling sports such as Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ), wrestling and Judo, have higher rates of joint injuries. These are predominantly of the elbow and knee for BJJ (64%); shoulder, elbow and knee for Judoka’s; shoulder (24%) and knee (17%) with wrestlers. Those with striking backgrounds including boxing, Muaythai and Tae-Kwon-Do (TKD), tend to have greater rates of injuries to the face and head including concussion, facial lacerations and fractures. If we were to take a closer look at striking sports it is apparent that boxers will often have more frequent injuries of the upper extremities whereas Muaythai or TKD are relatively more likely to have them of the lower extremities. Nearly 61% of karate and 42% of Muaythai injuries were of the head/neck region.

On the flip side, training accounts for the largest portion of athletes injuries. As mentioned before, the total volume and intensity spent during training exposes the athlete to a higher risk for injury. A combination of factors including poorly fitting or lack of equipment, fatigue, unnecessary aggressiveness when sparring and inadequate nutrition or fluid intake, all increase the athletes risk. Studies have demonstrated that anywhere from 80-90% of injuries are sustained during training and nearly 32% of these injuries will be recurring. You are four times more likely to be injured during training than you are while competing. If you have a fight coming up, how important would a well-designed program be to reduce your risk of injury? What are you risking when you’re name is pulled from a fight card due to an injury? A report by Michael Hutchinson on bloodyelbow.com titled “A look at the injury rates of major MMA fight camps (2009-2016)” demonstrates that some camps can lose up to 18% of their fighters to injury. This is not to say that no one went on after treatment to compete, but that they had to take off a considerable amount of time from training and earning a living due to something that may have been avoided. The numbers do not point fingers, faulting the coaches or management. It could be that certain types of fighters (coming from a specific background like wrestling or judo) gravitate to a particular school for whatever reason, and those fighters tend to be more injury prone for certain injuries. For example, someone with a strong wrestling background may have great take downs, but have a poor guard, increasing their risk of injury for muscle strains of the hips or legs to block an opponent from passing. Or a traditional stand-up boxer might have no idea how to sprawl or block certain shots, leading to knee or ankle injuries.