Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) is more than just feeling blue & wanting to take a day off. It is a sort of all-encompassing entity that blurs your vision (metaphorically speaking, if you have blurry vision you should get that checked out) and can take muuuuuuch longer to recover.

Before we dive into OTS, lets talk about your training schedule.

When training, whether that is rehearsing or exercising, there are a few things that need to be accounted for.

This usually includes the FITT principles

Frequency: how often you train (body part, days of the week/month/year)

Intensity: how much effort are you putting into the training

Time: how much time per session, measured over a day to weeks

Type: are you performing power training? Super slow training? Cardio?

What are you doing in rehearsals? Lounging around or non-stop partner work?

Write some of these elements in your calendar. Next to that write how you are generally feeling: full energy throughout the day, unstoppable, lethargic, irritable etc…

Get a general idea of how much work you’re putting in and how your body responds to that specific training. Cookie-cutter programs are garbage. Everyone starts at a different level of exercise capacity & everyone responds differently to exercise. There is no “one-size-fits-all” program. Yes, most people may respond to HIIT fairly well, but there will always be outliers.

Anywho…

If you notice that you are under the weather (but not physically sick)- you don’t feel like you’re getting as much out of your workout as before, you’re strength/cardio isn’t improving or maybe your just want to sit in bed and eat pizza and donuts- every day of the week, then you might be edging towards overtraining.

While there is not specific blood or psychological test that says “Yep! You have the overtraining syndrome”, there are general markers of individual emotional & physical states that suggest you might need some (modified) time off.

Lets take a look at some “triggers”:

-Increased training load without recovery

-Monotony of training

-Excessive number of competitions

-Sleep disturbances

-Stressors including personal life (family, relationships) and occupation

-Previous illness

-Altitude exposure

-Heat injury episode

-Severe “bonk”

As you can see, severe “bonk”-ing is not exactly PhD material. But you get the idea…

Symptoms may include:

-Fatigue

-Depression

-Bradycardia/tachycardia (abnormally slow/fast heart rate)

