Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

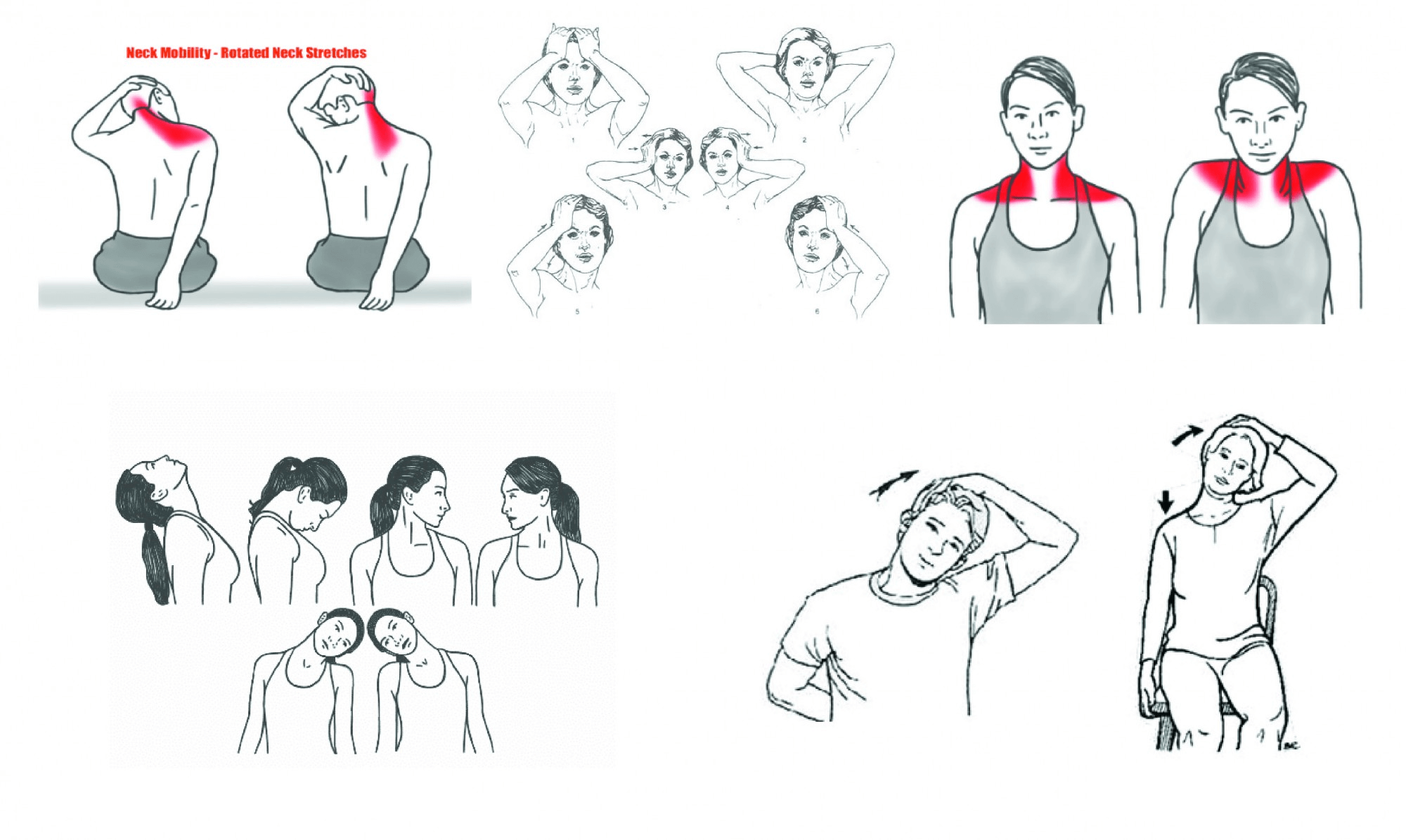

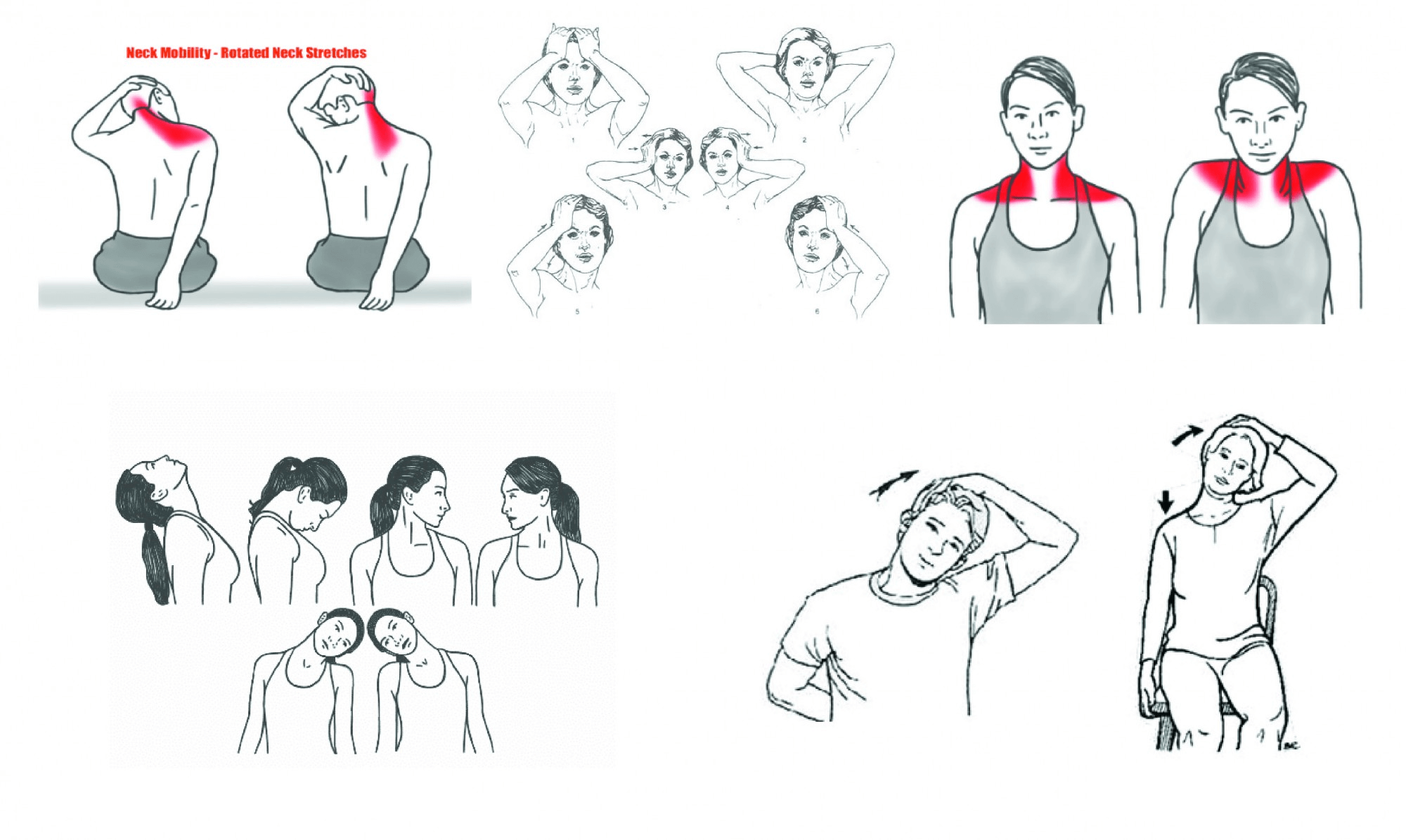

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

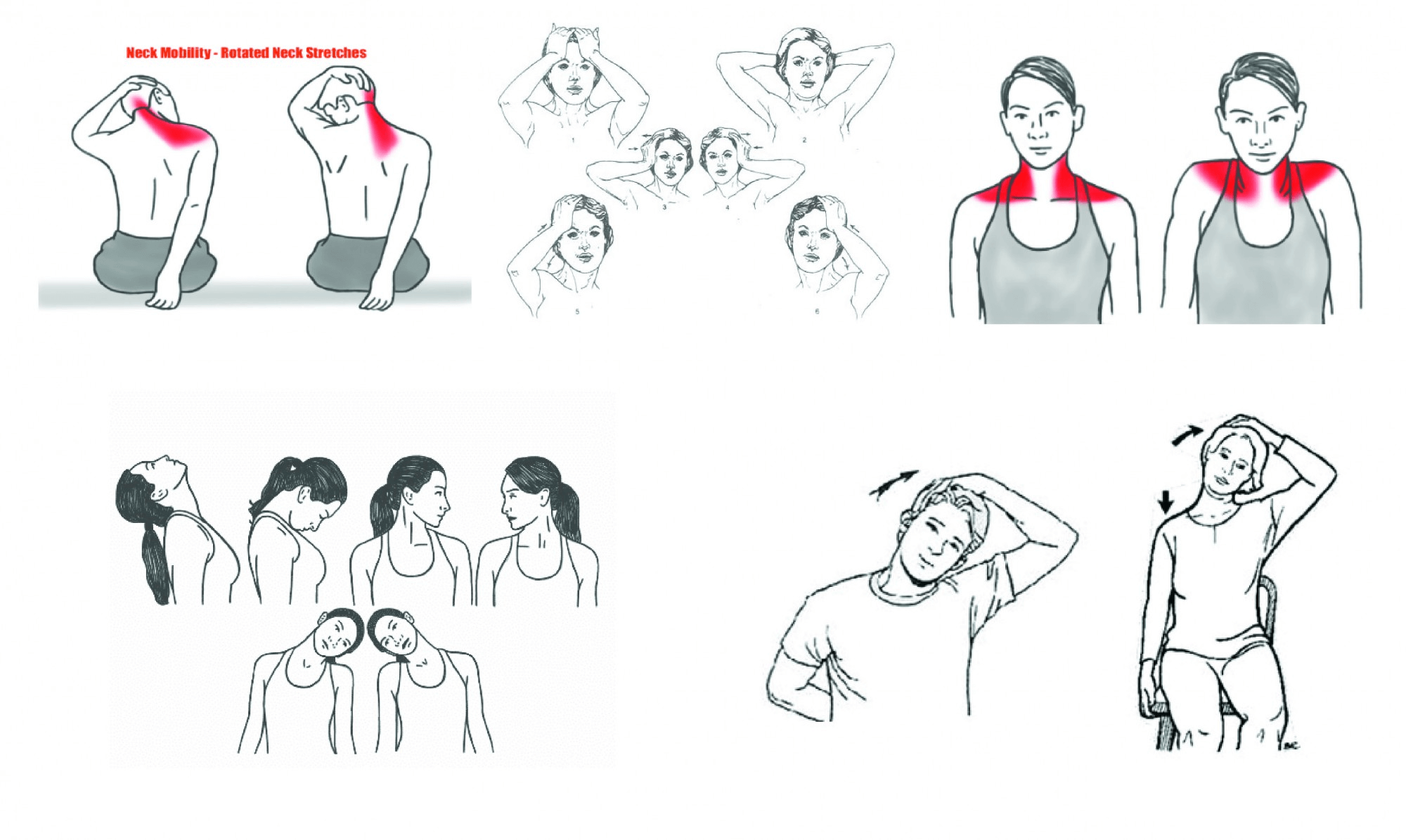

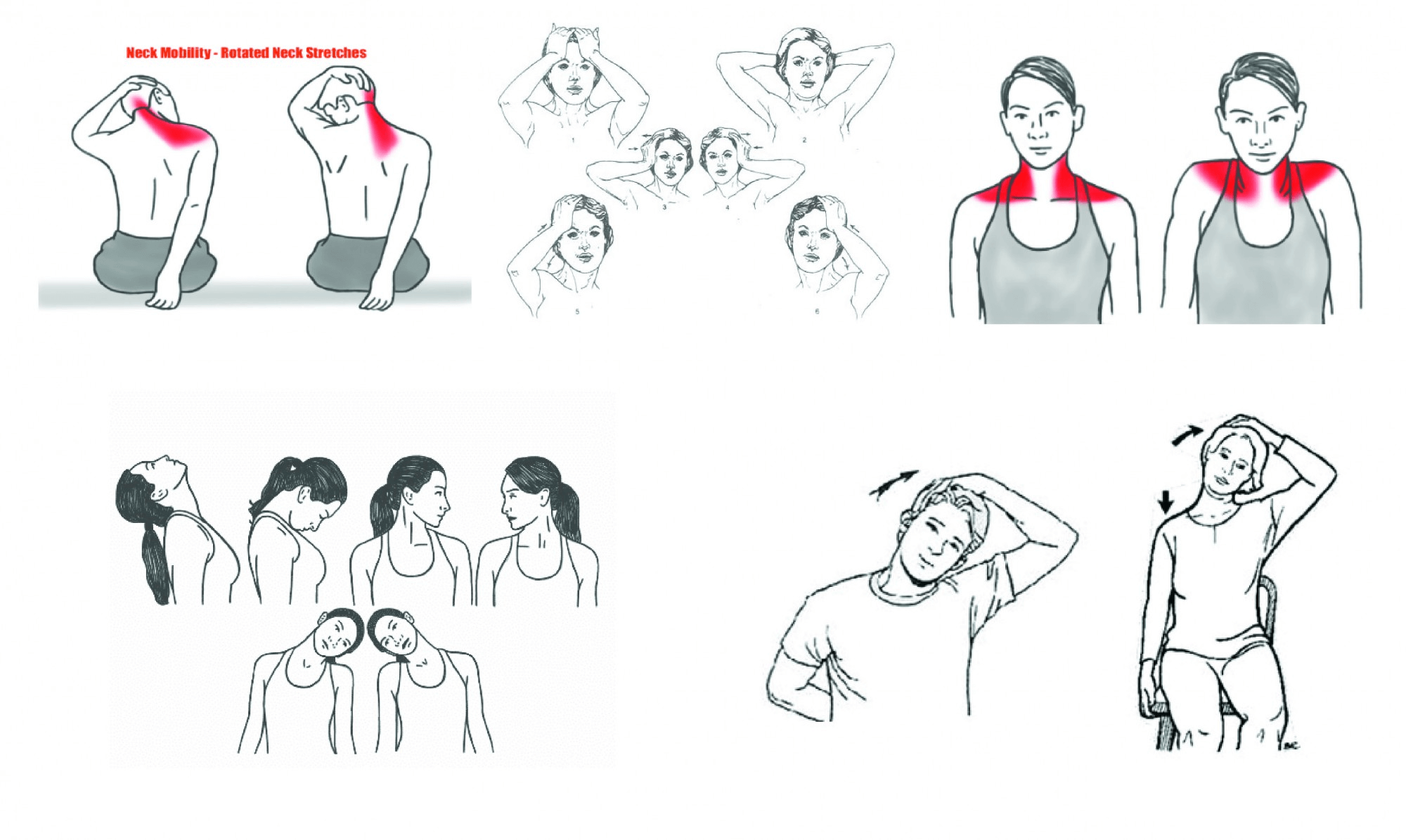

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Like all other skeletal muscles in the body, neck muscles contain lots of tiny, elastic fibers that allow the muscles to contract. Sheaths of tough connective tissue hold the fibers together. Skeletal muscle fibers are red and white, so the muscles look striated (striped or streaked).

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

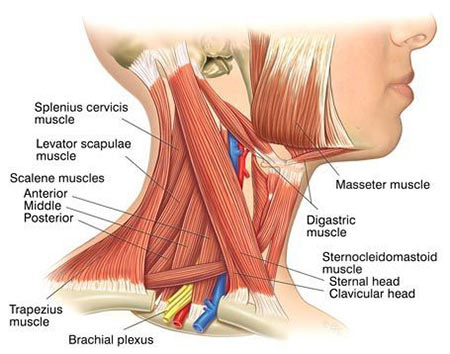

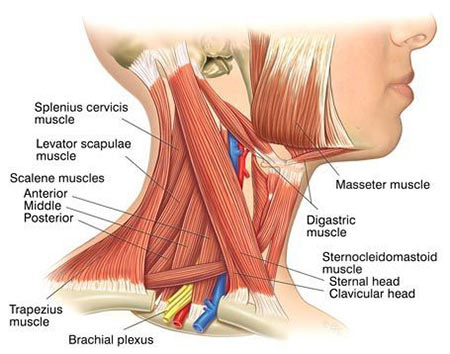

Posterior neck muscles include:

Like all other skeletal muscles in the body, neck muscles contain lots of tiny, elastic fibers that allow the muscles to contract. Sheaths of tough connective tissue hold the fibers together. Skeletal muscle fibers are red and white, so the muscles look striated (striped or streaked).

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Posterior neck muscles include:

Like all other skeletal muscles in the body, neck muscles contain lots of tiny, elastic fibers that allow the muscles to contract. Sheaths of tough connective tissue hold the fibers together. Skeletal muscle fibers are red and white, so the muscles look striated (striped or streaked).

