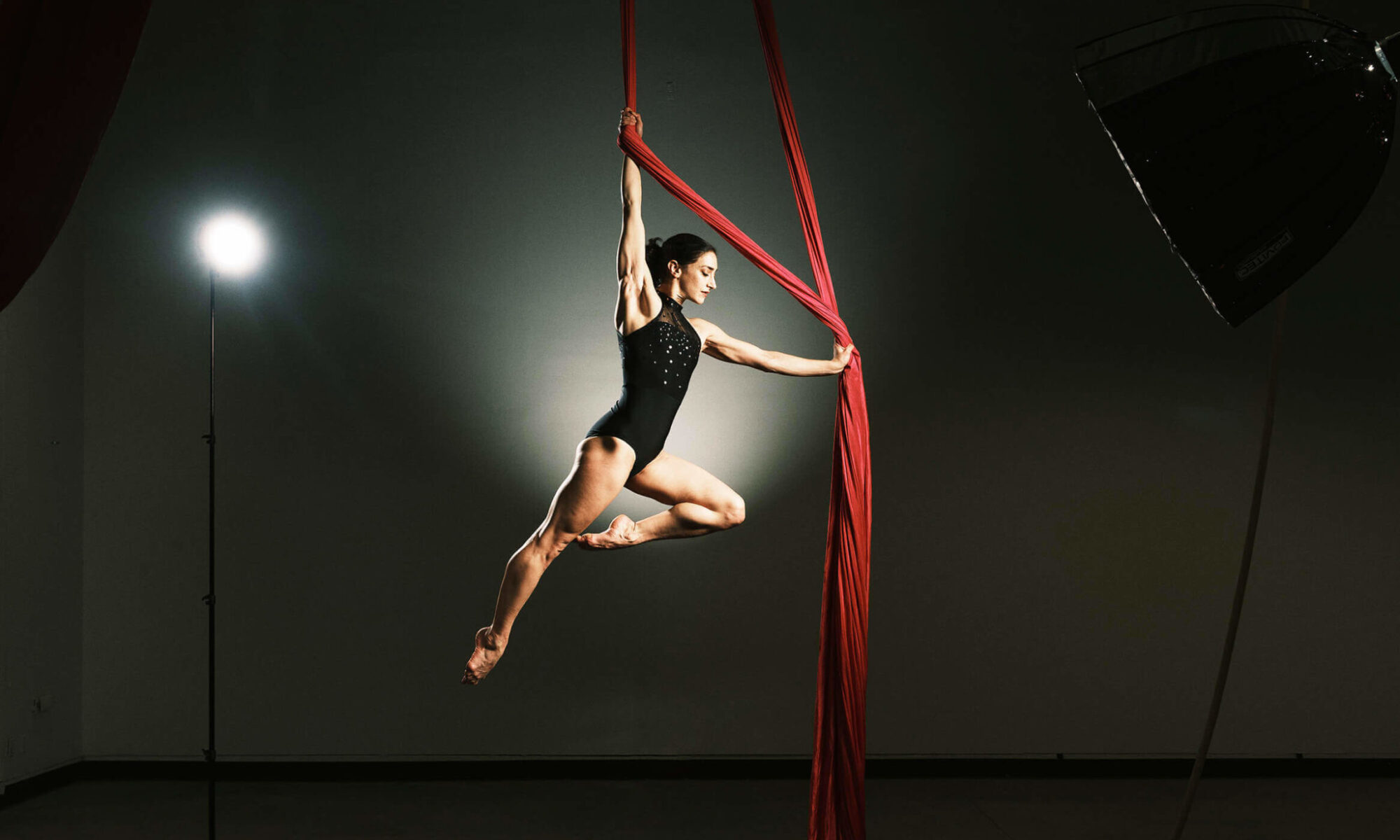

One of the things we need to establish is the definition of a “dancer”. It appears that dance can encompass a wide variety of styles (ballet, jazz, modern, break), avenues for performing (theatre, stage, cruises, or the street) and groups (university students, professional artists). Very often dancers engage in multiple forms of dance. This often makes dance research difficult to study. Ballet has been the most researched genre, with break dancing coming in second.

Different groups also have different definitions of what constitutes an “injury”. Does it mean you experience pain? Is it having to take time off and resting completely? Is it modifying all or part of a dance routine? Injuries can be influenced by a dancers prior experience of pain; communication with a choreographer, director, peers or family; current circumstances within the dance community such as employment or a scholarship at university.