-Loss of motivation

-Insomnia

-Irritability

-Agitation/anxiety

-Hypertension

-Restlessness

-Anorexia

-Weight loss

-Poor of mental concentration

-Heavy/sore/stiff muscles

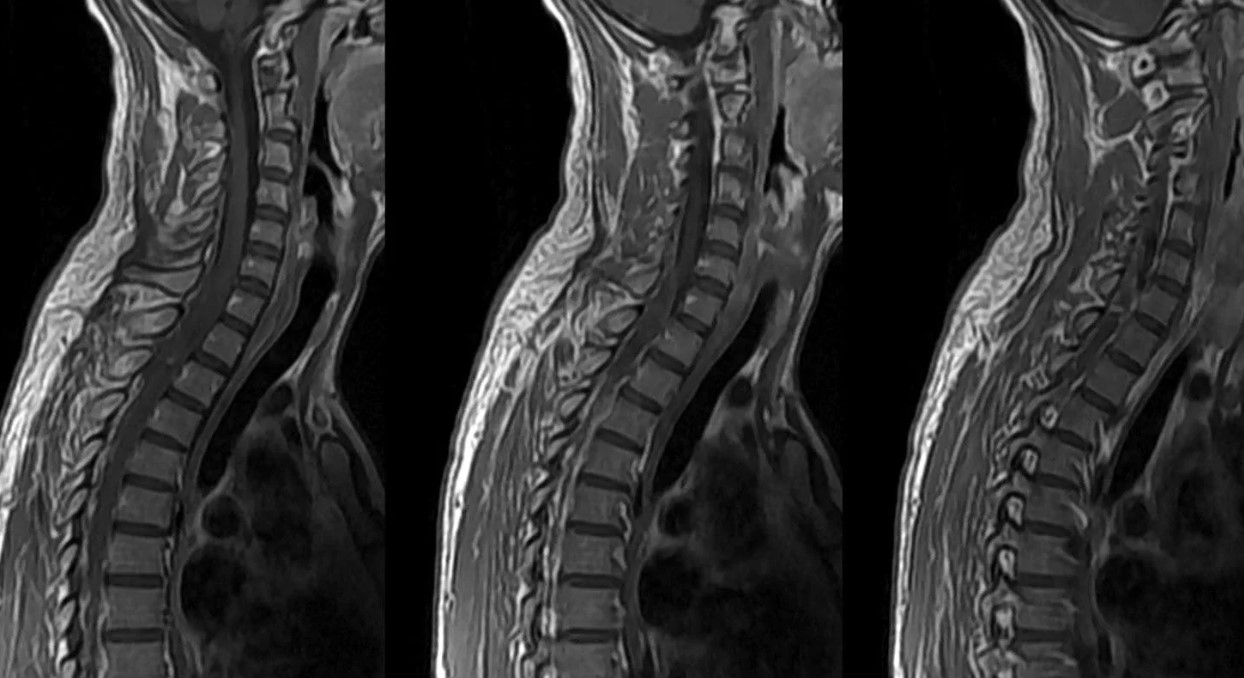

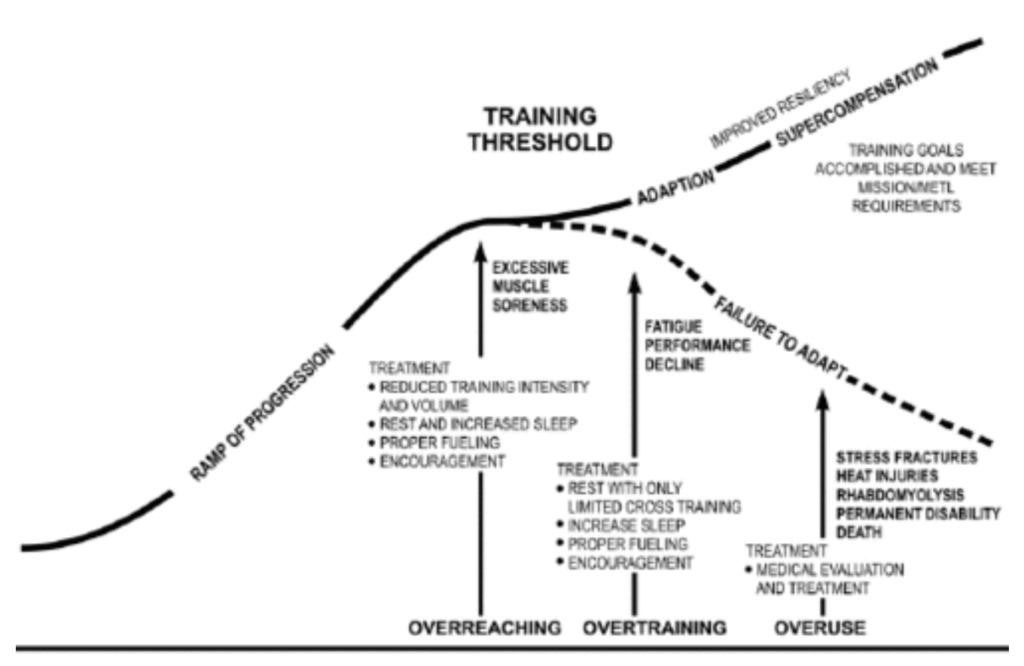

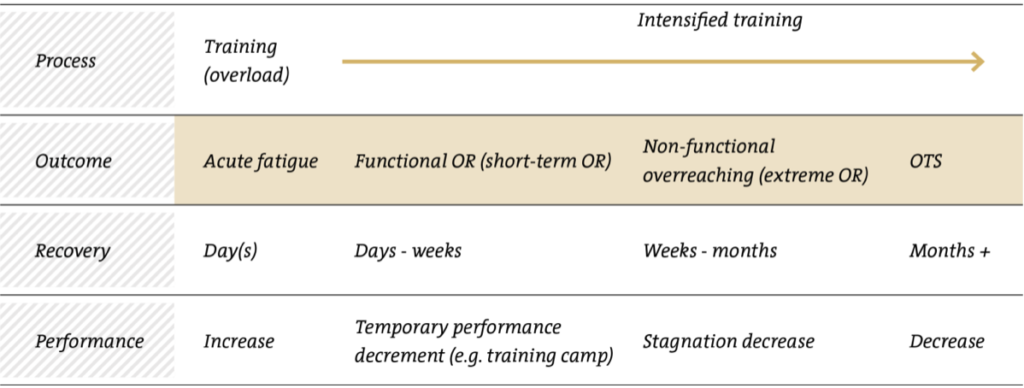