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

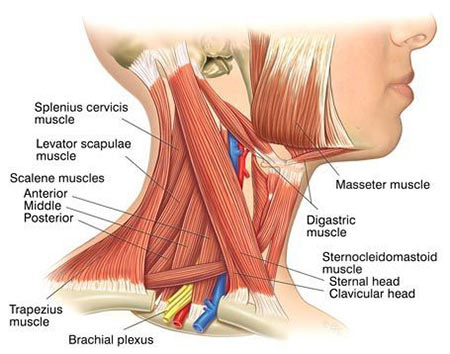

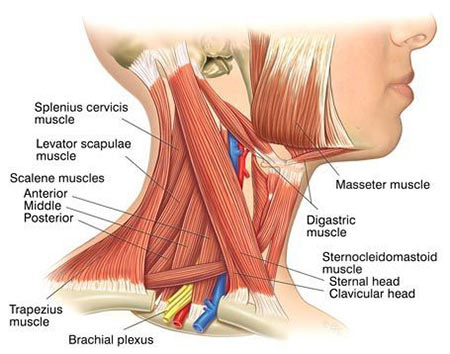

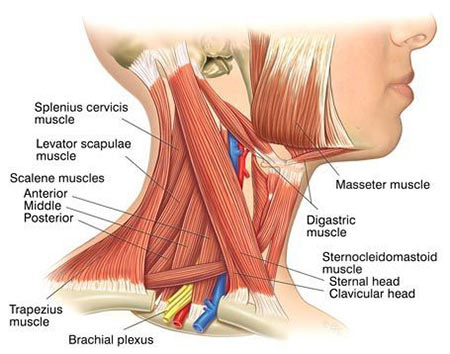

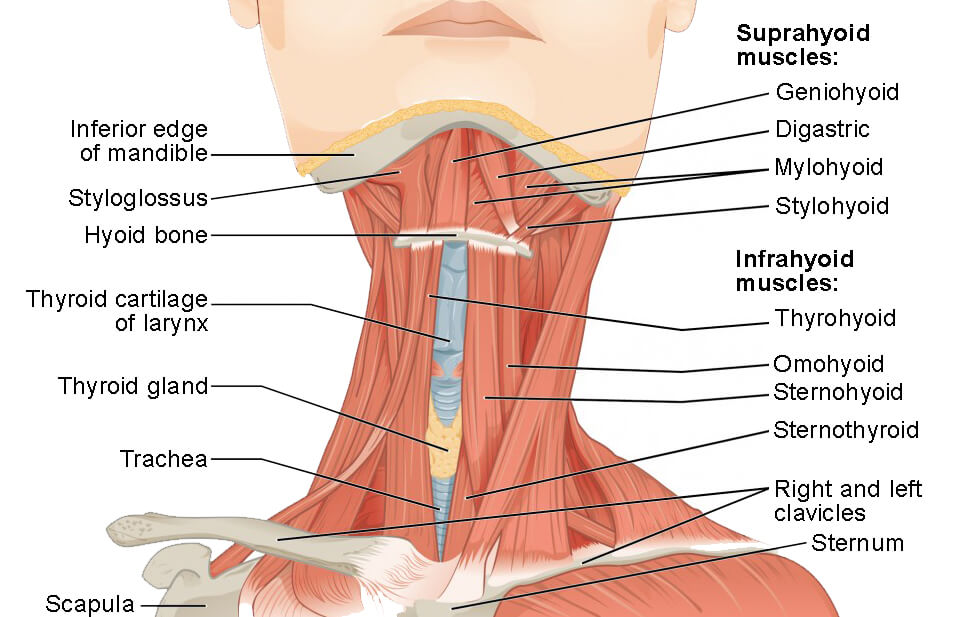

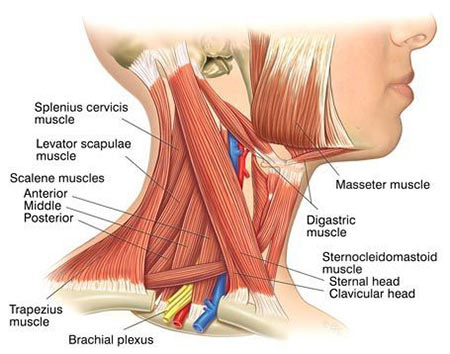

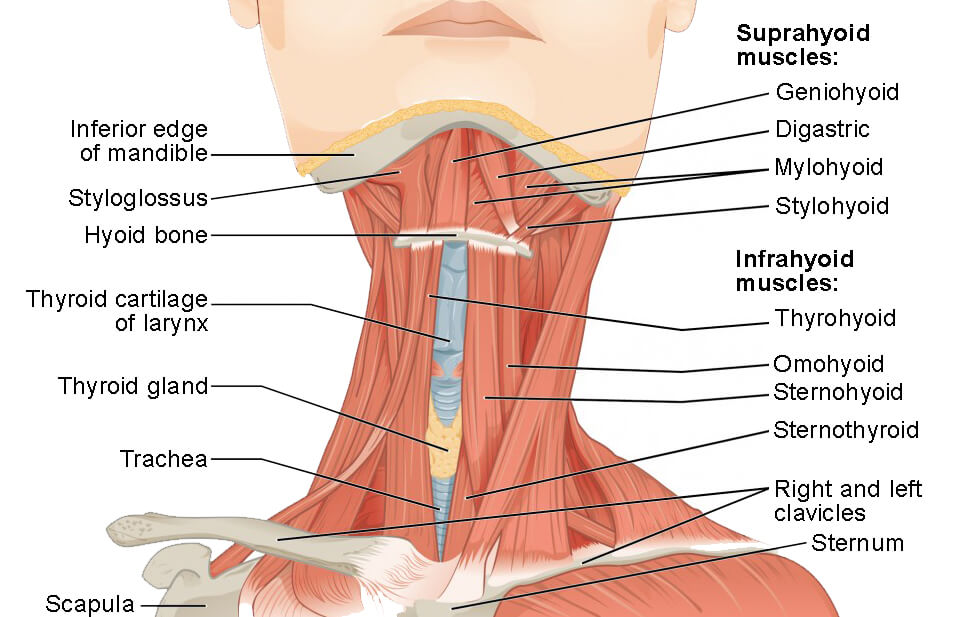

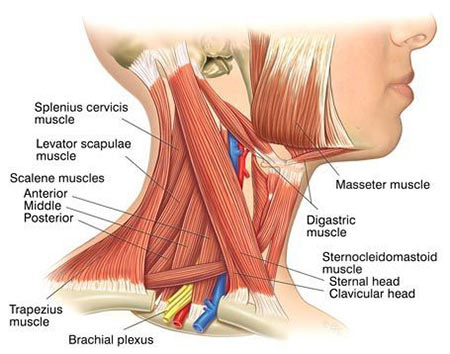

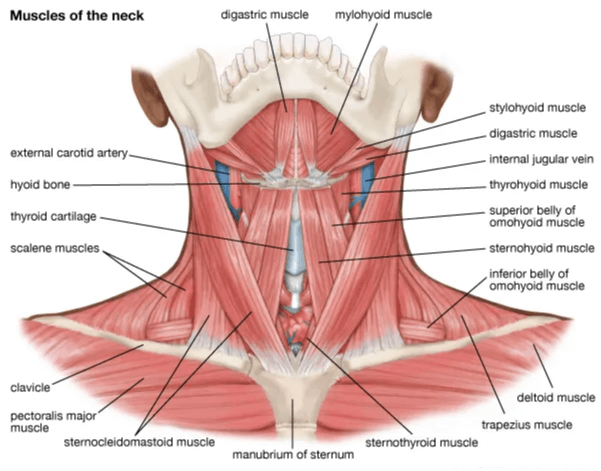

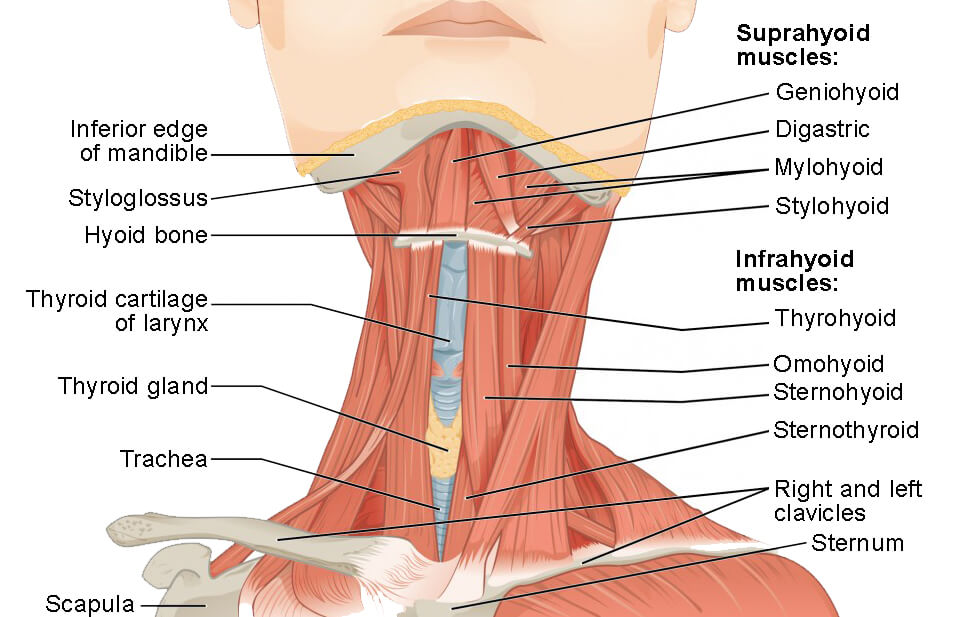

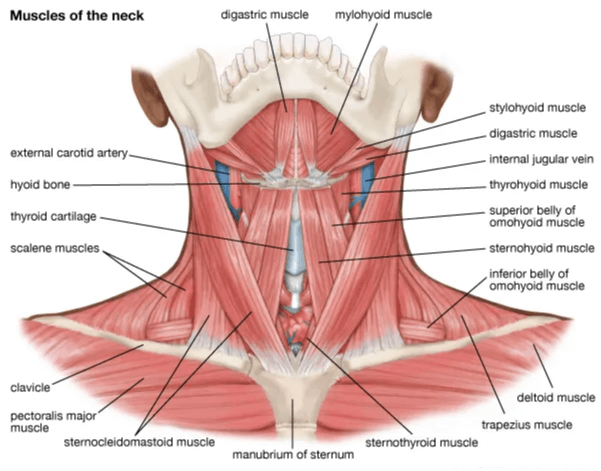

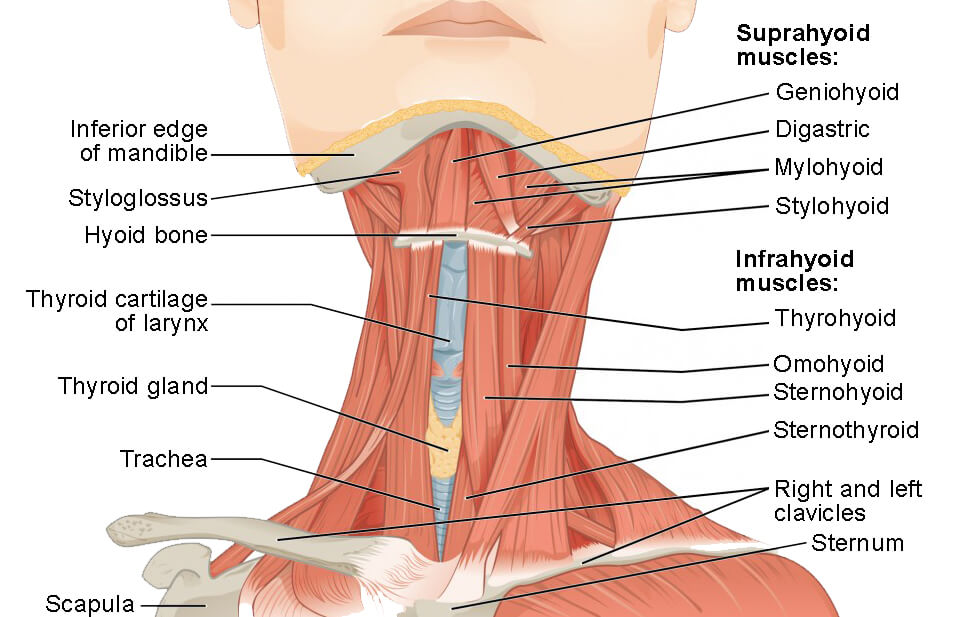

There are three types of neck muscles: anterior (front), posterior (back) and lateral (side) muscles.

Anterior neck muscles include:

Posterior neck muscles include:

Like all other skeletal muscles in the body, neck muscles contain lots of tiny, elastic fibers that allow the muscles to contract. Sheaths of tough connective tissue hold the fibers together. Skeletal muscle fibers are red and white, so the muscles look striated (striped or streaked).

