Types of grappling grips

This video describes the various grips used in grappling (wrestling, jiu jitsu, mma, judo).

This video describes the various grips used in grappling (wrestling, jiu jitsu, mma, judo).

This video describes different types of strength training workouts with a gi for Brazilian jiu jitsu and judo athletes. It builds upon the previous work of the hand and wrist anatomy and grips used in grappling sports.

Bone related injuries occur in different rates in different sports. These include fractures or bone stress-related incidents. Injuries can be acute, like falling on an outstretched arm and fracturing the wrist; or they can be chronic, like stress fractures that accumulate over time due to inadequate rest or nutrition deficiencies.

Athletes are exposed to more frequent injuries of the legs in certain sports like soccer, football or rugby. Upper body injuries are more frequent in sports like baseball, volleyball or gymnastics.

Many athletes and coaches are often unsure of when to refer out for diagnostic imaging (MRI, x-ray) to rule out a serious injury like a fracture. Sometimes, an obvious injury like falling from a box onto the head, would warrant immediate referral to the ER. Other times, a deep, dull, aching discomfort that has been present for weeks may not be overly suspicious, but can still be a sign of a more serious injury to an observant individual.

Athletes may be encouraged to use ice, rest and different braces to manage pain while continuing to participate in sport. This may be a modestly effective treatment for some injuries, but it can be disastrous for others.

Sports related injuries of the neck, knee and ankle can cause a range of symptoms from mild discomfort to severe and debilitating pain. Having a health care provider onsite at the time of injury is always the best. However, in the event that one is not available, coaches, parents or athletes may need to determine how to best address the injured athlete in front of them.

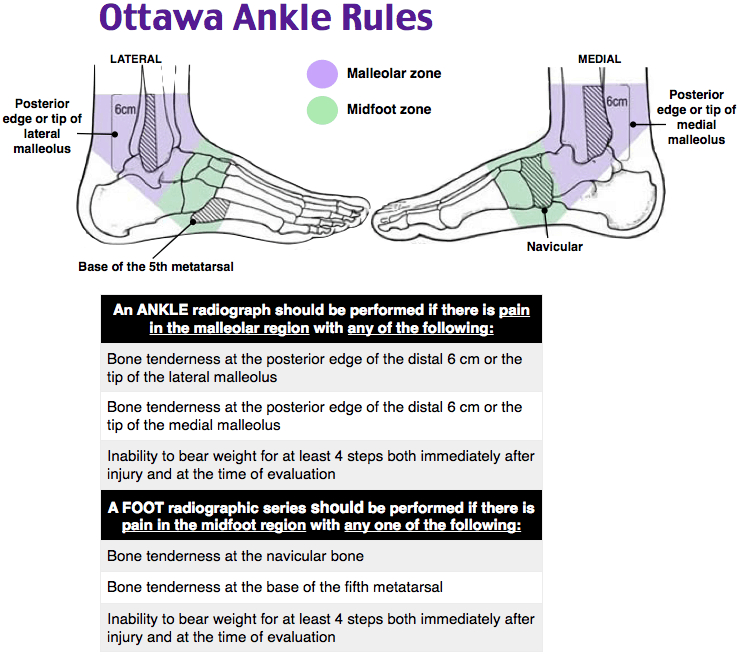

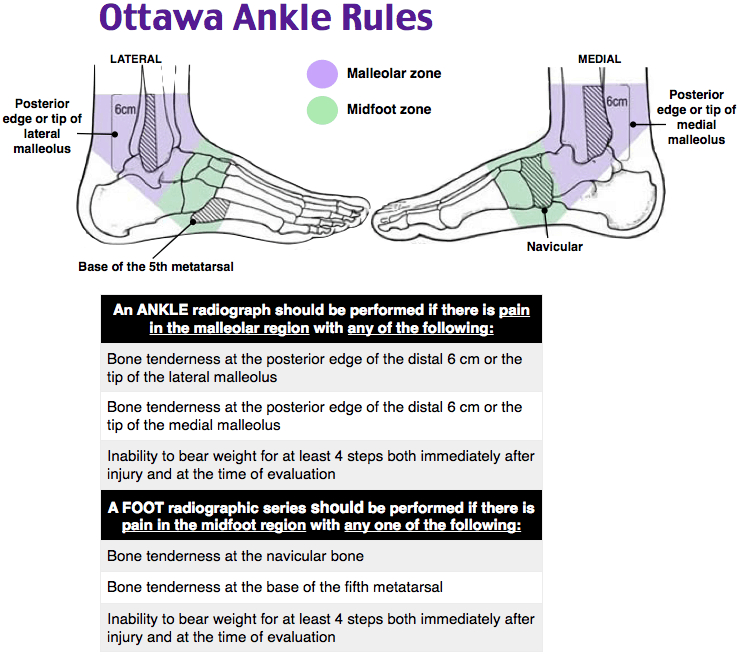

Using algorithms to determine the best imaging can help reduce health care costs, time and unnecessary exposure to radiation. The Ottawa Rules were designed to assist clinicians with determining when to refer an individual for radiographs (x-rays) when admitted to the emergency room.

The creator, Dr. Ian Stiell states “We found that emergency doctors were ordering many imaging studies for ankle injuries that were then found to be normal. I thought if there were a set a rules with criteria developed by emergency physicians, for emergency physicians, they would help this problem and shorten emergency department wait times and costs.”

Below are the algorithms used to determine proper referral for imaging for the ankle, knee, neck and head.

Each algorithm is designed to be as sensitive as possible. That means that the researchers wanted to minimize the number of people that should have been referred for radiographs, but weren’t.

These tests should be administered by a qualified health care provider.

The Ottawa ankle rule states that if the person has tenderness on at least one of the points indicated on the picture and cannot bear weight on the injured foot for at least 5 steps, they should be referred for x-ray.

The Ottawa knee rule states that if the person is older than 55, has tenderness to the patella (knee cap) or fibular head, cannot bend the knee more than 90 degrees, and cannot walk 4 weight bearing steps, they should be referred for radiographs.

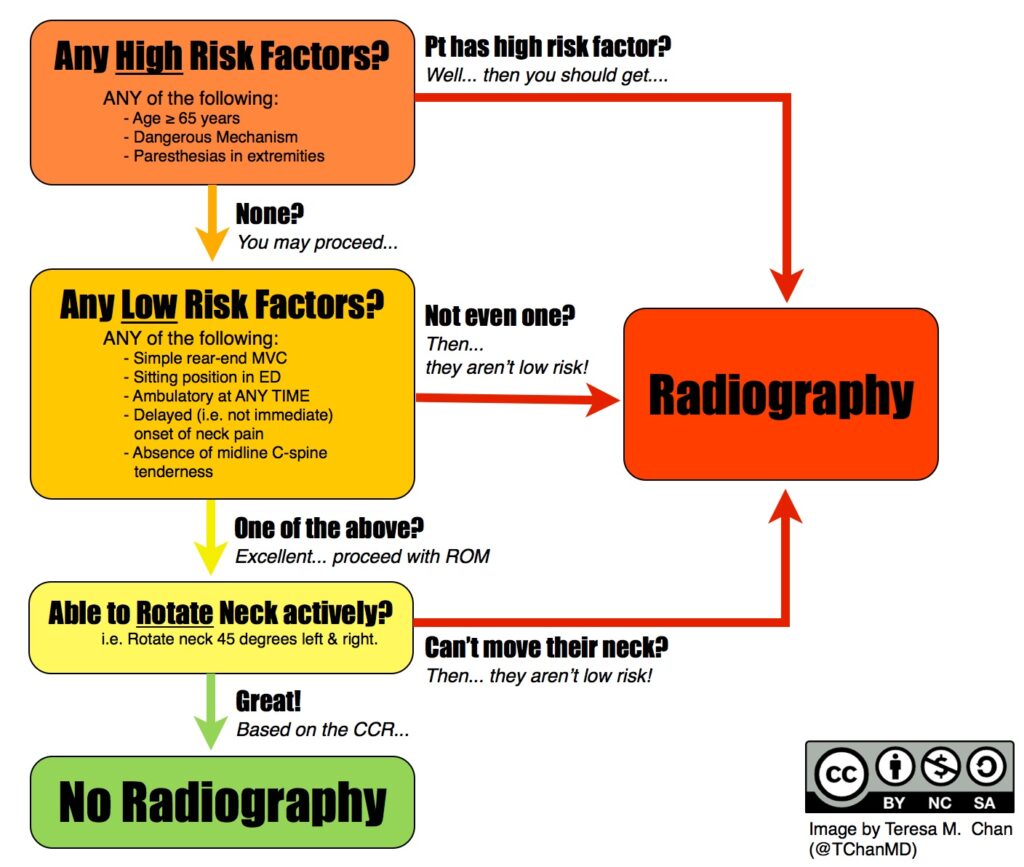

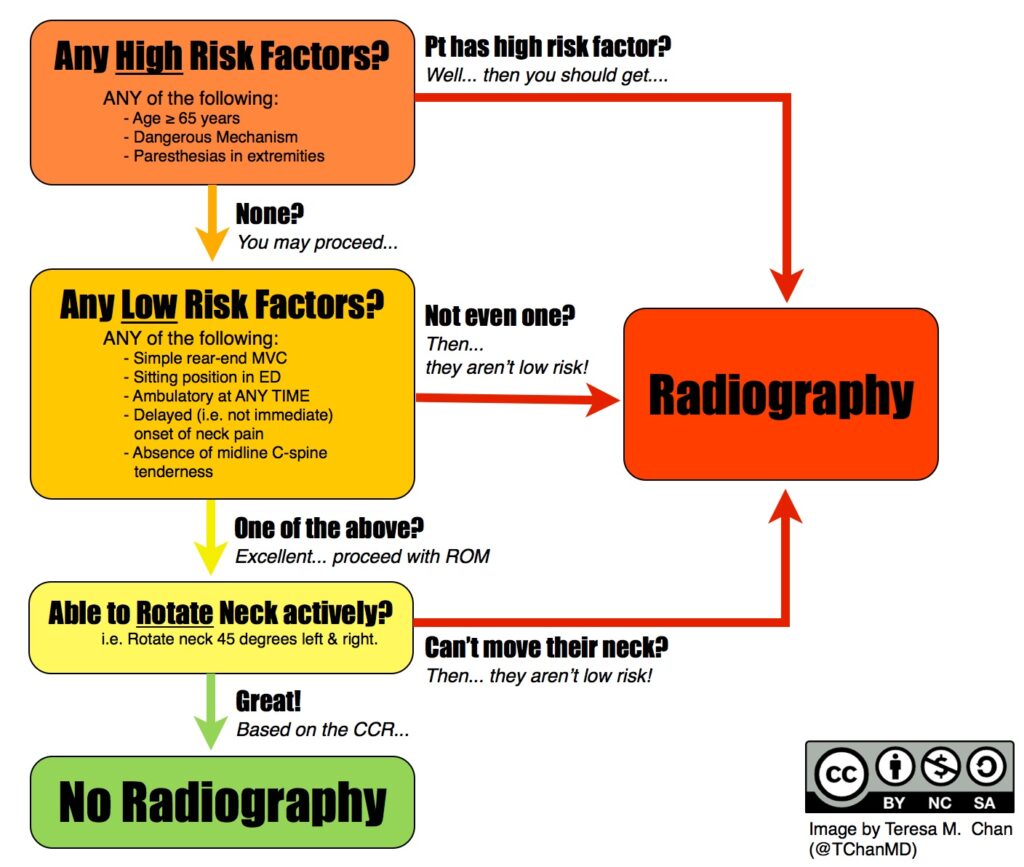

The Canadia C-Spine rules follow a flow chart, ruling out specific risk factors, directing to radiographs or additional questions, until all questions are satisfied.

The Canadian CT Head Injury requires quite a bit more medical knowledge. The assessment begins with a measurement of consciousness, then proceeds to a risk factor flow chart. The clinician then determines the utility in ordering a CT scan of the head.

The information present in this post should not substitute medical advice. Direct communication with a health care professional should always be the first option.

The information present in this post should not substitute medical advice. Direct communication with a health care professional should always be the first option.

Bone related injuries occur in different rates in different sports. These include fractures or bone stress-related incidents. Injuries can be acute, like falling on an outstretched arm and fracturing the wrist; or they can be chronic, like stress fractures that accumulate over time due to inadequate rest or nutrition deficiencies.

Athletes are exposed to more frequent injuries of the legs in certain sports like soccer, football or rugby. Upper body injuries are more frequent in sports like baseball, volleyball or gymnastics.

Many athletes and coaches are often unsure of when to refer out for diagnostic imaging (MRI, x-ray) to rule out a serious injury like a fracture. Sometimes, an obvious injury like falling from a box onto the head, would warrant immediate referral to the ER. Other times, a deep, dull, aching discomfort that has been present for weeks may not be overly suspicious, but can still be a sign of a more serious injury to an observant individual.

Athletes may be encouraged to use ice, rest and different braces to manage pain while continuing to participate in sport. This may be a modestly effective treatment for some injuries, but it can be disastrous for others.

Sports related injuries of the neck, knee and ankle can cause a range of symptoms from mild discomfort to severe and debilitating pain. Having a health care provider onsite at the time of injury is always the best. However, in the event that one is not available, coaches, parents or athletes may need to determine how to best address the injured athlete in front of them.

Using algorithms to determine the best imaging can help reduce health care costs, time and unnecessary exposure to radiation. The Ottawa Rules were designed to assist clinicians with determining when to refer an individual for radiographs (x-rays) when admitted to the emergency room.

The creator, Dr. Ian Stiell states “We found that emergency doctors were ordering many imaging studies for ankle injuries that were then found to be normal. I thought if there were a set a rules with criteria developed by emergency physicians, for emergency physicians, they would help this problem and shorten emergency department wait times and costs.”

Below are the algorithms used to determine proper referral for imaging for the ankle, knee, neck and head.

Each algorithm is designed to be as sensitive as possible. That means that the researchers wanted to minimize the number of people that should have been referred for radiographs, but weren’t.

These tests should be administered by a qualified health care provider.

The Ottawa ankle rule states that if the person has tenderness on at least one of the points indicated on the picture and cannot bear weight on the injured foot for at least 5 steps, they should be referred for x-ray.

The Ottawa knee rule states that if the person is older than 55, has tenderness to the patella (knee cap) or fibular head, cannot bend the knee more than 90 degrees, and cannot walk 4 weight bearing steps, they should be referred for radiographs.