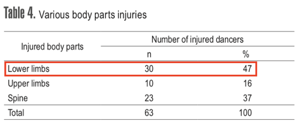

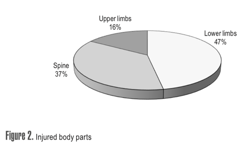

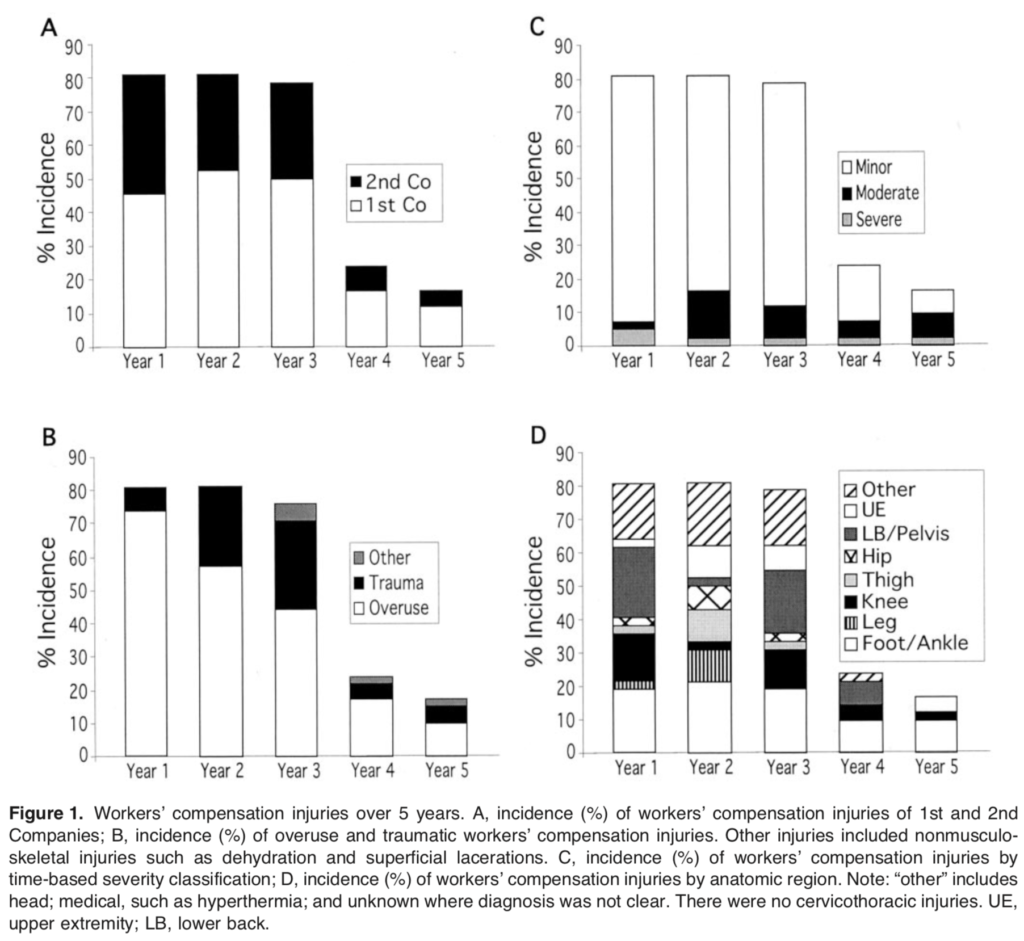

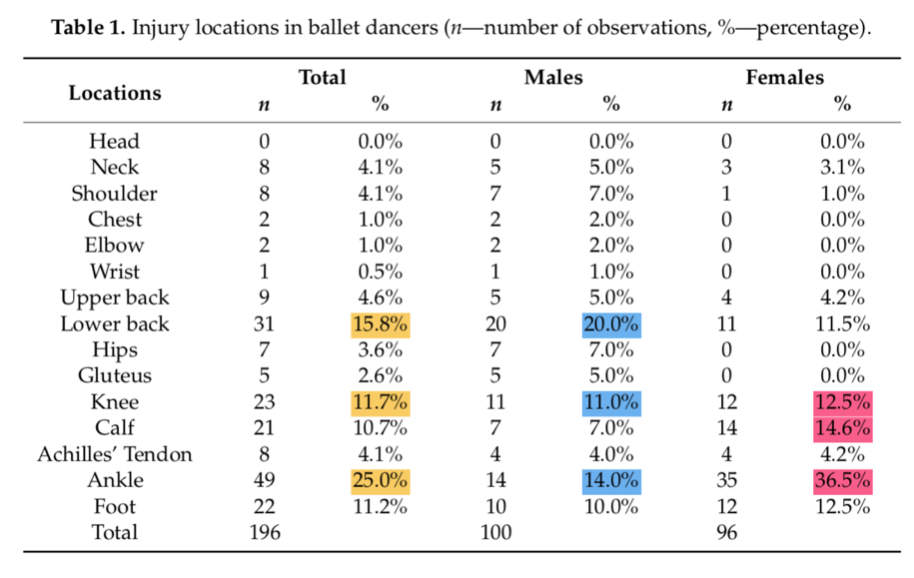

Across genres, a range of 42-97% of dancers were “injured”. This suggests that nearly all dancers will experience at least one injury in their career. The lower extremities (hips, knees and foot/ankle) were the most commonly reported to be injured. This is not surprising, given that dancers