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

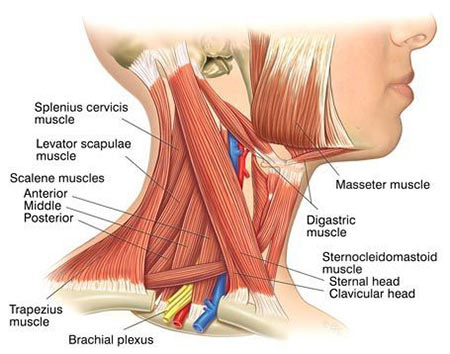

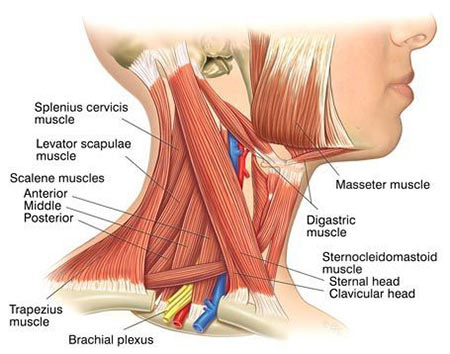

Your neck muscles are at the front, back and sides of your neck. From the back, they begin just beneath the base of your skull and extend down near the middle of your back, around your shoulder blades. From the front, these muscles begin at your jaw and extend to your collarbone at the top of your chest.

There are three types of neck muscles: anterior (front), posterior (back) and lateral (side) muscles.

Anterior neck muscles include:

Posterior neck muscles include:

Like all other skeletal muscles in the body, neck muscles contain lots of tiny, elastic fibers that allow the muscles to contract. Sheaths of tough connective tissue hold the fibers together. Skeletal muscle fibers are red and white, so the muscles look striated (striped or streaked).

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

The neck muscles serve a variety of functions, including:

Your neck muscles are at the front, back and sides of your neck. From the back, they begin just beneath the base of your skull and extend down near the middle of your back, around your shoulder blades. From the front, these muscles begin at your jaw and extend to your collarbone at the top of your chest.

There are three types of neck muscles: anterior (front), posterior (back) and lateral (side) muscles.

Anterior neck muscles include:

Posterior neck muscles include:

Like all other skeletal muscles in the body, neck muscles contain lots of tiny, elastic fibers that allow the muscles to contract. Sheaths of tough connective tissue hold the fibers together. Skeletal muscle fibers are red and white, so the muscles look striated (striped or streaked).