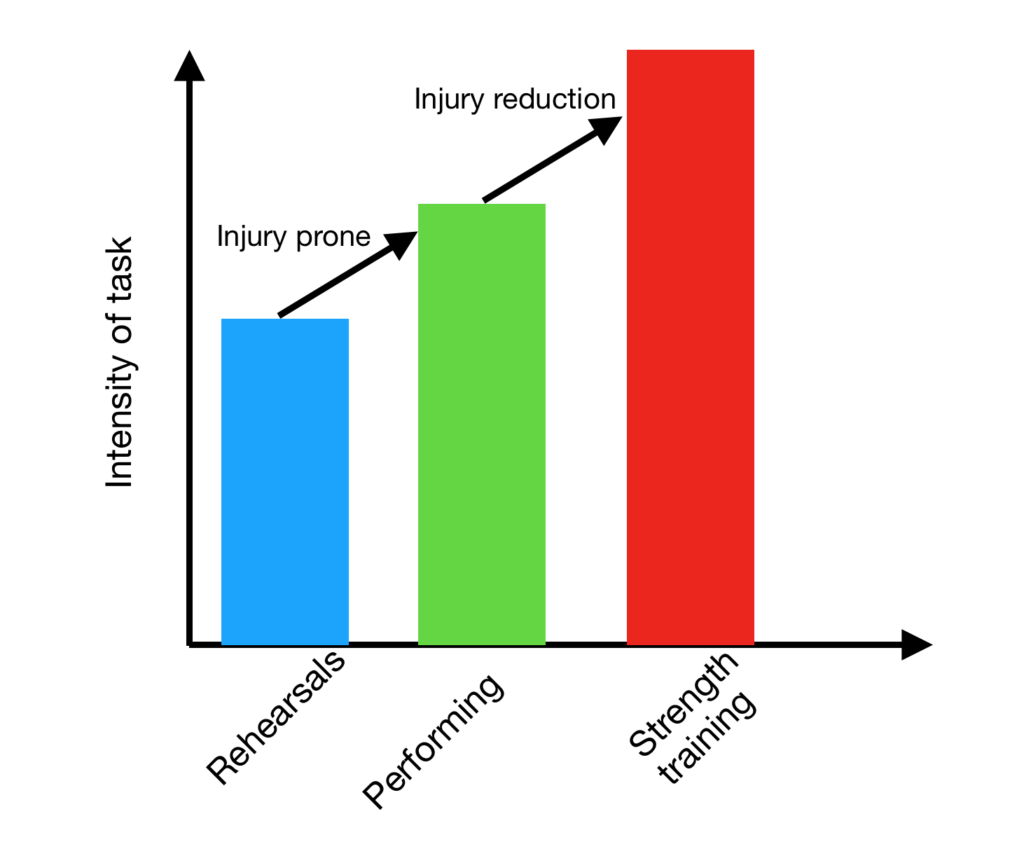

This fuzzy picture demonstrates what we in the science community attribute to “training threshold”. Generally speaking, over the course of your phenomenal career, you should be getting better. Stronger muscles, more flexible joints, better technique etc…