The Canadia C-Spine rules follow a flow chart, ruling out specific risk factors, directing to radiographs or additional questions, until all questions are satisfied.

The Canadian CT Head Injury requires quite a bit more medical knowledge. The assessment begins with a measurement of consciousness, then proceeds to a risk factor flow chart. The clinician then determines the utility in ordering a CT scan of the head.

The information present in this post should not substitute medical advice. Direct communication with a health care professional should always be the first option.

There is limited evidence that quadriceps flexibility is a risk factor for hamstring injury.

There is limited evidence that hip extension asymmetry >15% is associated with musculoskeletal injury.

There is moderate evidence of an association between hamstring flexibility and muscluloskeletal injury. Individuals with too short, or too long hamstrings are at a 3x risk of experiencing a hamstring injury.

There is moderate evidence that asymmetry in ankle flexion >6.4 degrees is associated with ~5x risk of experiencing a musculoskeletal injury.

There is moderate evidence that supports associated between lower body musculoskeletal risk and lower body power. However, some studies demonstrate an increased risk for both high and low power athletes. One study demonstrates that for army conscripts in Finland that had poor broad jump distances, were ~2x more likely to experience an injury. Another study demonstrated in professional male soccer players that had a higher vertical jump were 1.5x more likely to suffer a hamstring injury.

There is moderate evidence that slower sprint speed is associated with ~10x more likely to be injured than those with faster speeds at 10, 40 and 300 meters distances.

There is moderate evidence that demonstrates a 2.5x increased injury risk in ankle sprain injuries in athletes that have poor single leg balance.

Despite the growing field of research in injury assessment and risk management, there are quite a few unanswered questions. Standardization of measurements, sport-specific assessments, and more robust association in findings would help clear up many of these questions.

Practical application and programming for athletes and careers that require high fitness levels should also be discussed within the research community. Perhaps guidelines may help coaches develop pre-season injury assessments and provide strength and conditioning programs that are athlete-specific, essentially reducing the number of athletes sitting on the sidelines due to injury.

If you are an athlete or coach in Miami, FL and find this topic interesting, or want more information, reach out to our office for assistance.

Determining injury risk for athletes is a challenging task. While much research has been done in this field for decades, the mechanisms for assessing risk of injury have not been fully elucidated. General principles and guidelines have been adopted by clinicians, but these can vary widely by sport, gender, exercise history, injury history and a host of other intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

In this article we will discuss what the literature suggests in regards to how flexibility, speed, power, balance and agility may play a role in injury prevention. These findings are important to a large and heterogenous population. Individuals engaged in careers that require a high level of fitness (SWAT officers, FBI agents) and athletes can benefit from this research.

Organizations that manage tactical athletes (SWAT, FBI field agents) can better assess and develop physical fitness protocols using these markers as general guidelines for health and fitness. A large economic burden placed on the health system when officers are injured. Time off, changes in work duties, surgery and rehabilitation can drastically change the career trajectory of an injured agent.

Coaches can better program exercises for athletes and athletes can use these guidelines to help identify areas that need work.

Of important note, is that these values are not definitive. Being outside of a hypothetical “high risk” category, does not mean you will never be injured. Similarly, just because you are in a “high risk” category, does not mean you shouldn’t participate in sports or join a career that requires a high level of fitness.

Lets take a look at each category. For the sake of keeping things simple to digest, I will keep the description brief and delve into the geeky science stuff. If you wish to read the original article, you can find it here.

There is limited evidence that quadriceps flexibility is a risk factor for hamstring injury.

There is limited evidence that hip extension asymmetry >15% is associated with musculoskeletal injury.

There is moderate evidence of an association between hamstring flexibility and muscluloskeletal injury. Individuals with too short, or too long hamstrings are at a 3x risk of experiencing a hamstring injury.

There is moderate evidence that asymmetry in ankle flexion >6.4 degrees is associated with ~5x risk of experiencing a musculoskeletal injury.

There is moderate evidence that supports associated between lower body musculoskeletal risk and lower body power. However, some studies demonstrate an increased risk for both high and low power athletes. One study demonstrates that for army conscripts in Finland that had poor broad jump distances, were ~2x more likely to experience an injury. Another study demonstrated in professional male soccer players that had a higher vertical jump were 1.5x more likely to suffer a hamstring injury.

There is moderate evidence that slower sprint speed is associated with ~10x more likely to be injured than those with faster speeds at 10, 40 and 300 meters distances.

There is moderate evidence that demonstrates a 2.5x increased injury risk in ankle sprain injuries in athletes that have poor single leg balance.

Despite the growing field of research in injury assessment and risk management, there are quite a few unanswered questions. Standardization of measurements, sport-specific assessments, and more robust association in findings would help clear up many of these questions.

Practical application and programming for athletes and careers that require high fitness levels should also be discussed within the research community. Perhaps guidelines may help coaches develop pre-season injury assessments and provide strength and conditioning programs that are athlete-specific, essentially reducing the number of athletes sitting on the sidelines due to injury.

If you are an athlete or coach in Miami, FL and find this topic interesting, or want more information, reach out to our office for assistance.

There is strong evidence of an association between slow running time on a set distance. These studies were conducted largely in military basic training or equivalent.

There is strong evidence of an association between poor intermittent run tests and increased risk of injury. Poor performers were 6x more likely to suffer an injury.

There is insufficient evidence of an association between MAGT and injury risk. Two good studies failed to find any significant association in professional soccer players and US Army trainees.

There is limited evidence for distance covered and overuse injury. Finnish military conscripts that ran the least distance were 1.4x more likely to experience an overuse injury.

It seems that there is enough evidence to use aerobic fitness as an indicator of injury risk. Several methods may be used, and they appear to be valid in several types of populations.

Coaches, athletes and health care professionals should be cautious with how they use this data. While the data may indicate a hypothetical risk, risk should be assessed on an individual level.

Can your ability to run a mile predict your risk for developing an injury?

Injuries to the musculoskeletal system are the leading cause of lost duty days in military service members, and are the most common cause for ER visits in athletes and first responders. There is a large economic burden and potential for long term health complications associated with these types of injuries.

While some risk factors including age and gender cannot be modified and are associated with increased risk, other risk factors are. Training load, footwear and physical fitness are three areas that can be modified with intervention. Physical fitness is defined as a combination of cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular endurance, power, strength & flexibility.

Of important note, is that these values are not definitive. Being outside of a hypothetical “high risk” category, does not mean you will never be injured. Similarly, just because you are in a “high risk” category, does not mean you shouldn’t participate in sports or join a career that requires a high level of fitness.

The categories are divided into what type of aerobic test was considered, the level of evidence for determining risk assessment, and other pertinent information. For the sake of keeping things simple to digest, I will keep the description brief and delve into the geeky science stuff. If you wish to read the original article, you can find it here.

There is strong evidence of an association between slow running time on a set distance. These studies were conducted largely in military basic training or equivalent.

There is strong evidence of an association between poor intermittent run tests and increased risk of injury. Poor performers were 6x more likely to suffer an injury.

There is insufficient evidence of an association between MAGT and injury risk. Two good studies failed to find any significant association in professional soccer players and US Army trainees.

There is limited evidence for distance covered and overuse injury. Finnish military conscripts that ran the least distance were 1.4x more likely to experience an overuse injury.

It seems that there is enough evidence to use aerobic fitness as an indicator of injury risk. Several methods may be used, and they appear to be valid in several types of populations.

Coaches, athletes and health care professionals should be cautious with how they use this data. While the data may indicate a hypothetical risk, risk should be assessed on an individual level.

There is limited evidence for women and moderate evidence in men that poor sit-up scores increase injury risk.

There is insufficient evidence to support score on pull-up tasks as a risk factor for injury.

Isokinetic testing: moderate evidence on association of isokinetic muscle strength of the ankle, although direction cannot be definitively determined. Moderate evidence that knee flexion strength is associated with injury.

Isotonic testing: there is limited association that upper, lower or full body isotonic testing can predict injury risk.

Isometric testing: isometric strength testing is moderately associated with injury risk, and the direction of association cannot be stated.

Test to failure: Researchers also looked at “tests to failure” like holding a weight, bench pressing, planks, crunch hold and wall-sits. There was a moderate amount of evidence that these tests can predict injury risk.

Composite Fitness scores: there is moderate evidence that fitness scores (a battery of tests including sit-ups, pushups, pull-ups and back extensions) are associated with injury risk, direction cannot be stated.

It is interesting to note that there were differences in injury risk based on gender and athletic capability. Studies demonstrate differences in risk between genders (pushups and sit ups). Weak upper body and abdominal strength/endurance was predictive of injury in men, but limited in females. Individuals with weaker or very strong lower body strength were at higher risk of injury. It is hypothesized that people with very strong lower bodies may apply themselves more or perhaps engage in more risky behavior when training, thus increasing injury risk. A study of Finnish soldiers that scored in the upper quartiles were 3.5x more likely to experience meniscus injury and 2.6x more likely to sustain an ACL or PCL injury.

Who can benefit from this information? Tactical athletes (SWAT, FBI field agents, police officers), non-combatants such as fire fighters and paramedics, and athletes.

There is strong evidence that pushups are associated with increased injury risk in males.

There is limited evidence that pushups are associated with increased injury risk in females.

There is limited evidence for women and moderate evidence in men that poor sit-up scores increase injury risk.

There is insufficient evidence to support score on pull-up tasks as a risk factor for injury.

Isokinetic testing: moderate evidence on association of isokinetic muscle strength of the ankle, although direction cannot be definitively determined. Moderate evidence that knee flexion strength is associated with injury.

Isotonic testing: there is limited association that upper, lower or full body isotonic testing can predict injury risk.

Isometric testing: isometric strength testing is moderately associated with injury risk, and the direction of association cannot be stated.

Test to failure: Researchers also looked at “tests to failure” like holding a weight, bench pressing, planks, crunch hold and wall-sits. There was a moderate amount of evidence that these tests can predict injury risk.

Composite Fitness scores: there is moderate evidence that fitness scores (a battery of tests including sit-ups, pushups, pull-ups and back extensions) are associated with injury risk, direction cannot be stated.

It is interesting to note that there were differences in injury risk based on gender and athletic capability. Studies demonstrate differences in risk between genders (pushups and sit ups). Weak upper body and abdominal strength/endurance was predictive of injury in men, but limited in females. Individuals with weaker or very strong lower body strength were at higher risk of injury. It is hypothesized that people with very strong lower bodies may apply themselves more or perhaps engage in more risky behavior when training, thus increasing injury risk. A study of Finnish soldiers that scored in the upper quartiles were 3.5x more likely to experience meniscus injury and 2.6x more likely to sustain an ACL or PCL injury.

Who can benefit from this information? Tactical athletes (SWAT, FBI field agents, police officers), non-combatants such as fire fighters and paramedics, and athletes.

Given the active nature of military and law enforcement, musculoskeletal injury is a leading cause of disability and time off. Exposure to new physical training programs, coupled with high stress environments, can increase injury risk and may result in a large financial and logistic complications.

During the initial training camp for the military, about 25% of male and 55% of female recruits will experience at least one musculoskeletal injury. Injuries are divided into modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. Modifiable risk factors include training program, footwear & equipment. Non-modifiable risk factors include gender, age and previous injury history.

In this article we will discuss the research findings that attempted to identify specific tests of muscular strength and endurance that could predict the risk of injury. The majority of studies were in military and law enforcement (male and female) and professional athletes.

The research is based on a total of 45 articles written between 1970 and 2015 that included male and females, between18-65 years old, with reports on physical fitness measures (pushups, setups etc…) and injury exposure (acute, overuse). Injury was defined as the individual being treated by a health care provider.

The majority (69%) of studies were conducted in the military environment, mostly in basic training (61%). The remaining studies were done in professional athletes (13%), collegiate athletes (11%), physical education majors (4%) and FBI trainees (3%).

There is strong evidence that pushups are associated with increased injury risk in males.

There is limited evidence that pushups are associated with increased injury risk in females.

There is limited evidence for women and moderate evidence in men that poor sit-up scores increase injury risk.

There is insufficient evidence to support score on pull-up tasks as a risk factor for injury.

Isokinetic testing: moderate evidence on association of isokinetic muscle strength of the ankle, although direction cannot be definitively determined. Moderate evidence that knee flexion strength is associated with injury.

Isotonic testing: there is limited association that upper, lower or full body isotonic testing can predict injury risk.

Isometric testing: isometric strength testing is moderately associated with injury risk, and the direction of association cannot be stated.

Test to failure: Researchers also looked at “tests to failure” like holding a weight, bench pressing, planks, crunch hold and wall-sits. There was a moderate amount of evidence that these tests can predict injury risk.

Composite Fitness scores: there is moderate evidence that fitness scores (a battery of tests including sit-ups, pushups, pull-ups and back extensions) are associated with injury risk, direction cannot be stated.

It is interesting to note that there were differences in injury risk based on gender and athletic capability. Studies demonstrate differences in risk between genders (pushups and sit ups). Weak upper body and abdominal strength/endurance was predictive of injury in men, but limited in females. Individuals with weaker or very strong lower body strength were at higher risk of injury. It is hypothesized that people with very strong lower bodies may apply themselves more or perhaps engage in more risky behavior when training, thus increasing injury risk. A study of Finnish soldiers that scored in the upper quartiles were 3.5x more likely to experience meniscus injury and 2.6x more likely to sustain an ACL or PCL injury.

Who can benefit from this information? Tactical athletes (SWAT, FBI field agents, police officers), non-combatants such as fire fighters and paramedics, and athletes.