are required to perform leaps, floor work and wear different footwear. Footwear plays a greater role if multiple genres are required for a single contract (as is the case with performers on cruise ships).

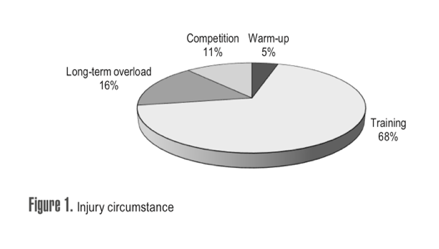

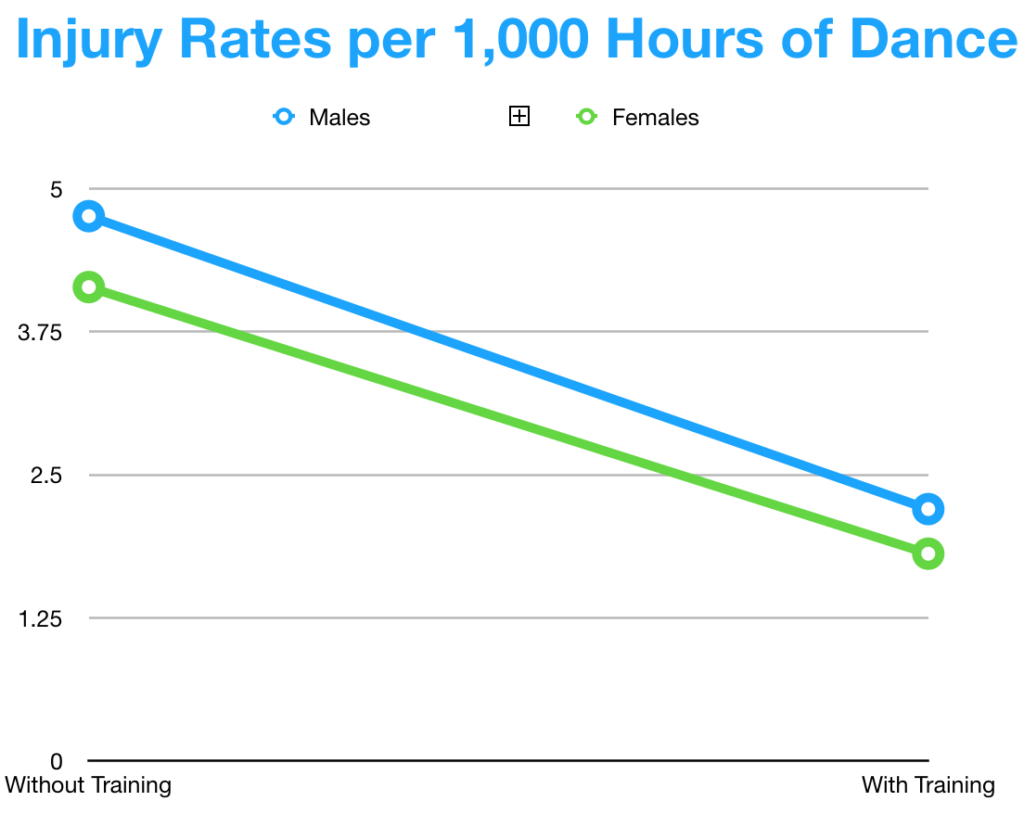

For every 1000 hours of dance, 4.4 injuries occurred. Overuse injuries were the most commonly reported. Females lost an average of 4 days, males an average of 9 days.