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

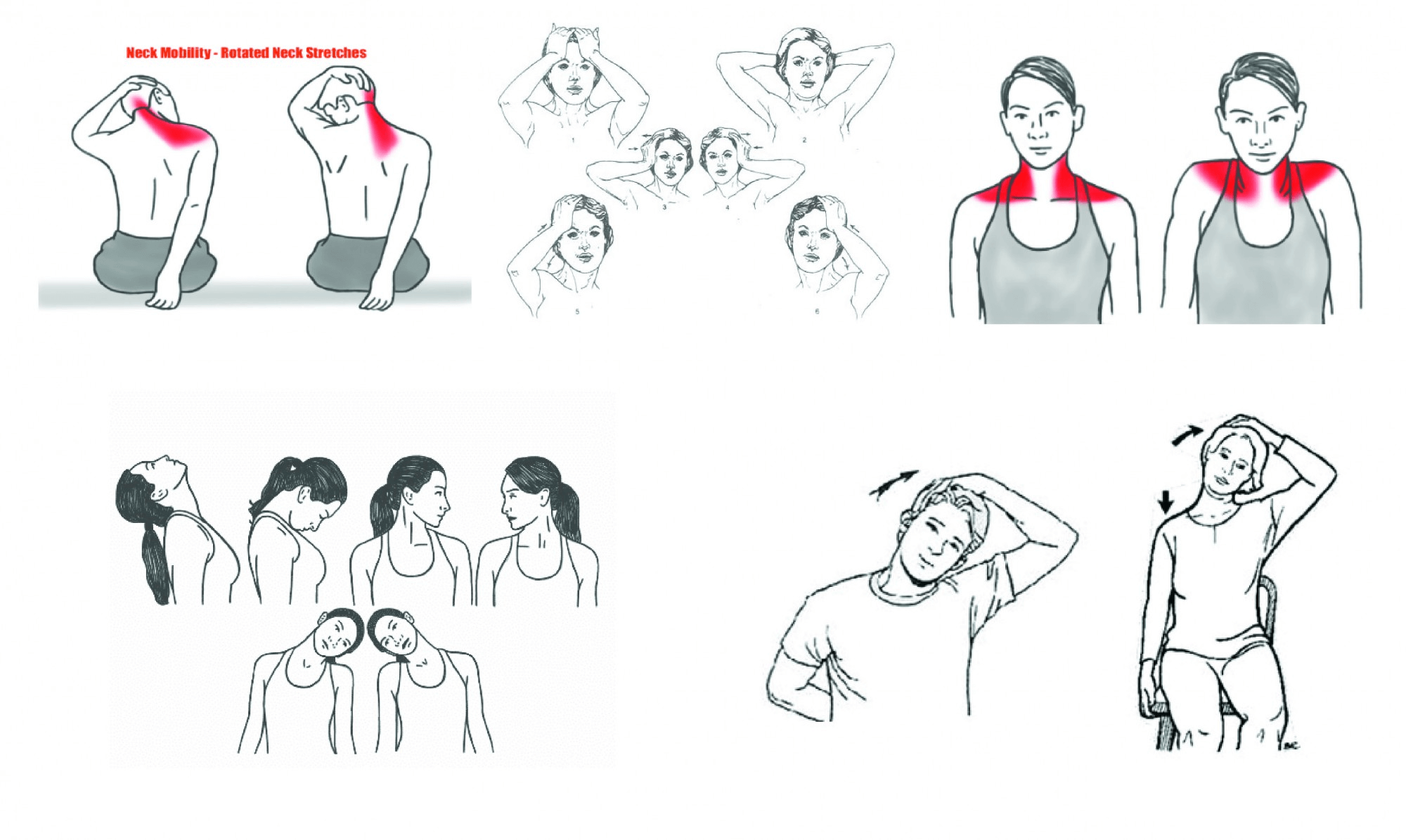

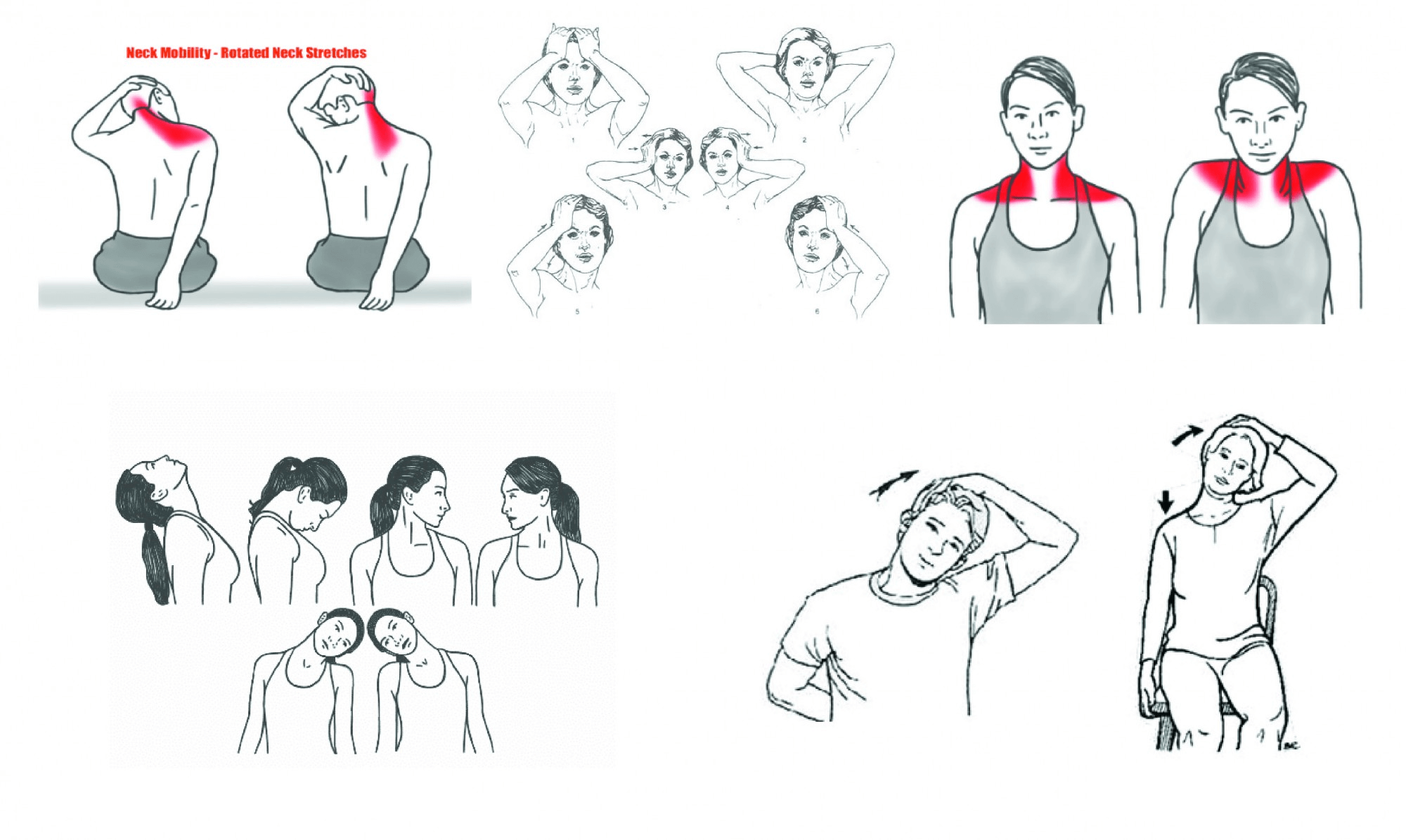

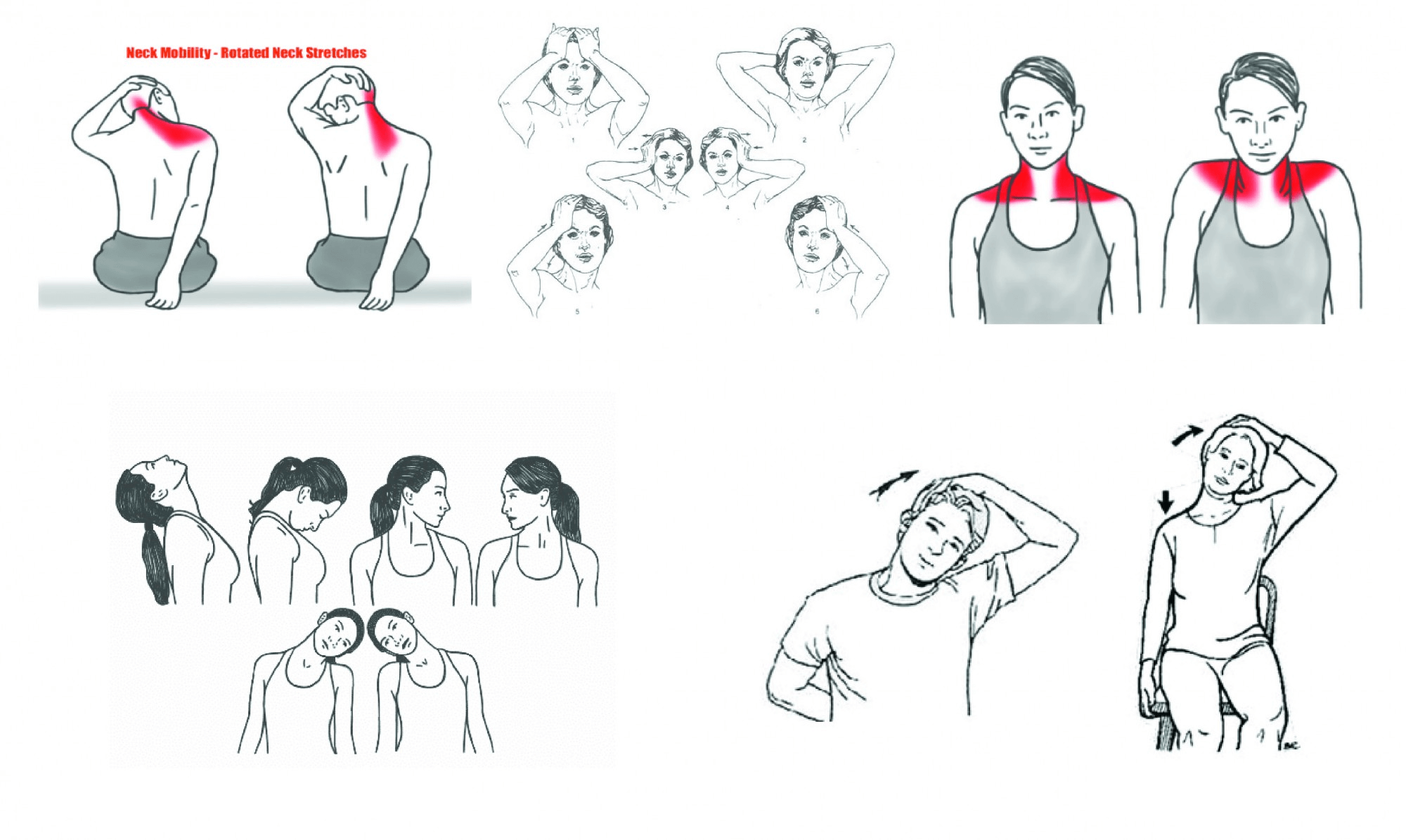

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Your neck muscles are part of a complex musculoskeletal system (soft tissues and bones) that connect the base of your skull to your torso. Muscles contain fibers that contract (get smaller), allowing you to perform lots of different movements. Your neck muscles help you do everything from chewing and swallowing to nodding your head. You have more than 20 neck muscles.

The muscles in your neck are skeletal muscles, meaning they’re attached to bones by tendons. They’re voluntary muscles, so you control how they move and work. Other types of muscles in the body – cardiac (in the heart) and smooth (in hollow organs like your stomach) – are involuntary, which means they work without you having to think about it.

The neck muscles serve a variety of functions, including:

Your neck muscles are at the front, back and sides of your neck. From the back, they begin just beneath the base of your skull and extend down near the middle of your back, around your shoulder blades. From the front, these muscles begin at your jaw and extend to your collarbone at the top of your chest.

There are three types of neck muscles: anterior (front), posterior (back) and lateral (side) muscles.

Anterior neck muscles include:

Posterior neck muscles include:

Like all other skeletal muscles in the body, neck muscles contain lots of tiny, elastic fibers that allow the muscles to contract. Sheaths of tough connective tissue hold the fibers together. Skeletal muscle fibers are red and white, so the muscles look striated (striped or streaked).

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

You have more than 20 neck muscles, extending from the base of your skull and jaw down to your shoulder blades and collarbone. These muscles support and stabilize your head, neck and the upper part of your spine. They help you move your head in different directions and assist with chewing, swallowing and breathing.

Your neck muscles are part of a complex musculoskeletal system (soft tissues and bones) that connect the base of your skull to your torso. Muscles contain fibers that contract (get smaller), allowing you to perform lots of different movements. Your neck muscles help you do everything from chewing and swallowing to nodding your head. You have more than 20 neck muscles.

The muscles in your neck are skeletal muscles, meaning they’re attached to bones by tendons. They’re voluntary muscles, so you control how they move and work. Other types of muscles in the body – cardiac (in the heart) and smooth (in hollow organs like your stomach) – are involuntary, which means they work without you having to think about it.

The neck muscles serve a variety of functions, including:

Your neck muscles are at the front, back and sides of your neck. From the back, they begin just beneath the base of your skull and extend down near the middle of your back, around your shoulder blades. From the front, these muscles begin at your jaw and extend to your collarbone at the top of your chest.

There are three types of neck muscles: anterior (front), posterior (back) and lateral (side) muscles.

Anterior neck muscles include:

Posterior neck muscles include:

Like all other skeletal muscles in the body, neck muscles contain lots of tiny, elastic fibers that allow the muscles to contract. Sheaths of tough connective tissue hold the fibers together. Skeletal muscle fibers are red and white, so the muscles look striated (striped or streaked).

Common conditions that affect the neck muscles include:

Studies estimate that about 14% of the population has some form of chronic neck pain. Approximately 45% of those cases (about 15.5 million Americans) may be due to whiplash.

Whiplash is typically the result of an automobile accident if you’re rear-ended. Neck injuries such as strains are common in athletes who play collision sports like football or hockey. But neck pain can happen to anyone. Turning your head suddenly, sleeping on your neck at an awkward angle, sitting at your desk with bad posture or other everyday activities can cause the occasional neck kink.

Neck injuries may cause:

Your healthcare provider reviews your symptoms and performs a physical exam. They may ask you to move your head, neck and shoulders in different directions to check your muscle strength and range of motion. Your provider may recommend imaging exams, such as an ultrasound or CT scan, if they think you may have muscle damage.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Keep your neck muscles strong and healthy by:

Serious neck injuries need immediate medical attention. Contact your doctor right away if you have:

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

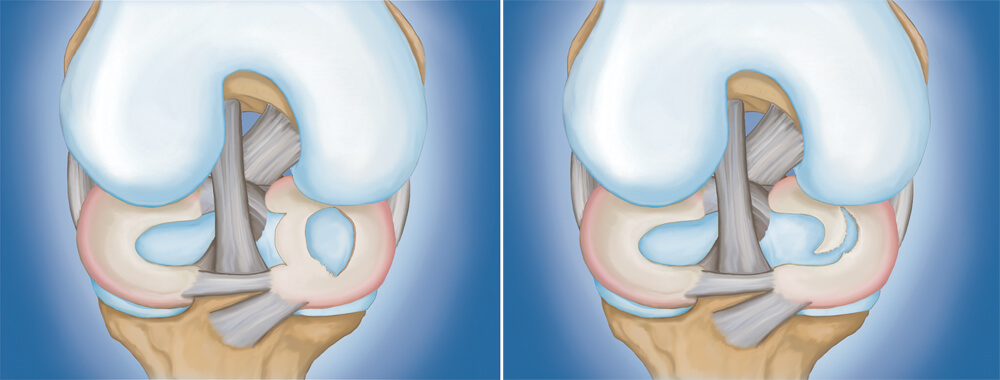

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

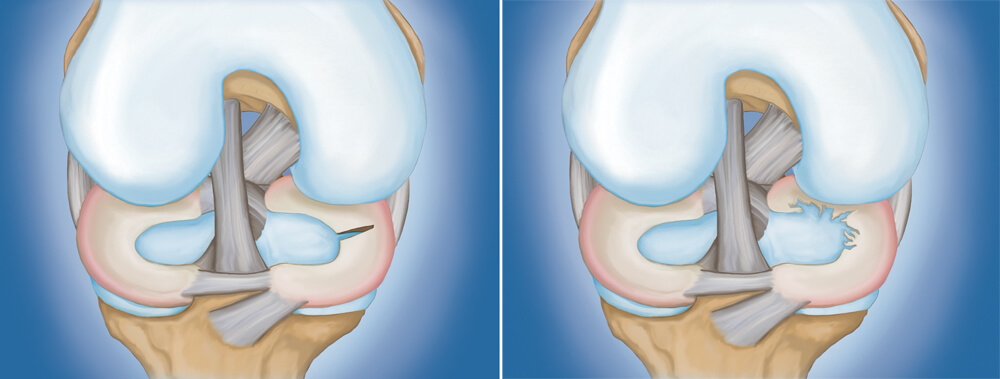

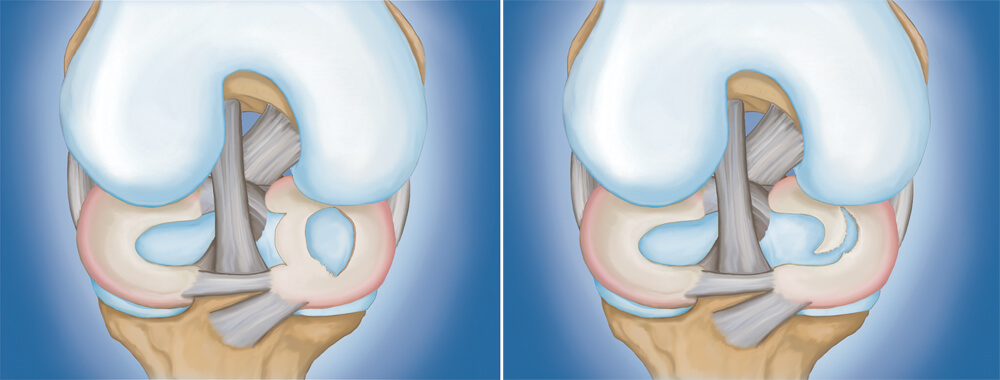

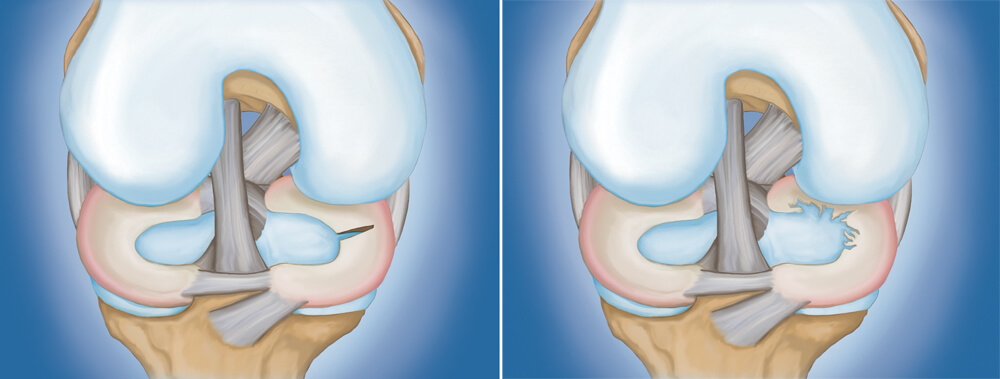

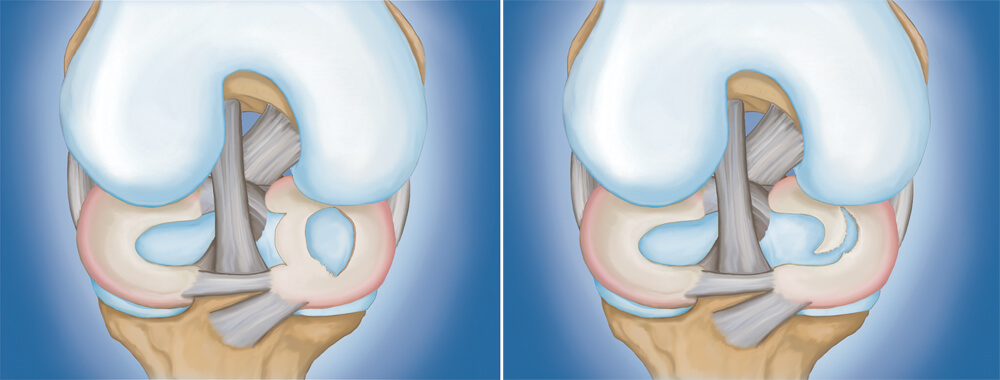

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

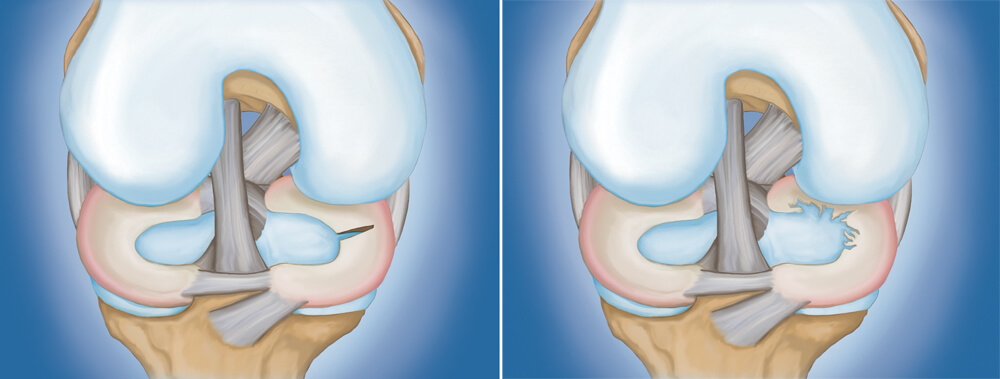

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

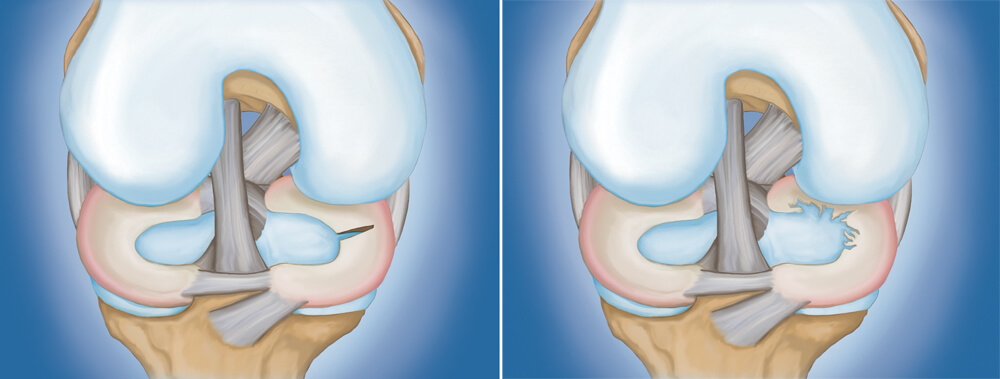

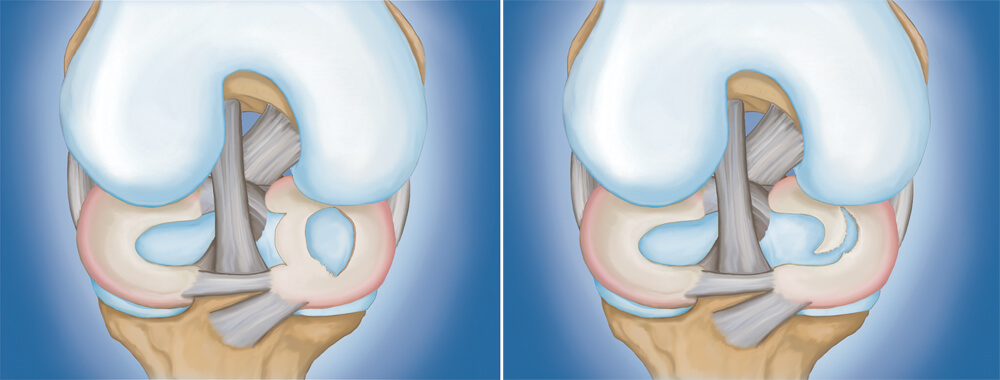

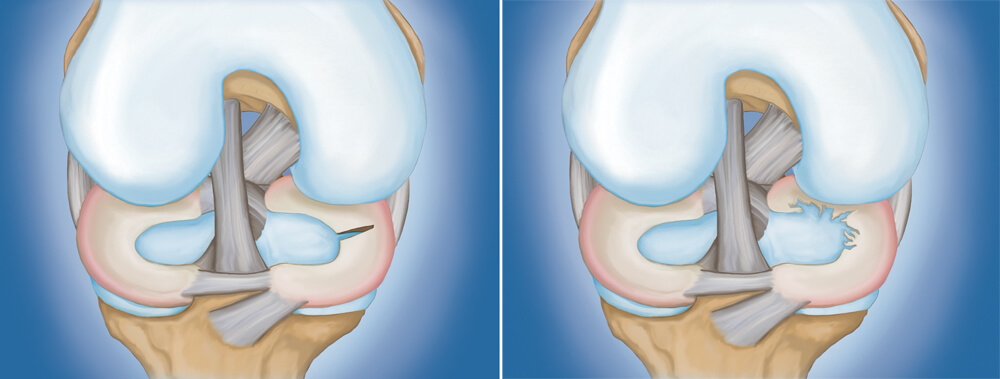

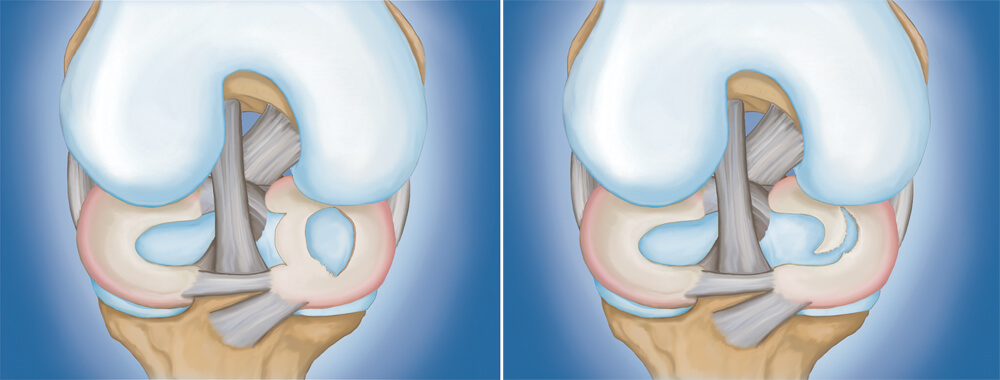

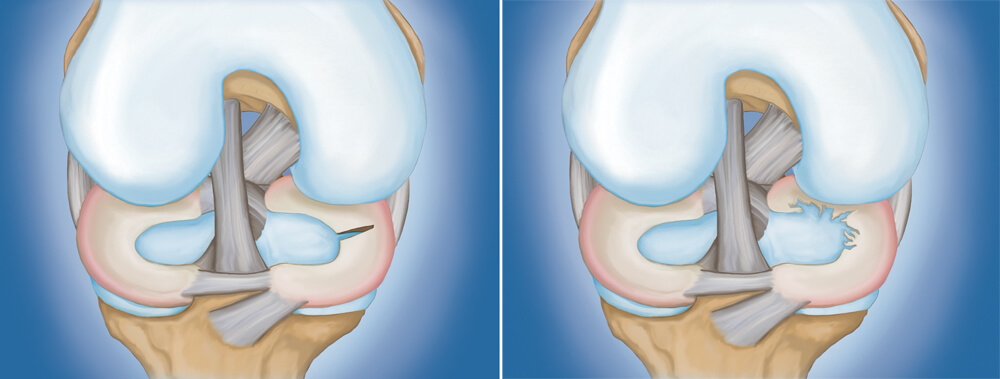

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

If your symptoms persist with nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may suggest arthroscopic surgery.