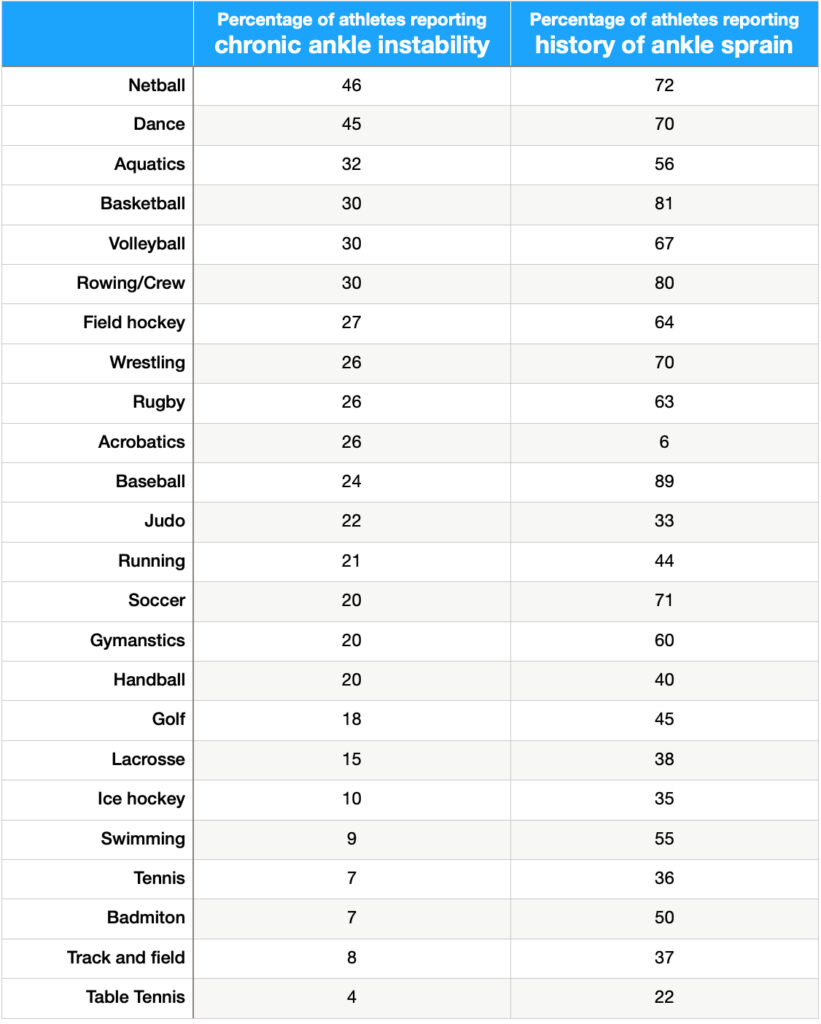

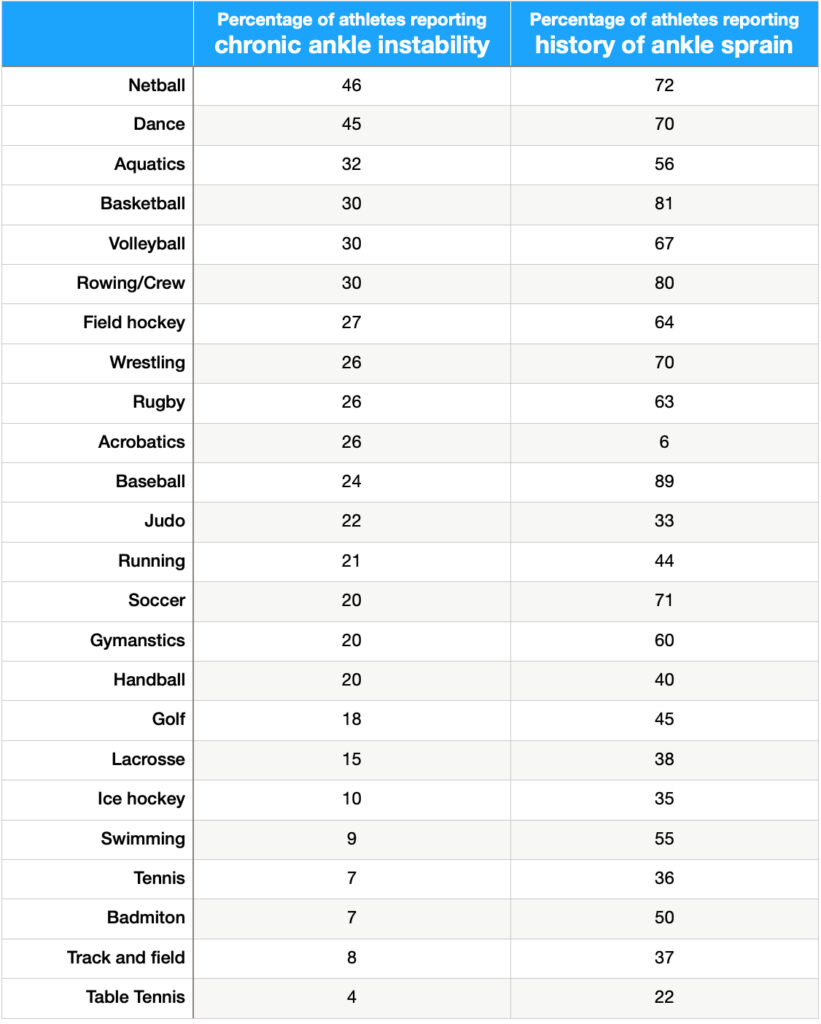

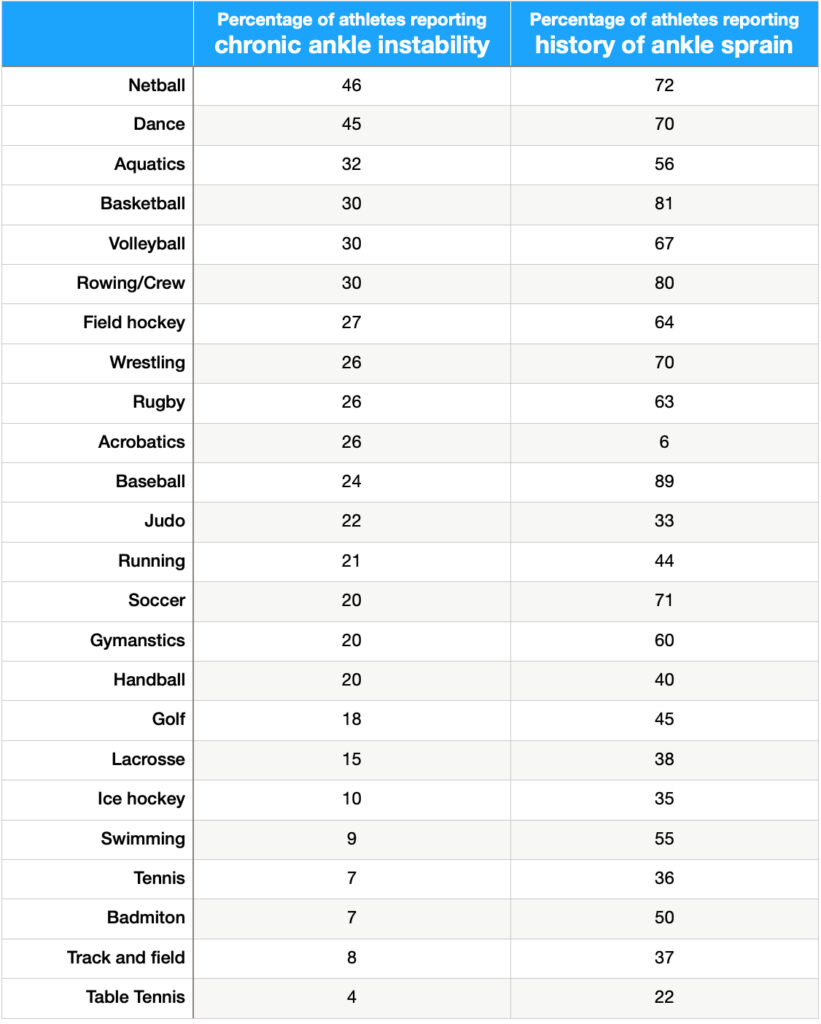

While data points towards “field sports” such as football, soccer and volleyball as high risk sports, ankle sprains can occur with participation in other athletic events including dance, judo, jiu jitsu and gymnastics.

The table below shows percentages of athletes within a specific sport that have chronic ankle instability and the percentage of athletes reporting a history of ankle pain.

Gender differences exist: females, are twice as likely to experience an ankle sprain. While the literature is unclear as to specific causes, several biomechanical, hormonal and musculoskeletal theories have been proposed, but are generally inconclusive.

It is interesting to note that very few people seek care from emergency care. This has been postulated to be due to most individuals being able to “get by” once the swelling and acute pain have subsided. Swelling often takes a week or 2 to resolve. A typical treatment approach for early intervention is the RICE method. Rest, Ice, compression & elevation. While this may help considerably in the short term, with most people can go about their daily routine, a large percentage (between 20-46%) will experience a subsequent injury within a year. Surveys demonstrate that 73% of athletes have sustained two sprains of the same ankle.

There have been algorithms that help medical professionals determine whether or not an athlete should have diagnostic imaging (x-rays) in an emergency situation. You can find that article HERE.

Reinjury rates vary between 20% (low) and 46% (high), depending on the level of activity, sport participation and other factors. Indeed, a previous ankle sprain is the biggest predictor for experiencing a subsequent sprain. Once injured, there is a 3.5x greater risk of experiencing a second ankle sprain.

Chronic ankle instability develops in about 70% of athletes after the first ankle sprain. This condition is described as a significant ankle sprain, feelings of instability or more than 2 episodes of giving way in the past 6 months.

Post-traumatic osteoarthritis may develop in the affected ankle as well. This is characterized by early degeneration of joint cartilage due to the high velocity trauma (acute), in addition to altered joint movement after the injury (chronic, repetitive). Because ankle sprains occur most often in youth and adolescent athletes, this may cause painful walking and participation in sports later on in life. Of all post-traumatic osteoarthritis cases of the ankle, 80% could be attributed to an ankle sprain earlier in life.

The good news is that there is plenty of research demonstrating that specific interventions can significantly reduce the risk of subsequent injury by 81%! Professional soccer teams that adopted the FIFA 11+ protocol were able to reduce lower extremity injury by 30%. With a 46% reinjury rate, athletes should be JUMPING at that opportunity. Given the post-injury complications, engaging in a quality program is well worth the investment if it means pursuing your passion.

Absolutely! I have helped hundreds of performing artists at Royal Caribbean and Celebrity cruises with many types of injuries. And performing artists are known for ankle injuries! Early intervention, coupled with confidence building and strength training exercises have helped high level athletes continue on with their career.

The most important thing is that a proper history, evaluation and program tailored to your specific goals are completed. Few physical therapists understand the commitment athletes make- sacrificing hanging out with friends to make practice. Sacrificing vacations to compete. I’ve been there and I’ve done that, now I want to help the next generation of athletes stay active and healthy.

A quick phone call will help determine what the best course of action for you is. We can set that up by having you call the number below.

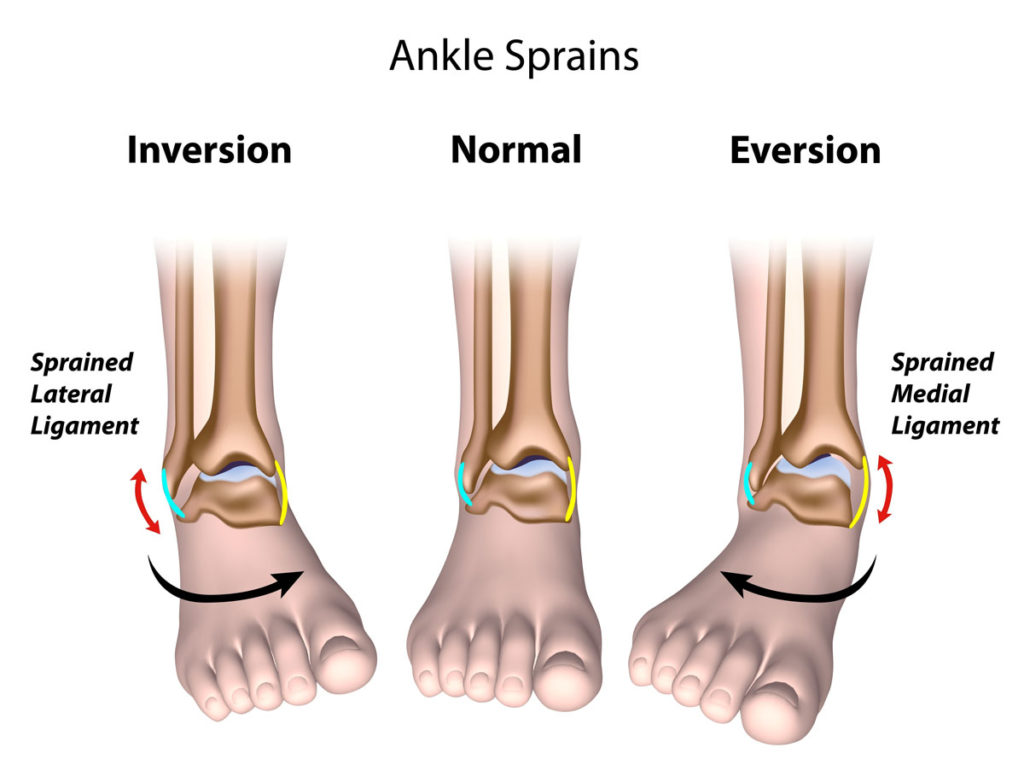

In the athletic population, for every 1000 athlete exposures (training session, game, performance), there is 1 athlete that will experience a lateral ankle injury. Medial and high ankle sprains are much less common. Of all ankle sprains, 3/4 are of the lateral ankle and 1/4 are of the medial or high ankle.

While data points towards “field sports” such as football, soccer and volleyball as high risk sports, ankle sprains can occur with participation in other athletic events including dance, judo, jiu jitsu and gymnastics.

The table below shows percentages of athletes within a specific sport that have chronic ankle instability and the percentage of athletes reporting a history of ankle pain.

Gender differences exist: females, are twice as likely to experience an ankle sprain. While the literature is unclear as to specific causes, several biomechanical, hormonal and musculoskeletal theories have been proposed, but are generally inconclusive.

It is interesting to note that very few people seek care from emergency care. This has been postulated to be due to most individuals being able to “get by” once the swelling and acute pain have subsided. Swelling often takes a week or 2 to resolve. A typical treatment approach for early intervention is the RICE method. Rest, Ice, compression & elevation. While this may help considerably in the short term, with most people can go about their daily routine, a large percentage (between 20-46%) will experience a subsequent injury within a year. Surveys demonstrate that 73% of athletes have sustained two sprains of the same ankle.

There have been algorithms that help medical professionals determine whether or not an athlete should have diagnostic imaging (x-rays) in an emergency situation. You can find that article HERE.