In conclusion, due to high injury rates and the near certainty that most, if not all, dancers will experience at least one injury in their career, an injury prevention program is warranted.

Dancers are a unique domain of athletes in that the pursuit of perfection in technique is multifaceted. Technique training and rehearsals comprise a large portion of a dancers time. This places a high volume of work on the athlete and creates a deep emotional connection to the performance itself. This means that dancers are often very emotionally invested. Understandably, suffering from an injury can invoke both physical and emotional pain.

Several studies demonstrate that dancers exhibit a higher pain threshold and higher pain tolerance. This means that they typically acknowledge pain when it is very high and tend to disregard the pain in order to continue to participate in dance. Ballet dancers have a difficult time distinguishing between “customary” dance pain and “pathological” pain. Coping skills (perception and reaction to pain) also tend to be poor in ballet dancers.

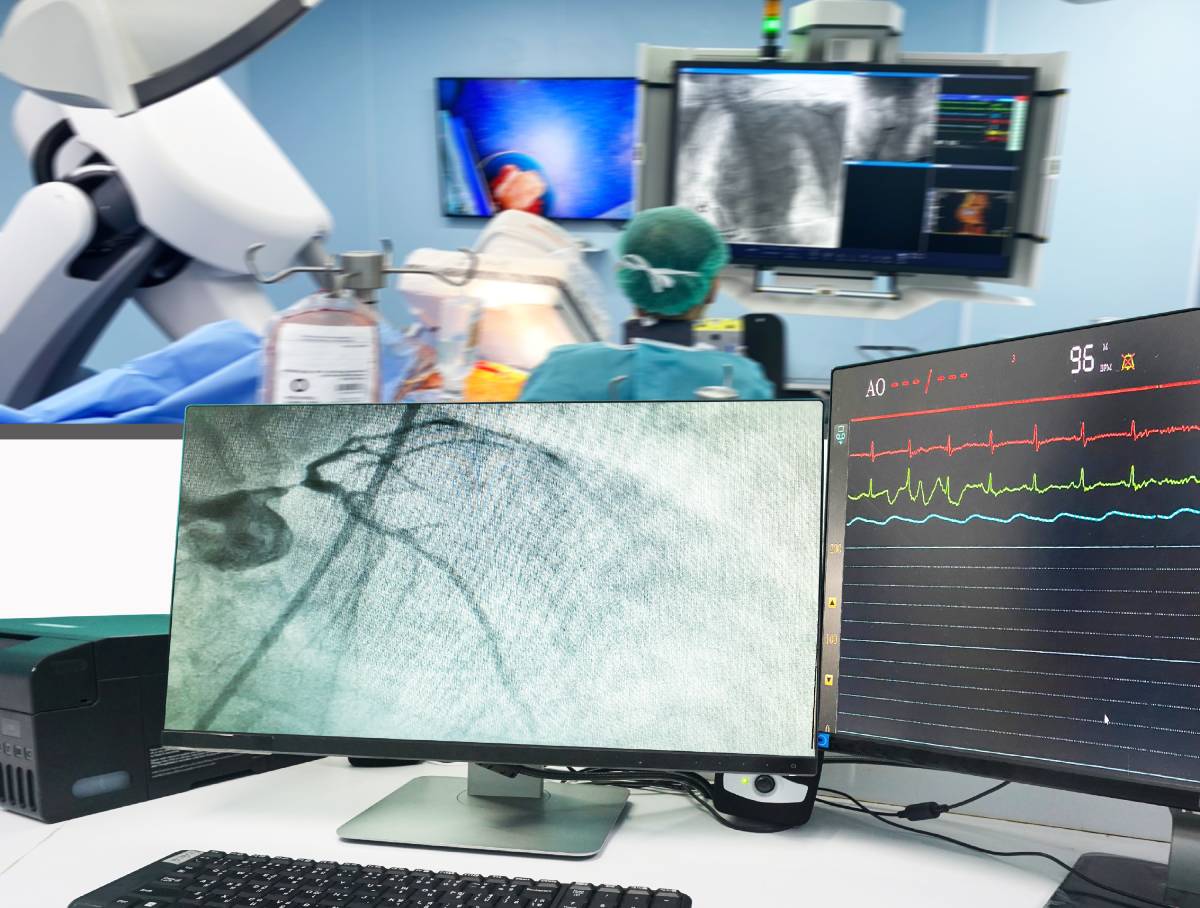