Procedure. Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a miniature camera through a small incision (portal) in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The surgeon then inserts surgical instruments through two or three other small portals to trim or repair the tear.

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

If your symptoms persist with nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may suggest arthroscopic surgery.

Procedure. Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a miniature camera through a small incision (portal) in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The surgeon then inserts surgical instruments through two or three other small portals to trim or repair the tear.

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen help reduce pain and swelling.

Steroid injection. Your doctor may inject a corticosteroid medication into your knee joint to help eliminate pain and swelling.

Other nonsurgical treatment. Biologics injections, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), are currently being studied and may show promise in the future for the treatment of meniscus tears.

If your symptoms persist with nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may suggest arthroscopic surgery.

Procedure. Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a miniature camera through a small incision (portal) in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The surgeon then inserts surgical instruments through two or three other small portals to trim or repair the tear.

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen help reduce pain and swelling.

Steroid injection. Your doctor may inject a corticosteroid medication into your knee joint to help eliminate pain and swelling.

Other nonsurgical treatment. Biologics injections, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), are currently being studied and may show promise in the future for the treatment of meniscus tears.

If your symptoms persist with nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may suggest arthroscopic surgery.

Procedure. Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a miniature camera through a small incision (portal) in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The surgeon then inserts surgical instruments through two or three other small portals to trim or repair the tear.

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

The treatment your doctor recommends will depend on a number of factors, including your age, symptoms, and activity level. They will also consider the type, size, and location of the injury.

The outer one-third of the meniscus has a rich blood supply. A tear in this “red” zone may heal on its own, or can often be repaired with surgery. A longitudinal tear is an example of this kind of tear.

In contrast, the inner two-thirds of the meniscus lacks a significant blood supply. Without nutrients from blood, tears in this “white” zone with limited blood flow cannot heal. Because the pieces cannot grow back together, symptomatic tears in this zone that do not respond to conservative treatment are usually trimmed surgically.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen help reduce pain and swelling.

Steroid injection. Your doctor may inject a corticosteroid medication into your knee joint to help eliminate pain and swelling.

Other nonsurgical treatment. Biologics injections, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), are currently being studied and may show promise in the future for the treatment of meniscus tears.

If your symptoms persist with nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may suggest arthroscopic surgery.

Procedure. Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a miniature camera through a small incision (portal) in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The surgeon then inserts surgical instruments through two or three other small portals to trim or repair the tear.

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

The treatment your doctor recommends will depend on a number of factors, including your age, symptoms, and activity level. They will also consider the type, size, and location of the injury.

The outer one-third of the meniscus has a rich blood supply. A tear in this “red” zone may heal on its own, or can often be repaired with surgery. A longitudinal tear is an example of this kind of tear.

In contrast, the inner two-thirds of the meniscus lacks a significant blood supply. Without nutrients from blood, tears in this “white” zone with limited blood flow cannot heal. Because the pieces cannot grow back together, symptomatic tears in this zone that do not respond to conservative treatment are usually trimmed surgically.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen help reduce pain and swelling.

Steroid injection. Your doctor may inject a corticosteroid medication into your knee joint to help eliminate pain and swelling.

Other nonsurgical treatment. Biologics injections, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), are currently being studied and may show promise in the future for the treatment of meniscus tears.

If your symptoms persist with nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may suggest arthroscopic surgery.

Procedure. Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a miniature camera through a small incision (portal) in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The surgeon then inserts surgical instruments through two or three other small portals to trim or repair the tear.