Reinjury rates vary between 20% (low) and 46% (high), depending on the level of activity, sport participation and other factors. Indeed, a previous ankle sprain is the biggest predictor for experiencing a subsequent sprain. Once injured, there is a 3.5x greater risk of experiencing a second ankle sprain.

Chronic ankle instability develops in about 70% of athletes after the first ankle sprain. This condition is described as a significant ankle sprain, feelings of instability or more than 2 episodes of giving way in the past 6 months.

Post-traumatic osteoarthritis may develop in the affected ankle as well. This is characterized by early degeneration of joint cartilage due to the high velocity trauma (acute), in addition to altered joint movement after the injury (chronic, repetitive). Because ankle sprains occur most often in youth and adolescent athletes, this may cause painful walking and participation in sports later on in life. Of all post-traumatic osteoarthritis cases of the ankle, 80% could be attributed to an ankle sprain earlier in life.

The good news is that there is plenty of research demonstrating that specific interventions can significantly reduce the risk of subsequent injury by 81%! Professional soccer teams that adopted the FIFA 11+ protocol were able to reduce lower extremity injury by 30%. With a 46% reinjury rate, athletes should be JUMPING at that opportunity. Given the post-injury complications, engaging in a quality program is well worth the investment if it means pursuing your passion.

Absolutely! I have helped hundreds of performing artists at Royal Caribbean and Celebrity cruises with many types of injuries. And performing artists are known for ankle injuries! Early intervention, coupled with confidence building and strength training exercises have helped high level athletes continue on with their career.

The most important thing is that a proper history, evaluation and program tailored to your specific goals are completed. Few physical therapists understand the commitment athletes make- sacrificing hanging out with friends to make practice. Sacrificing vacations to compete. I’ve been there and I’ve done that, now I want to help the next generation of athletes stay active and healthy.

A quick phone call will help determine what the best course of action for you is. We can set that up by having you call the number below.

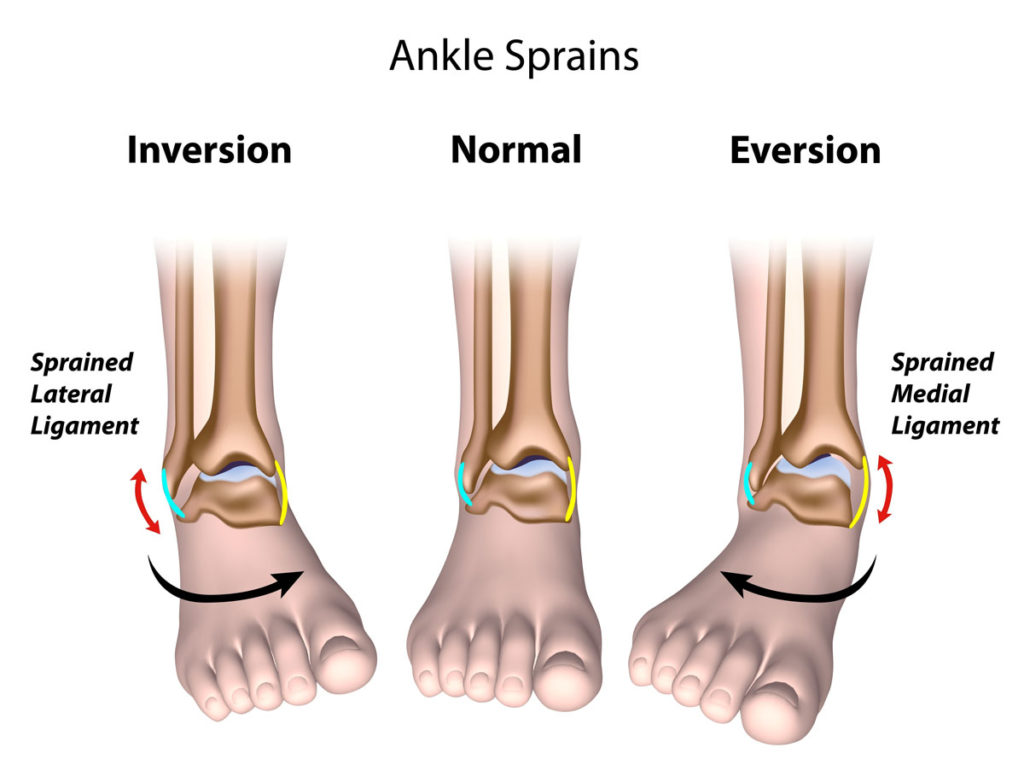

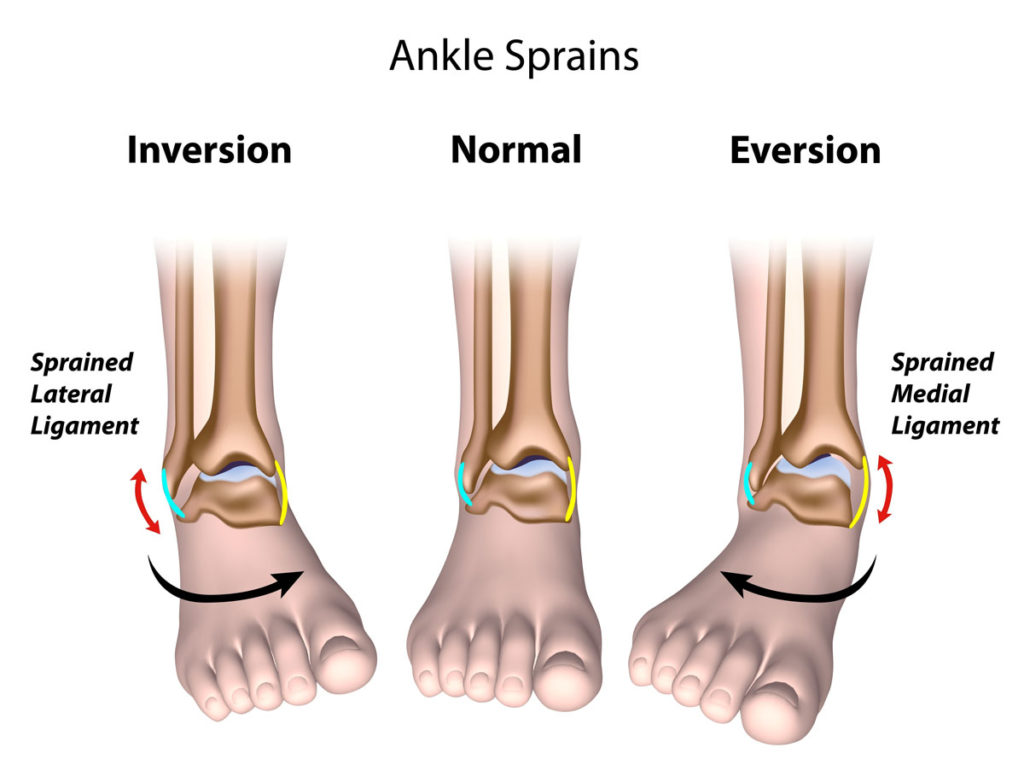

Lateral ankle sprains are often a result of an athlete planting and “rolling over” the outside of the foot. This results in micro or macroscopic tearing of the lateral ligament complex, often affecting the ankle joint cartilage, and possible bone related injury at high forces.

In the athletic population, for every 1000 athlete exposures (training session, game, performance), there is 1 athlete that will experience a lateral ankle injury. Medial and high ankle sprains are much less common. Of all ankle sprains, 3/4 are of the lateral ankle and 1/4 are of the medial or high ankle.

While data points towards “field sports” such as football, soccer and volleyball as high risk sports, ankle sprains can occur with participation in other athletic events including dance, judo, jiu jitsu and gymnastics.

The table below shows percentages of athletes within a specific sport that have chronic ankle instability and the percentage of athletes reporting a history of ankle pain.

Gender differences exist: females, are twice as likely to experience an ankle sprain. While the literature is unclear as to specific causes, several biomechanical, hormonal and musculoskeletal theories have been proposed, but are generally inconclusive.

It is interesting to note that very few people seek care from emergency care. This has been postulated to be due to most individuals being able to “get by” once the swelling and acute pain have subsided. Swelling often takes a week or 2 to resolve. A typical treatment approach for early intervention is the RICE method. Rest, Ice, compression & elevation. While this may help considerably in the short term, with most people can go about their daily routine, a large percentage (between 20-46%) will experience a subsequent injury within a year. Surveys demonstrate that 73% of athletes have sustained two sprains of the same ankle.

There have been algorithms that help medical professionals determine whether or not an athlete should have diagnostic imaging (x-rays) in an emergency situation. You can find that article HERE.

Reinjury rates vary between 20% (low) and 46% (high), depending on the level of activity, sport participation and other factors. Indeed, a previous ankle sprain is the biggest predictor for experiencing a subsequent sprain. Once injured, there is a 3.5x greater risk of experiencing a second ankle sprain.

Chronic ankle instability develops in about 70% of athletes after the first ankle sprain. This condition is described as a significant ankle sprain, feelings of instability or more than 2 episodes of giving way in the past 6 months.

Post-traumatic osteoarthritis may develop in the affected ankle as well. This is characterized by early degeneration of joint cartilage due to the high velocity trauma (acute), in addition to altered joint movement after the injury (chronic, repetitive). Because ankle sprains occur most often in youth and adolescent athletes, this may cause painful walking and participation in sports later on in life. Of all post-traumatic osteoarthritis cases of the ankle, 80% could be attributed to an ankle sprain earlier in life.

The good news is that there is plenty of research demonstrating that specific interventions can significantly reduce the risk of subsequent injury by 81%! Professional soccer teams that adopted the FIFA 11+ protocol were able to reduce lower extremity injury by 30%. With a 46% reinjury rate, athletes should be JUMPING at that opportunity. Given the post-injury complications, engaging in a quality program is well worth the investment if it means pursuing your passion.

Absolutely! I have helped hundreds of performing artists at Royal Caribbean and Celebrity cruises with many types of injuries. And performing artists are known for ankle injuries! Early intervention, coupled with confidence building and strength training exercises have helped high level athletes continue on with their career.

The most important thing is that a proper history, evaluation and program tailored to your specific goals are completed. Few physical therapists understand the commitment athletes make- sacrificing hanging out with friends to make practice. Sacrificing vacations to compete. I’ve been there and I’ve done that, now I want to help the next generation of athletes stay active and healthy.

A quick phone call will help determine what the best course of action for you is. We can set that up by having you call the number below.

The research we will discuss in this article focuses on 24 college aged athletes with a history of chronic ankle instability (CAI). Chronic ankle instability is classified as 1) History of significant ankle sprain 2) 2+ episodes of giving way in the past 6 months 3) Sensation of an unstable ankle. The runners were experienced, having run at least 20 miles/week for the past year. The runners with CAI were compared to a group of runners that did not have CAI. In this way, it could be determined what the difference between these two groups were.

Recent polls of collegiate and high school athletes suggest that about 25% experience CAI. Due to the high rate of reinjury and resulting dysfunction including time off from sport, specifically field sports such as soccer & football, studying the effects of CAI on running mechanics can help physical therapists improve outcomes for athletes. Our goal with physical therapy is to get athletes with ankle sprains back on the field at optimal performance and reduced injury risk. The literature suggests that between 40-70% of athletes will experience a second ankle sprain.

In this study, runners were placed on a treadmill and ground reaction forces were measured. The results demonstrate that peak forces and rate of loading (how fast the forefoot came into contact with the ground after heel strike) were significantly different between the runners in CAI group and non-CAI group. In effect, the runners experiencing CAI landed with a “stiffer” foot and ankle.

When an athlete experiences CAI, it seems to be that there is a significant change in movement patterns. These compensatory movement patterns place greater stress on the ankle joint and muscles. Previous research demonstrates poor muscle function of the ankle and hip muscles. This can be driven by attempts to avoid pain, or may be a subconscious adaptation to dysfunctional muscles.

Post-traumatic osteoarthritis may develop in the affected ankle as well. This is characterized by early degeneration of joint cartilage due to the high velocity trauma (acute), in addition to altered joint movement after the injury (chronic, repetitive). Because ankle sprains occur most often in youth and adolescent athletes, this may cause painful walking and participation in sports later on in life. Of all post-traumatic osteoarthritis cases of the ankle, 80% could be attributed to an ankle sprain earlier in life.

Absolutely! Specifically designed programs can “rewire” the brain and body to perform more efficiently. Progressively challenging exercises in a controlled environment can significantly improve confidence and facilitate quality movement for a safe return to sport.

Injury prevention programs have successfully reduced lower limb injury by up to 80%. Given that 74% of athletes experience a repeat ankle injury of the same ankle, an 80% reduction could make or break an athletes career.

A well-structured and progressive balance and strength training program can help bring you one step closer to the field.

If you are an athlete experiencing dysfunction due to an ankle sprain, we can help you recover and return to sport without medication and without surgery.

Give our office a call so we can help you get back to being an athlete!

The research we will discuss in this article focuses on 24 college aged athletes with a history of chronic ankle instability (CAI). Chronic ankle instability is classified as 1) History of significant ankle sprain 2) 2+ episodes of giving way in the past 6 months 3) Sensation of an unstable ankle. The runners were experienced, having run at least 20 miles/week for the past year. The runners with CAI were compared to a group of runners that did not have CAI. In this way, it could be determined what the difference between these two groups were.

Recent polls of collegiate and high school athletes suggest that about 25% experience CAI. Due to the high rate of reinjury and resulting dysfunction including time off from sport, specifically field sports such as soccer & football, studying the effects of CAI on running mechanics can help physical therapists improve outcomes for athletes. Our goal with physical therapy is to get athletes with ankle sprains back on the field at optimal performance and reduced injury risk. The literature suggests that between 40-70% of athletes will experience a second ankle sprain.

In this study, runners were placed on a treadmill and ground reaction forces were measured. The results demonstrate that peak forces and rate of loading (how fast the forefoot came into contact with the ground after heel strike) were significantly different between the runners in CAI group and non-CAI group. In effect, the runners experiencing CAI landed with a “stiffer” foot and ankle.

When an athlete experiences CAI, it seems to be that there is a significant change in movement patterns. These compensatory movement patterns place greater stress on the ankle joint and muscles. Previous research demonstrates poor muscle function of the ankle and hip muscles. This can be driven by attempts to avoid pain, or may be a subconscious adaptation to dysfunctional muscles.