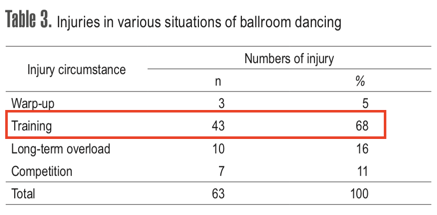

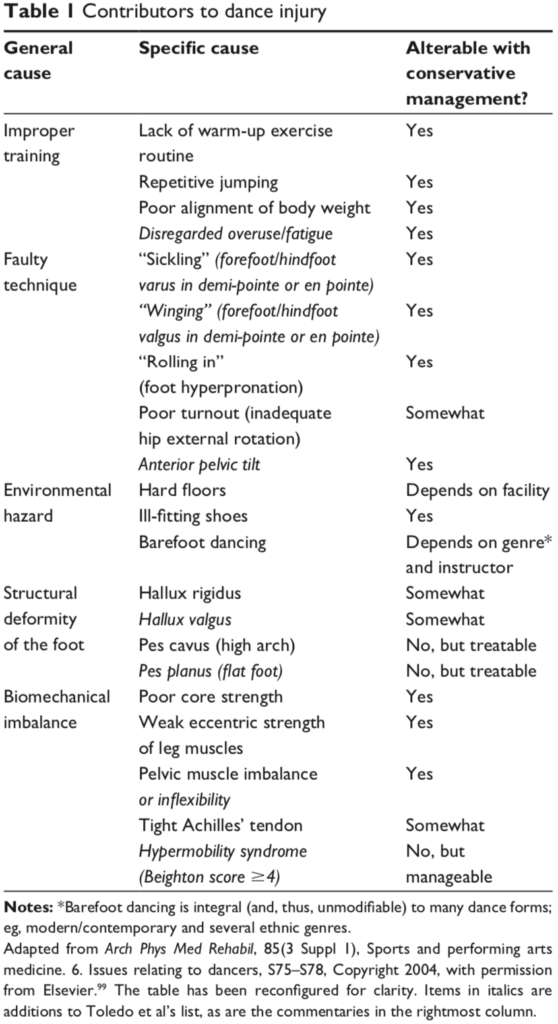

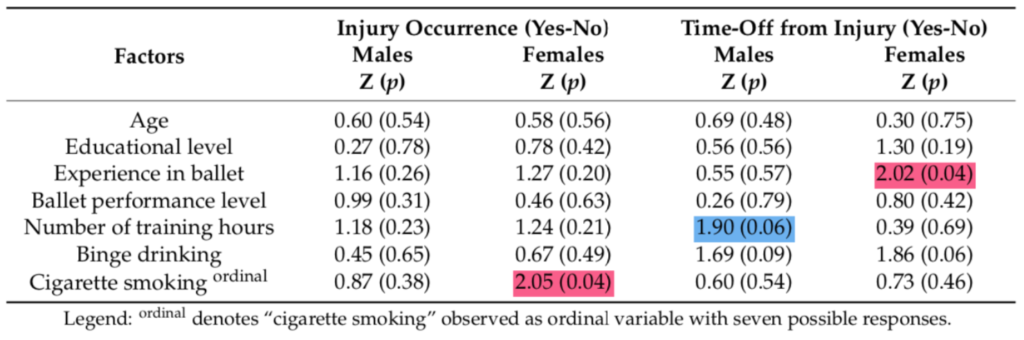

Several factors may contribute to dance injuries (see Table). Some of these factors are modifiable, meaning you have control over them. Communication with health care professionals also plays a role in a dancers understanding of their injury. A provider that understands the nature of dance, rehearsals and performing can provide the psychological support necessary for a dancer to feel comfortable sharing their pain experience. This often results in improved outcomes for the dancer.

Studies demonstrate that female dancers are more disciplined than male counterparts. Their more resilient outlook on dance performance often results in more success but consequentially greater risk of injury.

Poor training technique or coaching, especially with a skillset such as turnout, may increase the likelihood of a dancer suffering from back, hip, knee and/or foot and ankle pain. Younger dancers are more susceptible because dance technique is a requisite for an aesthetically pleasing performance.