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

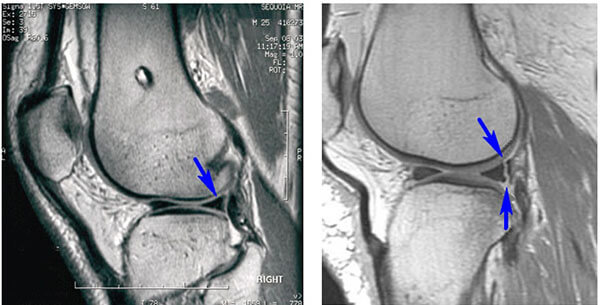

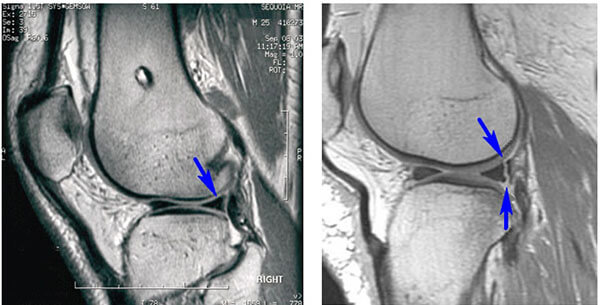

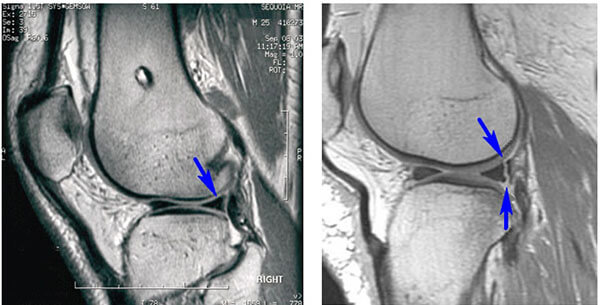

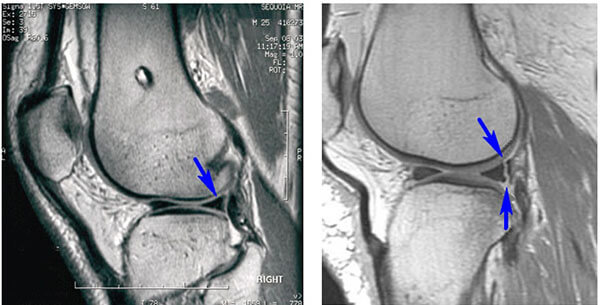

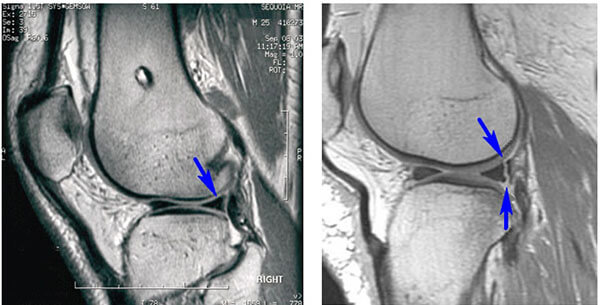

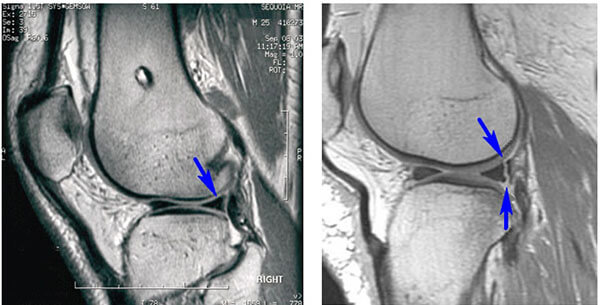

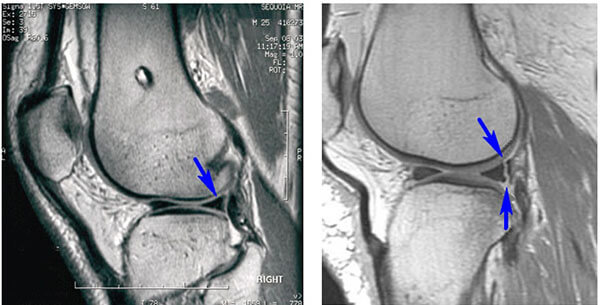

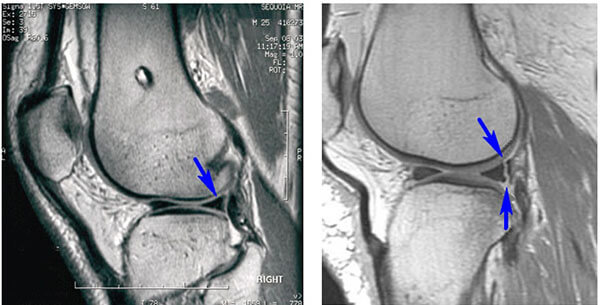

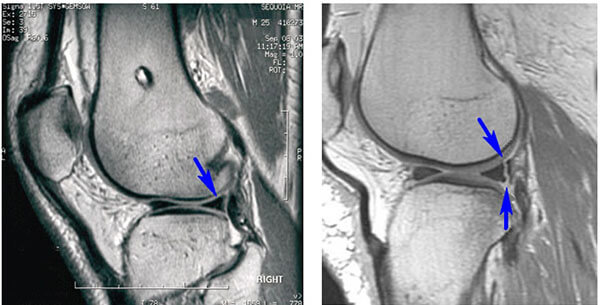

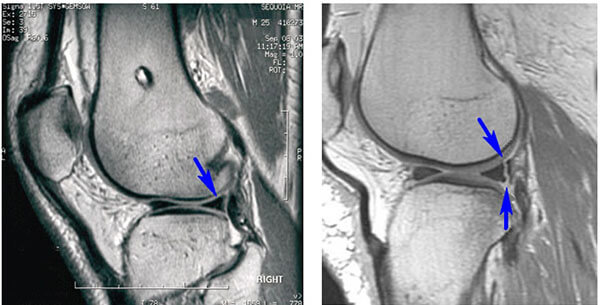

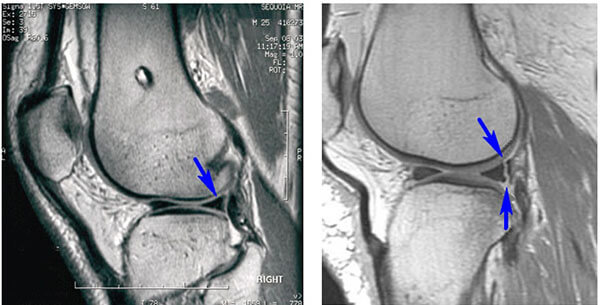

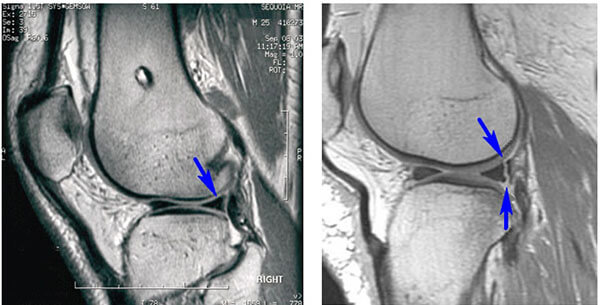

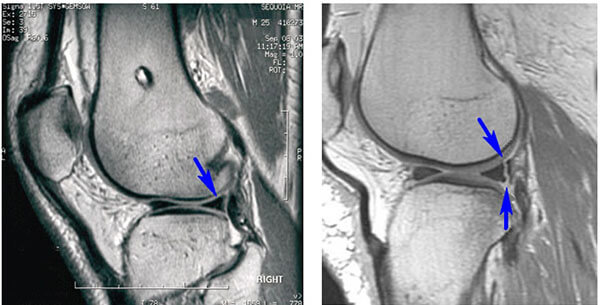

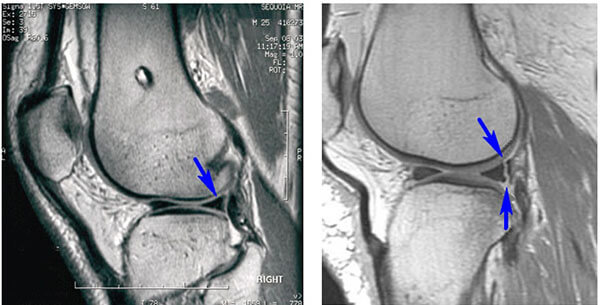

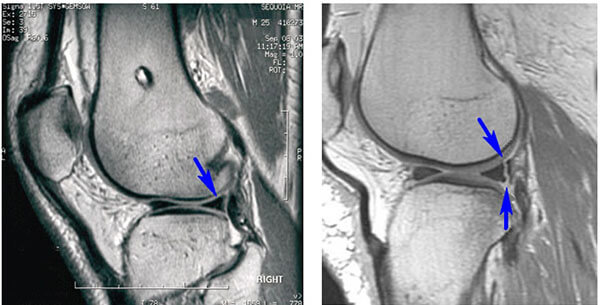

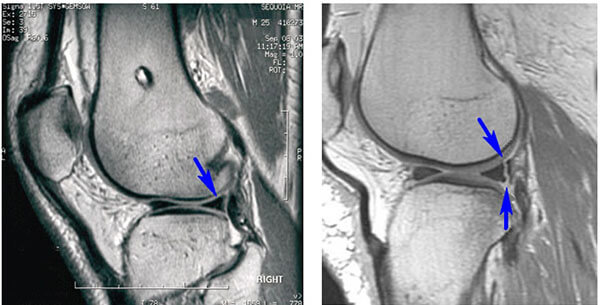

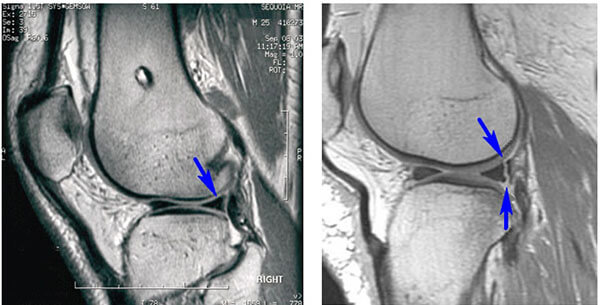

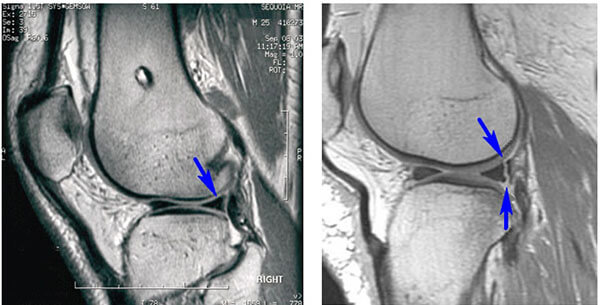

( MRI scans show (left) a normal meniscus and (right) a torn meniscus. The tear can be seen as a white line through the dark body of the meniscus )

The treatment your doctor recommends will depend on a number of factors, including your age, symptoms, and activity level. They will also consider the type, size, and location of the injury.

The outer one-third of the meniscus has a rich blood supply. A tear in this “red” zone may heal on its own, or can often be repaired with surgery. A longitudinal tear is an example of this kind of tear.

In contrast, the inner two-thirds of the meniscus lacks a significant blood supply. Without nutrients from blood, tears in this “white” zone with limited blood flow cannot heal. Because the pieces cannot grow back together, symptomatic tears in this zone that do not respond to conservative treatment are usually trimmed surgically.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen help reduce pain and swelling.

Steroid injection. Your doctor may inject a corticosteroid medication into your knee joint to help eliminate pain and swelling.

Other nonsurgical treatment. Biologics injections, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), are currently being studied and may show promise in the future for the treatment of meniscus tears.

If your symptoms persist with nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may suggest arthroscopic surgery.

Procedure. Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a miniature camera through a small incision (portal) in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The surgeon then inserts surgical instruments through two or three other small portals to trim or repair the tear.

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

( MRI scans show (left) a normal meniscus and (right) a torn meniscus. The tear can be seen as a white line through the dark body of the meniscus )

The treatment your doctor recommends will depend on a number of factors, including your age, symptoms, and activity level. They will also consider the type, size, and location of the injury.

The outer one-third of the meniscus has a rich blood supply. A tear in this “red” zone may heal on its own, or can often be repaired with surgery. A longitudinal tear is an example of this kind of tear.

In contrast, the inner two-thirds of the meniscus lacks a significant blood supply. Without nutrients from blood, tears in this “white” zone with limited blood flow cannot heal. Because the pieces cannot grow back together, symptomatic tears in this zone that do not respond to conservative treatment are usually trimmed surgically.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen help reduce pain and swelling.

Steroid injection. Your doctor may inject a corticosteroid medication into your knee joint to help eliminate pain and swelling.

Other nonsurgical treatment. Biologics injections, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), are currently being studied and may show promise in the future for the treatment of meniscus tears.

If your symptoms persist with nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may suggest arthroscopic surgery.

Procedure. Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a miniature camera through a small incision (portal) in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The surgeon then inserts surgical instruments through two or three other small portals to trim or repair the tear.

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

( MRI scans show (left) a normal meniscus and (right) a torn meniscus. The tear can be seen as a white line through the dark body of the meniscus )

The treatment your doctor recommends will depend on a number of factors, including your age, symptoms, and activity level. They will also consider the type, size, and location of the injury.

The outer one-third of the meniscus has a rich blood supply. A tear in this “red” zone may heal on its own, or can often be repaired with surgery. A longitudinal tear is an example of this kind of tear.

In contrast, the inner two-thirds of the meniscus lacks a significant blood supply. Without nutrients from blood, tears in this “white” zone with limited blood flow cannot heal. Because the pieces cannot grow back together, symptomatic tears in this zone that do not respond to conservative treatment are usually trimmed surgically.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen help reduce pain and swelling.

Steroid injection. Your doctor may inject a corticosteroid medication into your knee joint to help eliminate pain and swelling.

Other nonsurgical treatment. Biologics injections, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), are currently being studied and may show promise in the future for the treatment of meniscus tears.

If your symptoms persist with nonsurgical treatment, your doctor may suggest arthroscopic surgery.

Procedure. Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a miniature camera through a small incision (portal) in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The surgeon then inserts surgical instruments through two or three other small portals to trim or repair the tear.

( Illustration and photo show a camera and instruments inserted through portals in a knee )

( Close-up of partial meniscectomy )

( A torn meniscus repaired with sutures )

Once the initial healing is complete, your doctor will prescribe rehabilitation exercises. Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. You will start with exercises to improve your range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your rehabilitation plan.

In many cases, rehabilitation can be carried out at home, although your doctor may recommend working with a physical therapist. Rehabilitation time for a meniscus repair is about 3 to 6 months. A meniscectomy requires less time for healing — approximately 3 to 6 weeks.

Meniscus tears are extremely common knee injuries. With proper diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation, patients often return to their pre-injury abilities.

Activity modification: limit exposure to symptom provoking activity.

The primary goal of initial injury management is to manage symptoms. This may include avoidance of rapid movements, heavy lifting or dynamic/uncontrolled situations.

If you are an athlete, other options may include reducing overall workload or intensity of exercise, and limiting range of motion.

Oftentimes, athlete may become fear avoidant of performing a movement similar to the one that caused the injury. This, other goals may include improving confidence with movement. This can be achieved by the above mentioned recommendations.

Because other knee injuries can cause similar symptoms, your doctor may order imaging tests to help confirm the diagnosis.

X-rays. X-rays provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Although an X-ray will not show a meniscus tear, your doctor may order one to look for other causes of knee pain, such as osteoarthritis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. An MRI scan assesses the soft tissues in your knee joint, including the menisci, cartilage, tendons, and ligaments.

( MRI scans show (left) a normal meniscus and (right) a torn meniscus. The tear can be seen as a white line through the dark body of the meniscus )

The treatment your doctor recommends will depend on a number of factors, including your age, symptoms, and activity level. They will also consider the type, size, and location of the injury.

The outer one-third of the meniscus has a rich blood supply. A tear in this “red” zone may heal on its own, or can often be repaired with surgery. A longitudinal tear is an example of this kind of tear.

In contrast, the inner two-thirds of the meniscus lacks a significant blood supply. Without nutrients from blood, tears in this “white” zone with limited blood flow cannot heal. Because the pieces cannot grow back together, symptomatic tears in this zone that do not respond to conservative treatment are usually trimmed surgically.