Post-traumatic osteoarthritis may develop in the affected ankle as well. This is characterized by early degeneration of joint cartilage due to the high velocity trauma (acute), in addition to altered joint movement after the injury (chronic, repetitive). Because ankle sprains occur most often in youth and adolescent athletes, this may cause painful walking and participation in sports later on in life. Of all post-traumatic osteoarthritis cases of the ankle, 80% could be attributed to an ankle sprain earlier in life.

Absolutely! Specifically designed programs can “rewire” the brain and body to perform more efficiently. Progressively challenging exercises in a controlled environment can significantly improve confidence and facilitate quality movement for a safe return to sport.

Injury prevention programs have successfully reduced lower limb injury by up to 80%. Given that 74% of athletes experience a repeat ankle injury of the same ankle, an 80% reduction could make or break an athletes career.

A well-structured and progressive balance and strength training program can help bring you one step closer to the field.

If you are an athlete experiencing dysfunction due to an ankle sprain, we can help you recover and return to sport without medication and without surgery.

Give our office a call so we can help you get back to being an athlete!

In previous articles here, we discussed how ankle sprains can affect balance, walking and drop jumps. Other articles I wrote about ankle sprain epidemiology including reinjury rates and associated complications.

Now let’s turn to how ankle sprains affect running. If you are a runner experiencing pain, instability and dysfunction after an ankle sprain, this article should help you better understand how to treat ankle sprain and how ankle sprains affect running mechanics.

To summarize how walking is affected with chronic ankle instability due to ankle sprains:

The research we will discuss in this article focuses on 24 college aged athletes with a history of chronic ankle instability (CAI). Chronic ankle instability is classified as 1) History of significant ankle sprain 2) 2+ episodes of giving way in the past 6 months 3) Sensation of an unstable ankle. The runners were experienced, having run at least 20 miles/week for the past year. The runners with CAI were compared to a group of runners that did not have CAI. In this way, it could be determined what the difference between these two groups were.

Recent polls of collegiate and high school athletes suggest that about 25% experience CAI. Due to the high rate of reinjury and resulting dysfunction including time off from sport, specifically field sports such as soccer & football, studying the effects of CAI on running mechanics can help physical therapists improve outcomes for athletes. Our goal with physical therapy is to get athletes with ankle sprains back on the field at optimal performance and reduced injury risk. The literature suggests that between 40-70% of athletes will experience a second ankle sprain.

In this study, runners were placed on a treadmill and ground reaction forces were measured. The results demonstrate that peak forces and rate of loading (how fast the forefoot came into contact with the ground after heel strike) were significantly different between the runners in CAI group and non-CAI group. In effect, the runners experiencing CAI landed with a “stiffer” foot and ankle.

When an athlete experiences CAI, it seems to be that there is a significant change in movement patterns. These compensatory movement patterns place greater stress on the ankle joint and muscles. Previous research demonstrates poor muscle function of the ankle and hip muscles. This can be driven by attempts to avoid pain, or may be a subconscious adaptation to dysfunctional muscles.

Post-traumatic osteoarthritis may develop in the affected ankle as well. This is characterized by early degeneration of joint cartilage due to the high velocity trauma (acute), in addition to altered joint movement after the injury (chronic, repetitive). Because ankle sprains occur most often in youth and adolescent athletes, this may cause painful walking and participation in sports later on in life. Of all post-traumatic osteoarthritis cases of the ankle, 80% could be attributed to an ankle sprain earlier in life.

Absolutely! Specifically designed programs can “rewire” the brain and body to perform more efficiently. Progressively challenging exercises in a controlled environment can significantly improve confidence and facilitate quality movement for a safe return to sport.

Injury prevention programs have successfully reduced lower limb injury by up to 80%. Given that 74% of athletes experience a repeat ankle injury of the same ankle, an 80% reduction could make or break an athletes career.

A well-structured and progressive balance and strength training program can help bring you one step closer to the field.

If you are an athlete experiencing dysfunction due to an ankle sprain, we can help you recover and return to sport without medication and without surgery.

Give our office a call so we can help you get back to being an athlete!

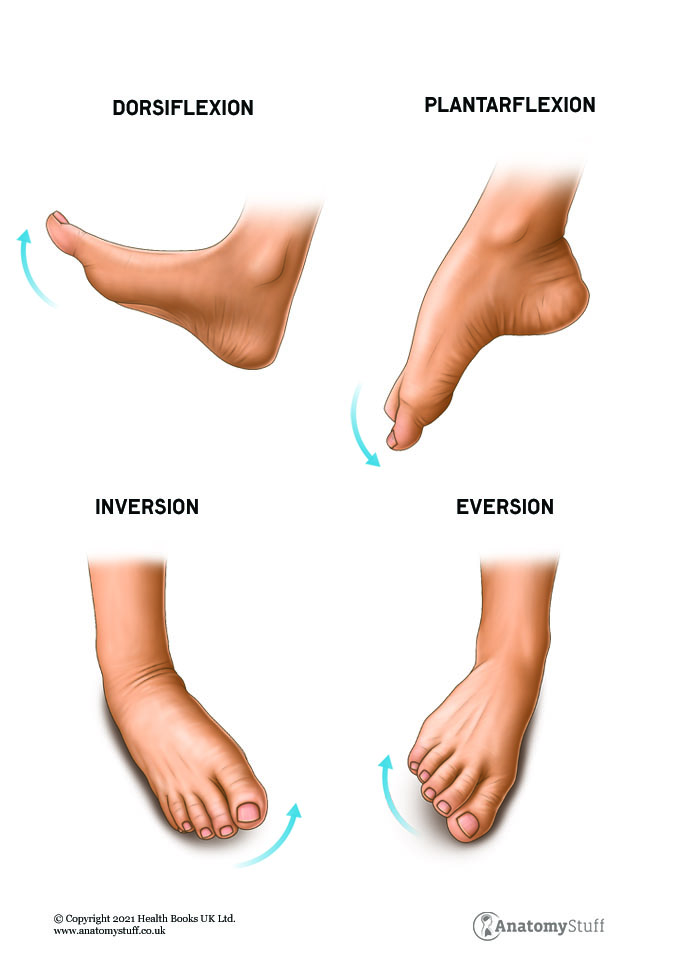

Three bones form the ankle joint: tibia, fibula and the talus. There are 4 main movements at the ankle: dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, inversion & eversion.

The joint is stabilized by three main groups of ligaments. The ligaments provide support on the medial (inside), lateral (outside) of the ankle and between the tibia and fibula bones. The ligaments prevent excessive motion, provide joint stability and act to create leverage for movement.

The anterior talofibular ligament provides support laterally. The ligament prevents the foot from inverting, or pointing inward. This ligament is typically injured when the ankle “rolls in”.

The interosseous membrane, anterior and posterior tibiofibular ligaments support the “upper ankle”. The membrane forms a web that spans the space between the tibia and fibular bones, whereas the tibiofibular ligaments are located closer to the ankle joint.

The posterior tibiotalar, tibiocalcaneal, tibionavicular and anterior tibiotalar ligament provide support medially. This group of ligaments collectively prevent the foot from everting, or pointing outwards. These ligaments are injured when the ankle “rolls out”. They are rarely injured since they are very strong.

There are four main groups of muscles that control the foot and ankle. The muscles located on the outside (lateral) and inside (medial) part of the lower leg control inversion and eversion, or the toes pointing inward or outward. The muscles on the front and back of the lower leg control dorsiflexion and plantarflexion.

The muscles work in synergy to provide effective and efficient movement.

Taken as a whole, athletes participating in sport that present with signs and symptoms suggestive of EDS or other hypermobile syndromes, should have a comprehensive evaluation including joint mobility, muscular strength, balance and coordination, in addition to systemic issues including gastrointestinal, cardiology, psychiatry and neurology. The relative muscular weakness of athletes presenting with EDS and hypermobile syndromes may require additional time or effort to improve strength to be able to perform well and reduce injury risk. The good news is that strength training has a protective effect on joints, improves pain experience and reduces the risk of fall-related injuries. It is imperative that the athlete and their trainers keep an eye on fatigue levels, as individuals with EDS tend to fatigue earlier compared to their non-EDS peers. If athletes with EDS are managing an injury, it is usually best to continue activity with modifications, rather than completely stop.

While EDS and hypermobile syndromes are highly prevalent in the performing arts community, awareness of the associated complications and injury-risk factors is not fully understood with all health care providers. Seeking physical therapy treatment from a therapist that understands the physical and emotional demands of performing arts in addition to complications with EDS can make an enormous difference in an athletes career.

If you are an athlete experiencing EDS or hypermobility, and are concerned about returning to sport, give our office a call. Dr. Abbate has years of experience helping hundreds of professional performing artists at Royal Caribbean and Celebrity Cruises. If he can help them, he can help you!

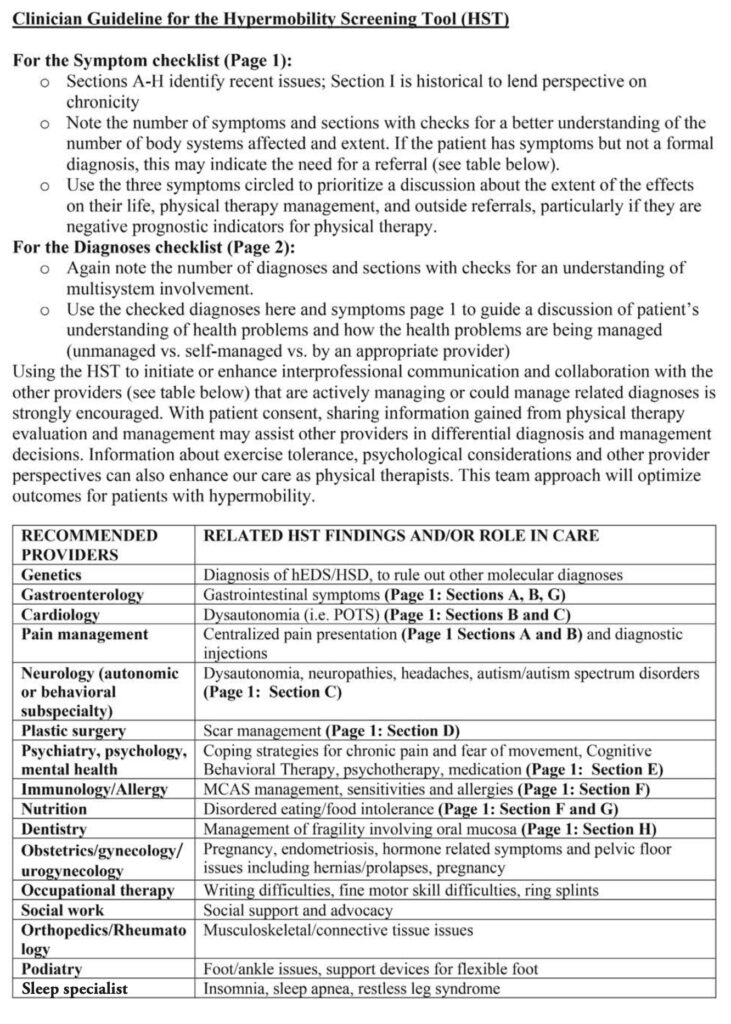

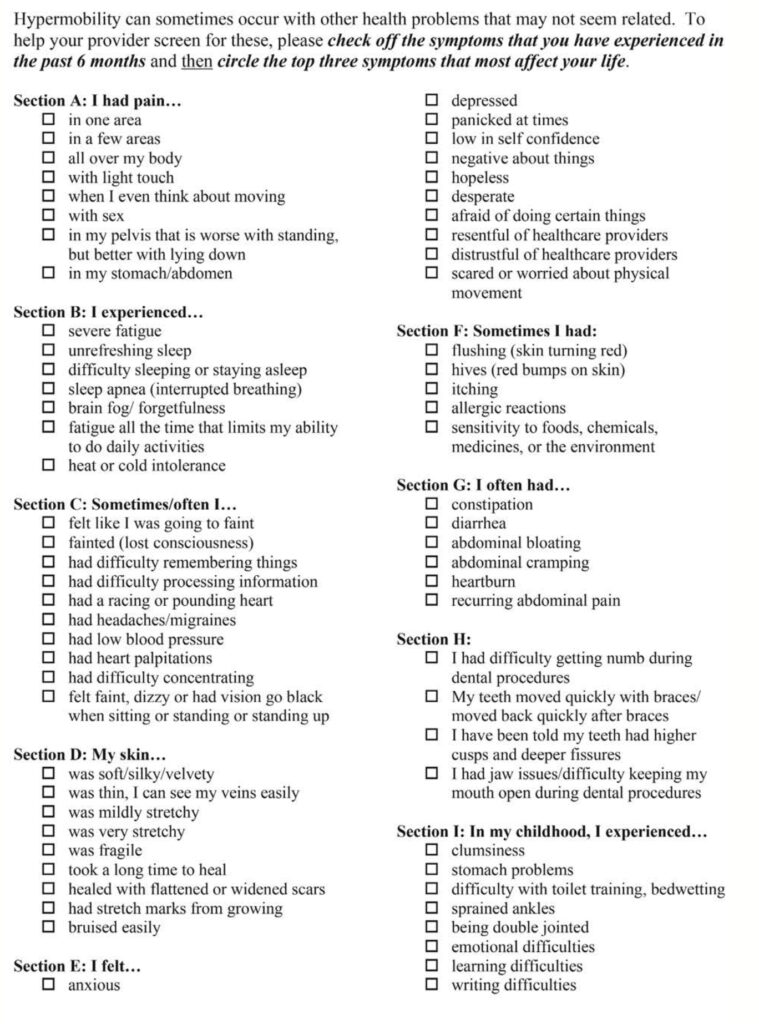

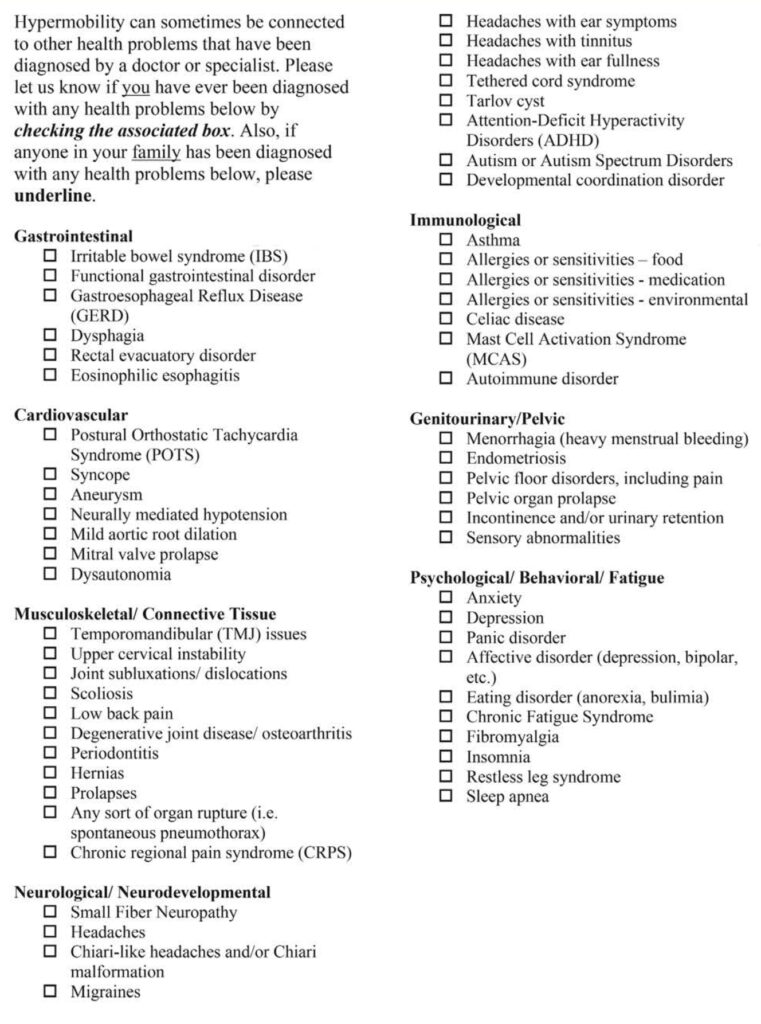

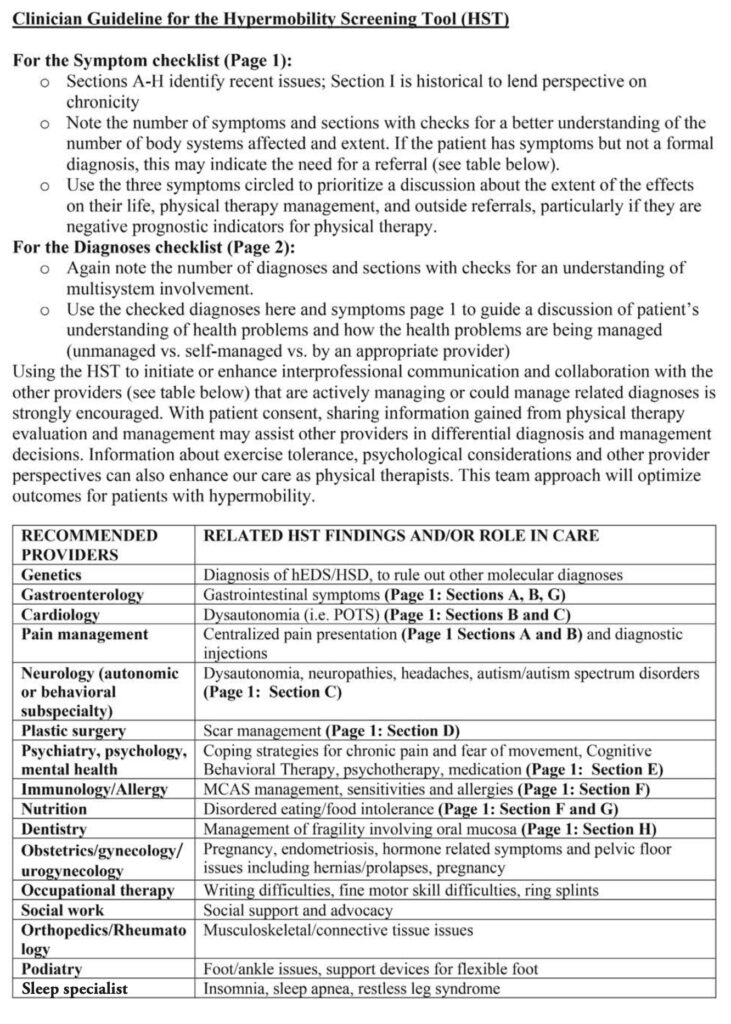

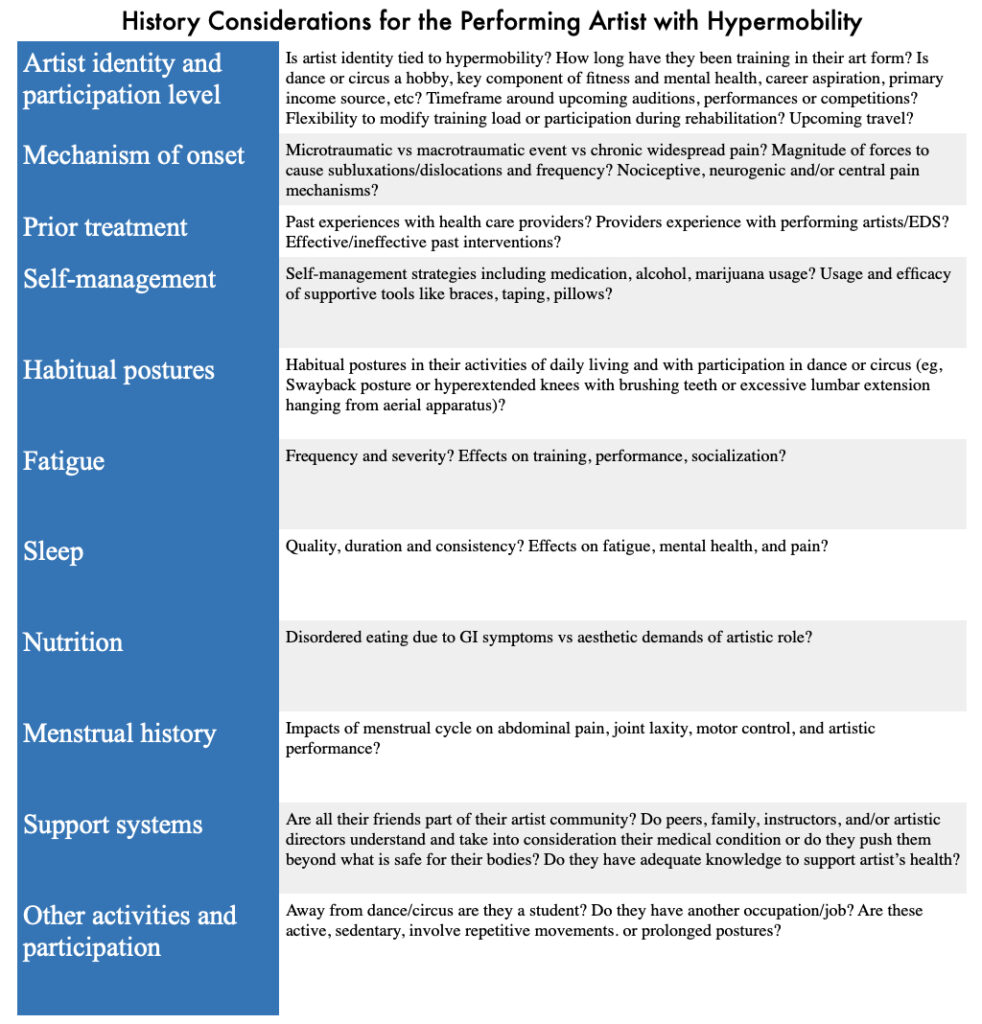

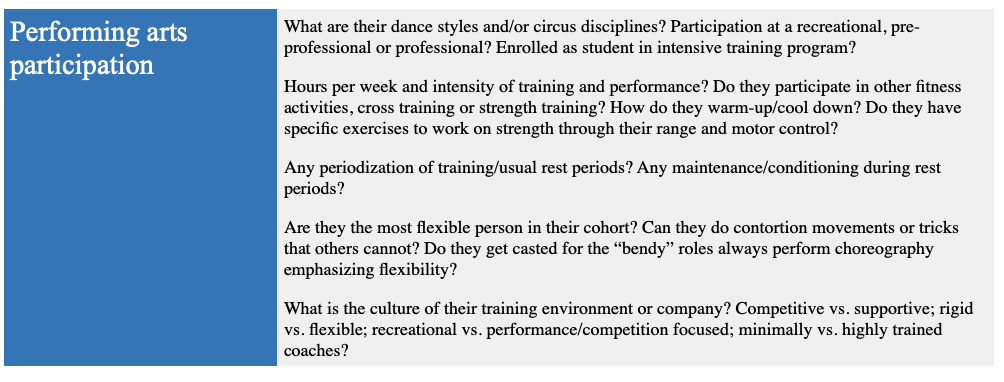

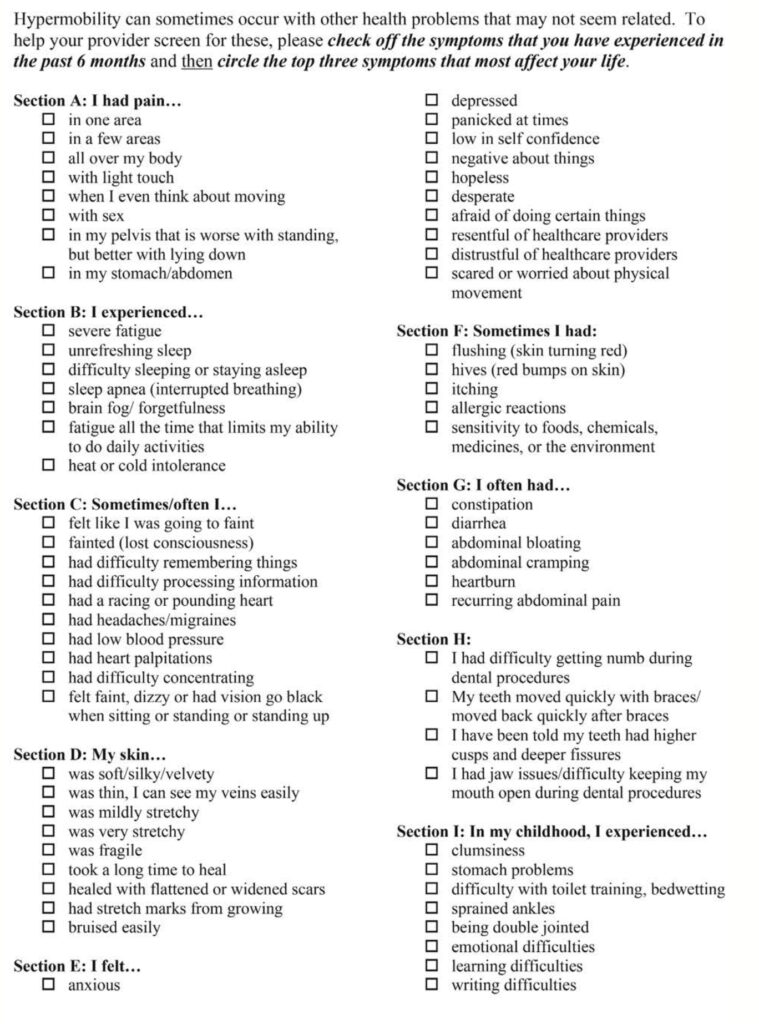

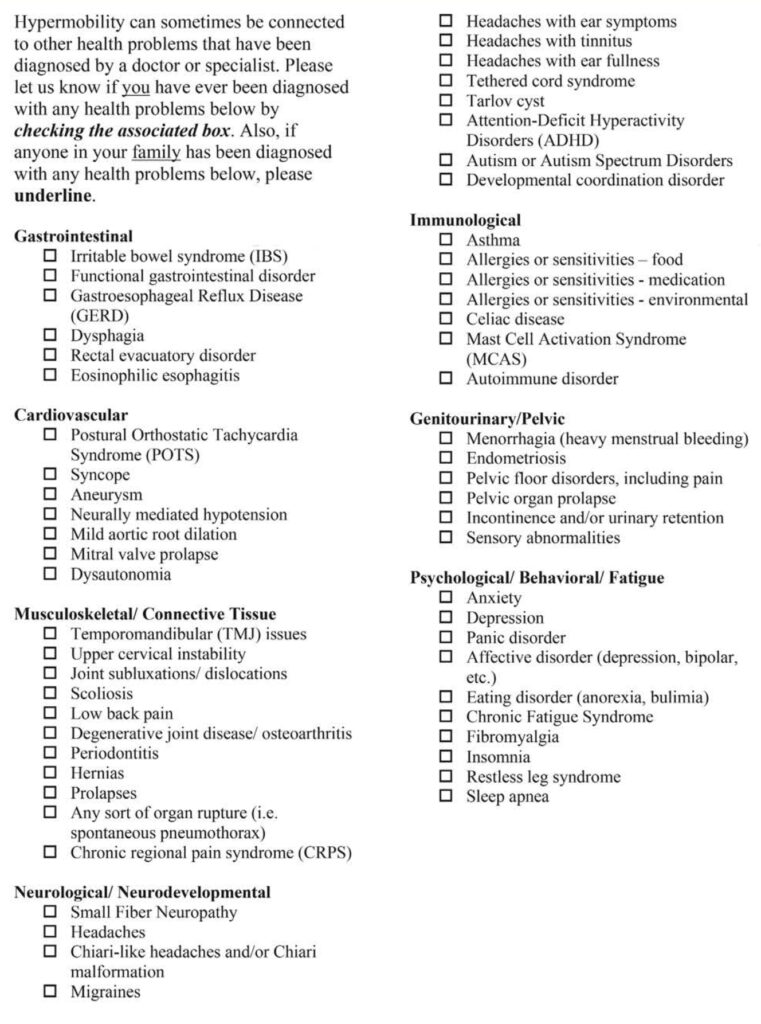

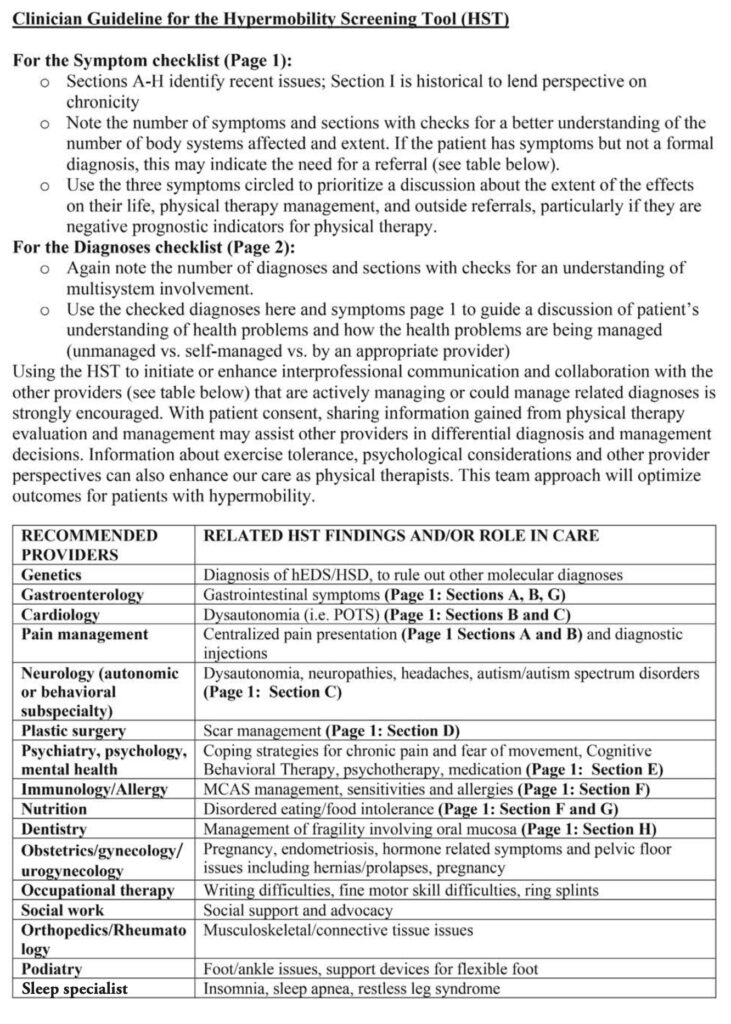

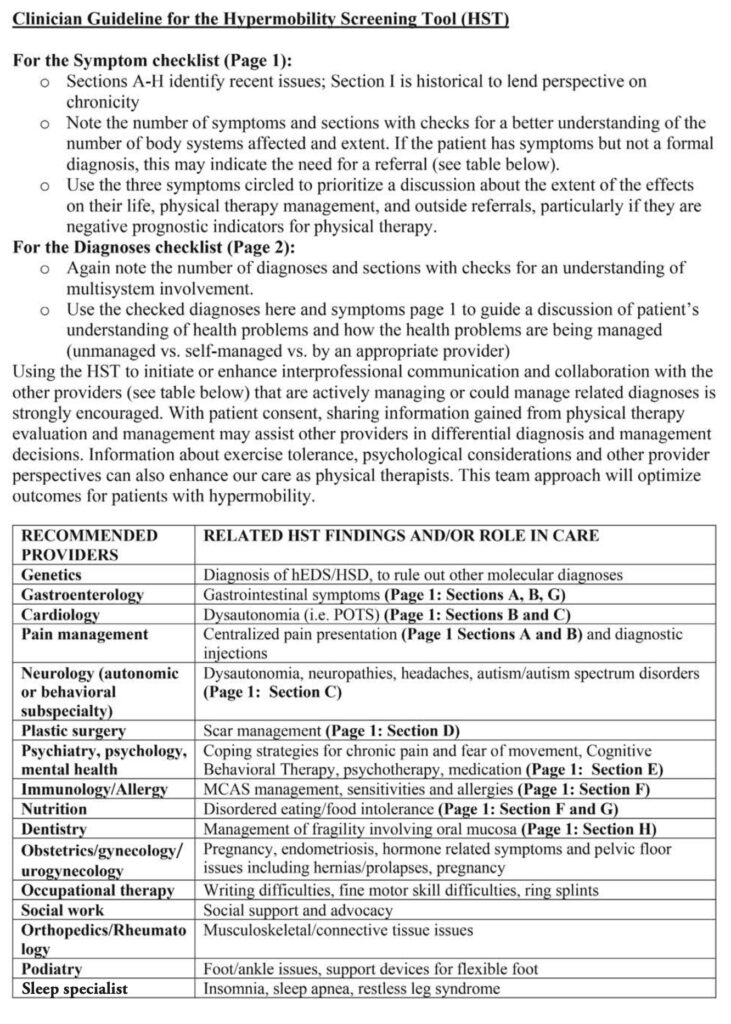

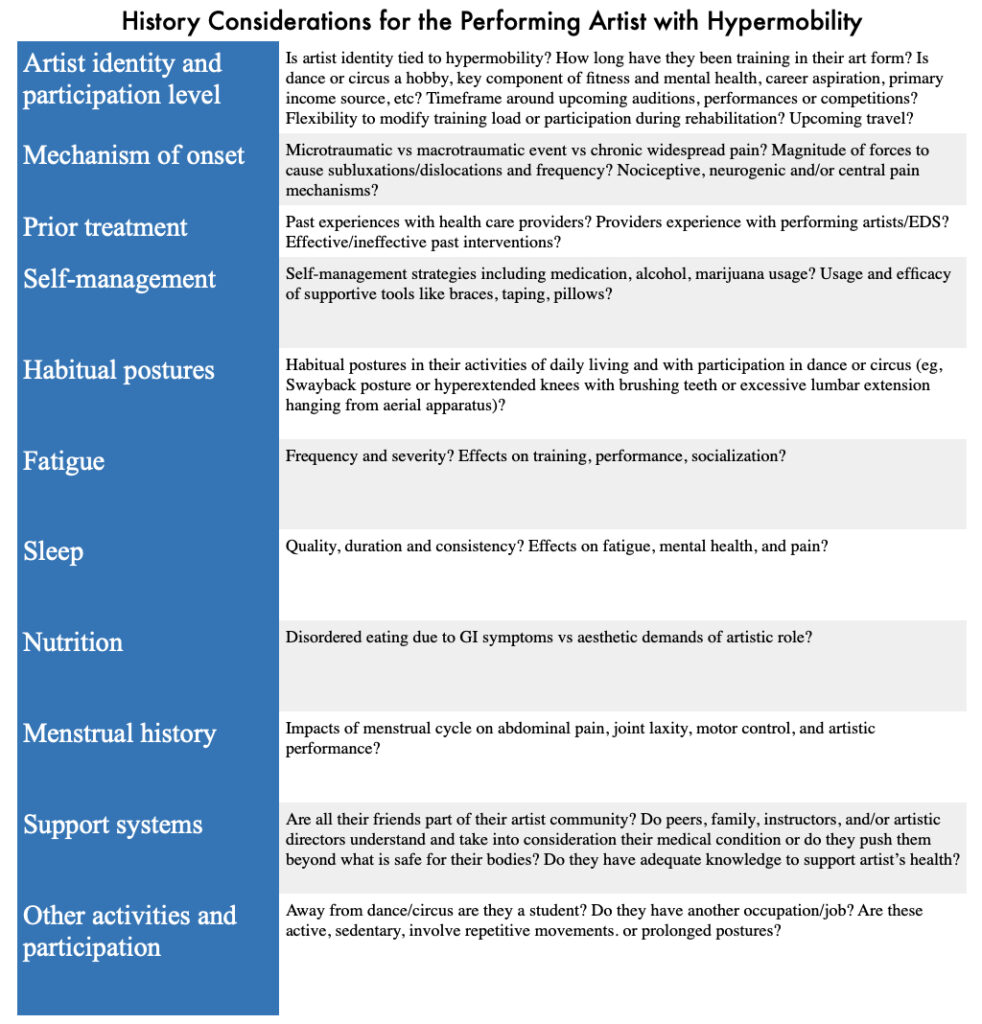

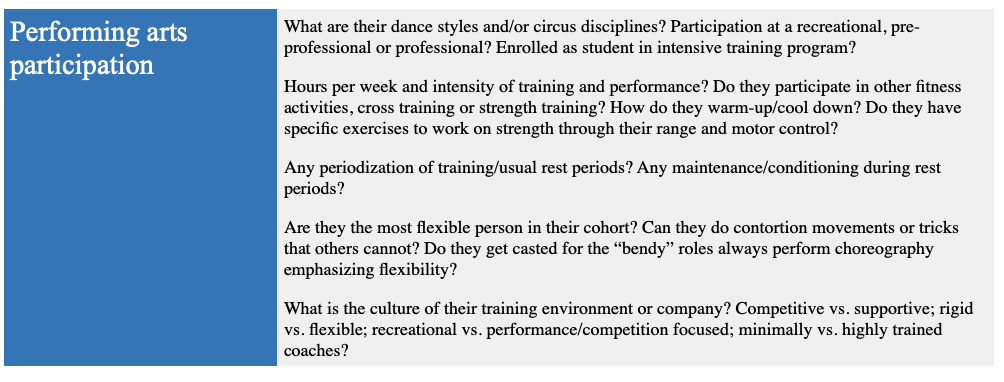

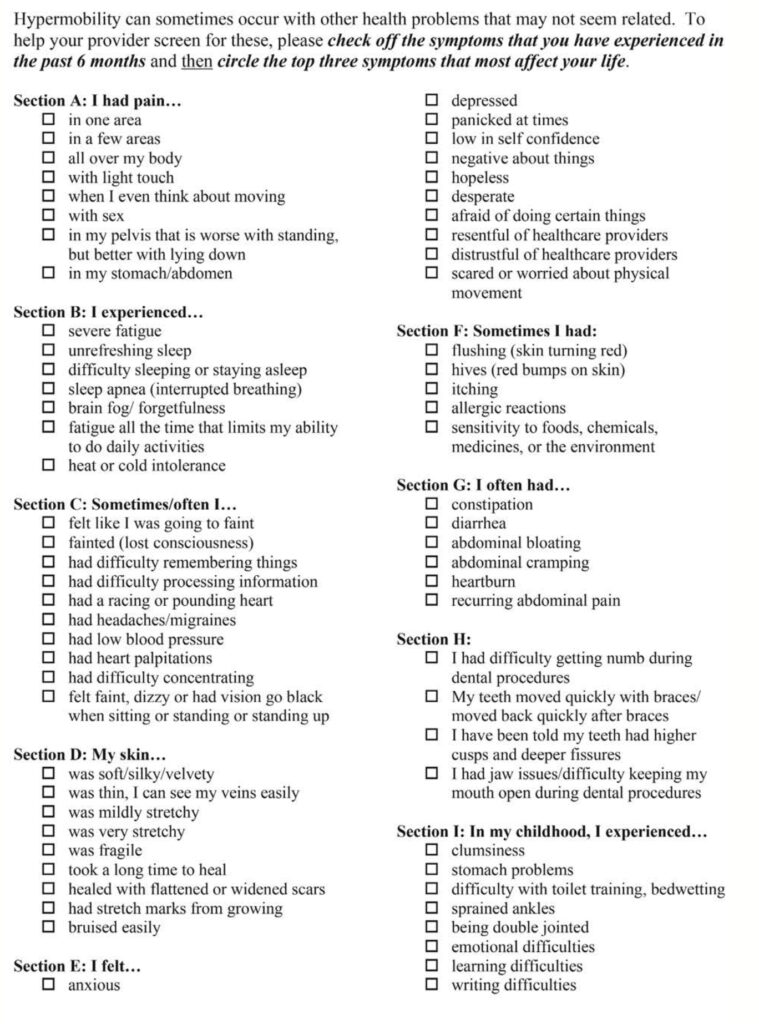

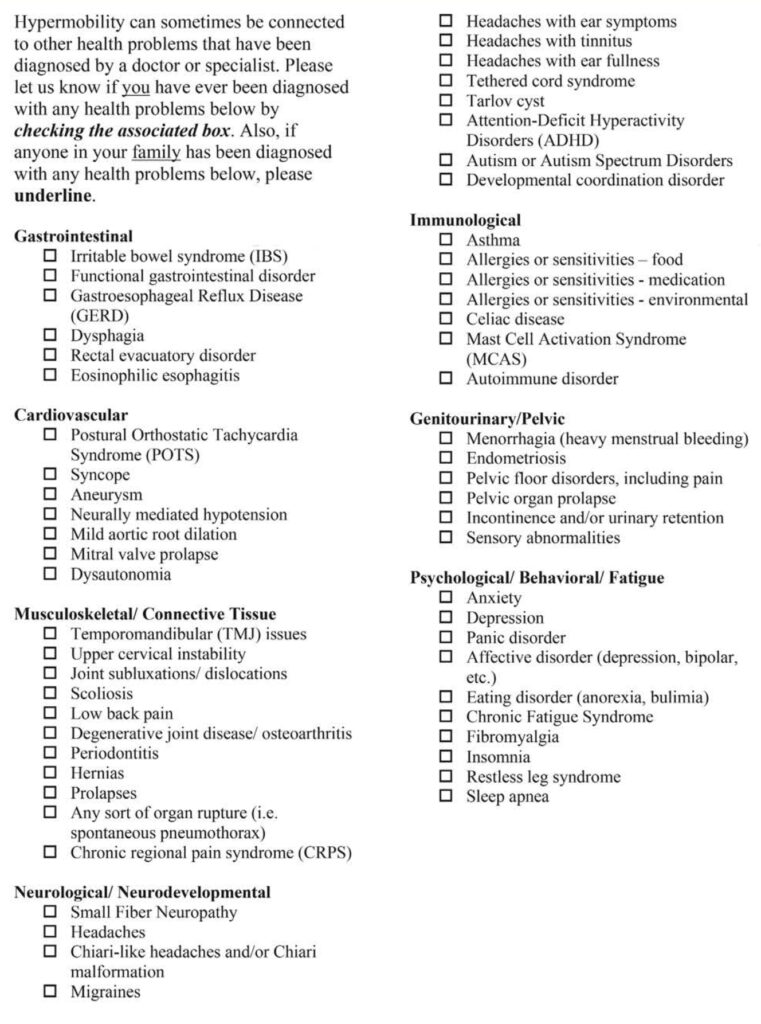

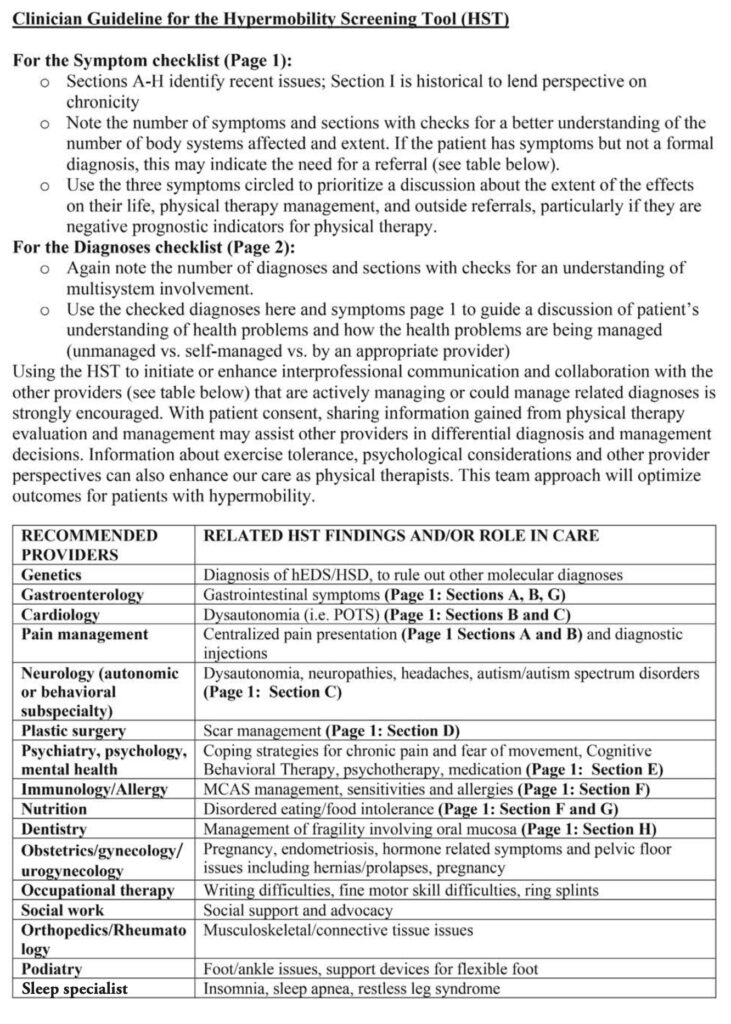

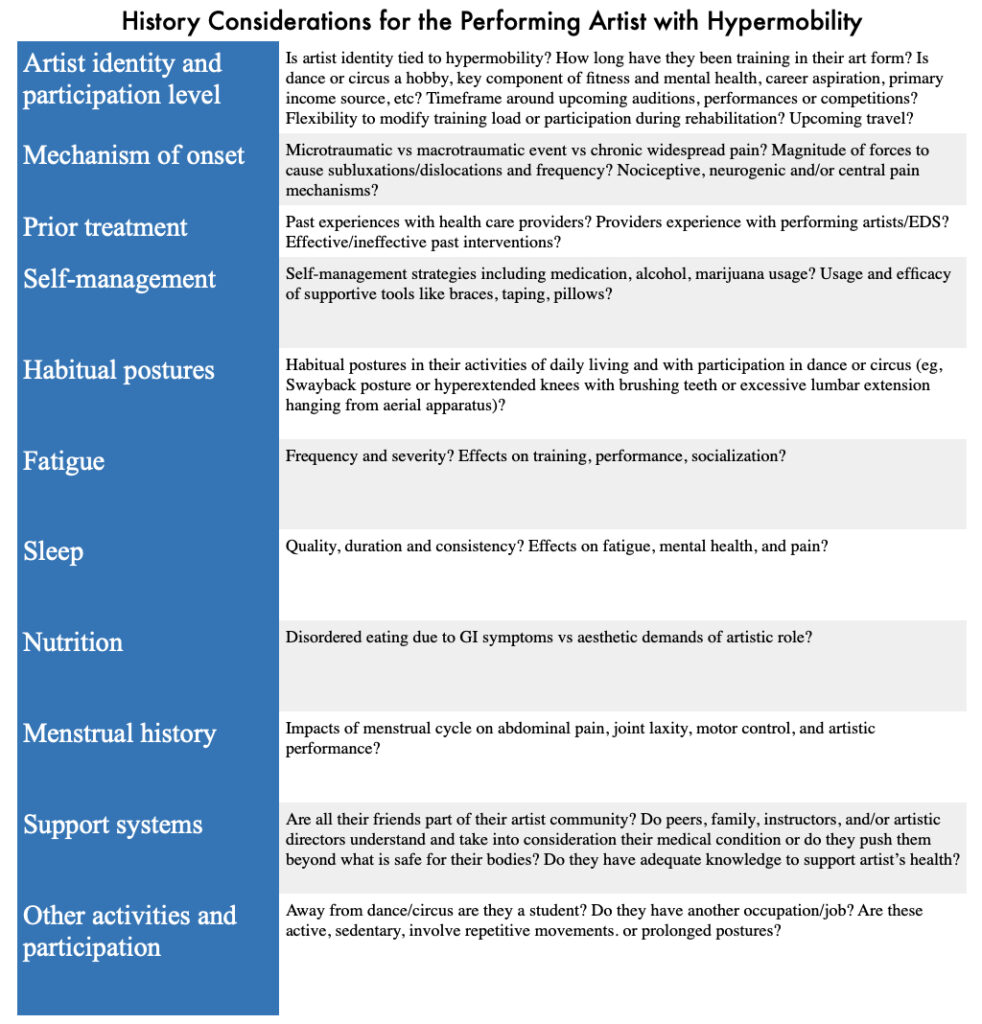

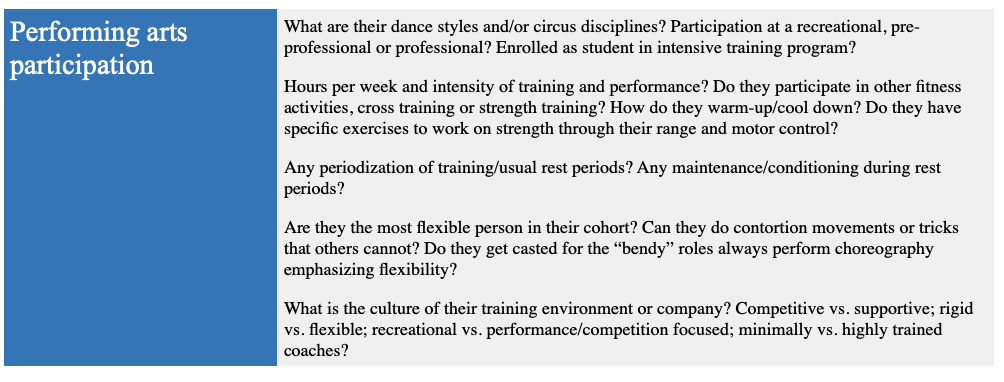

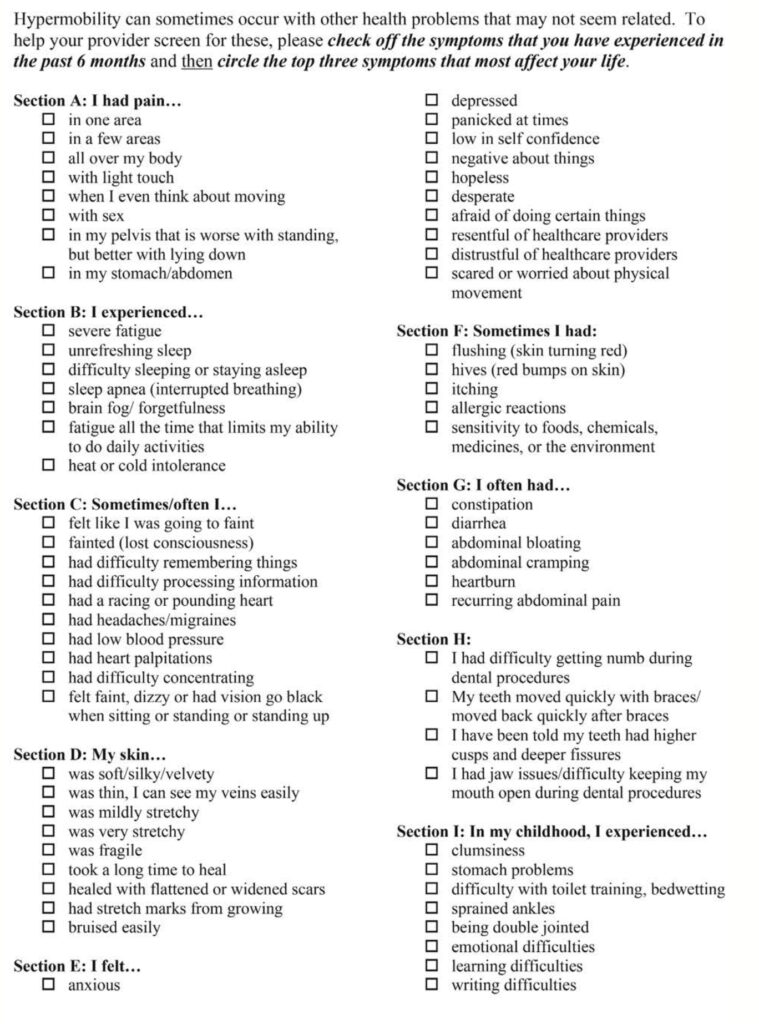

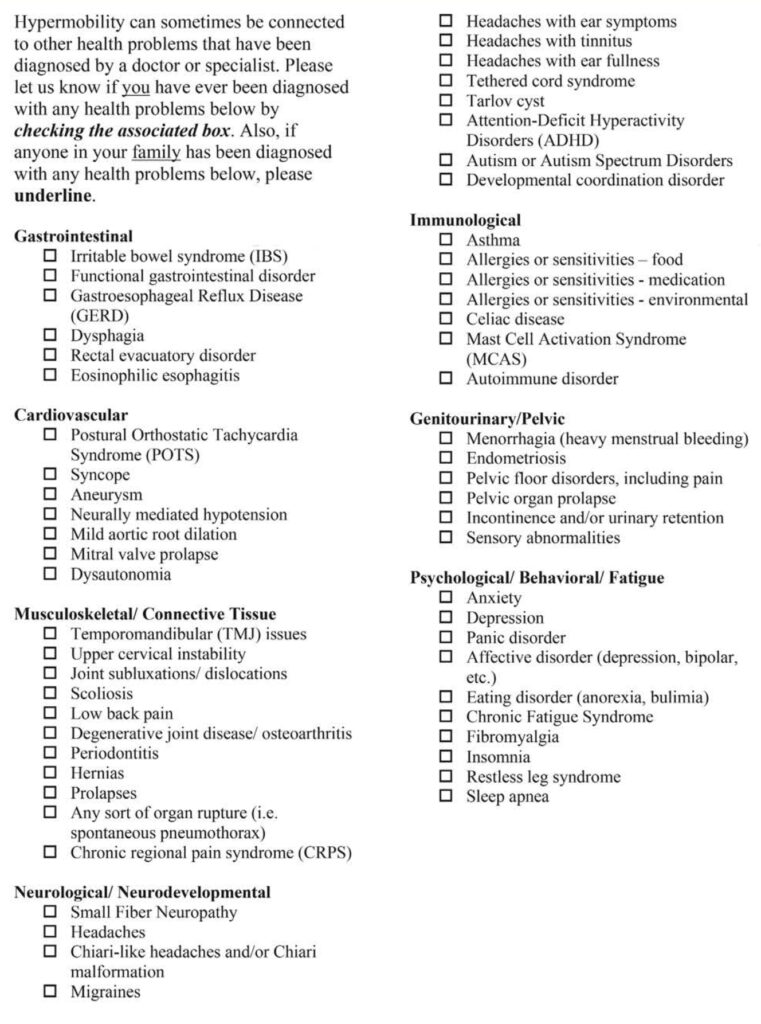

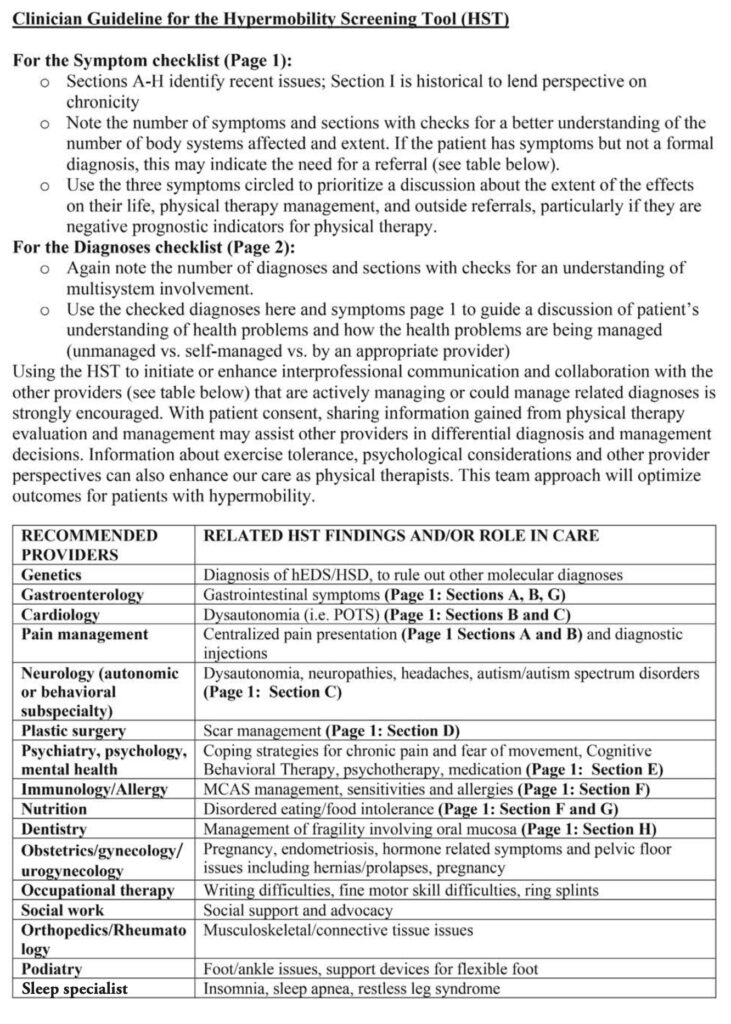

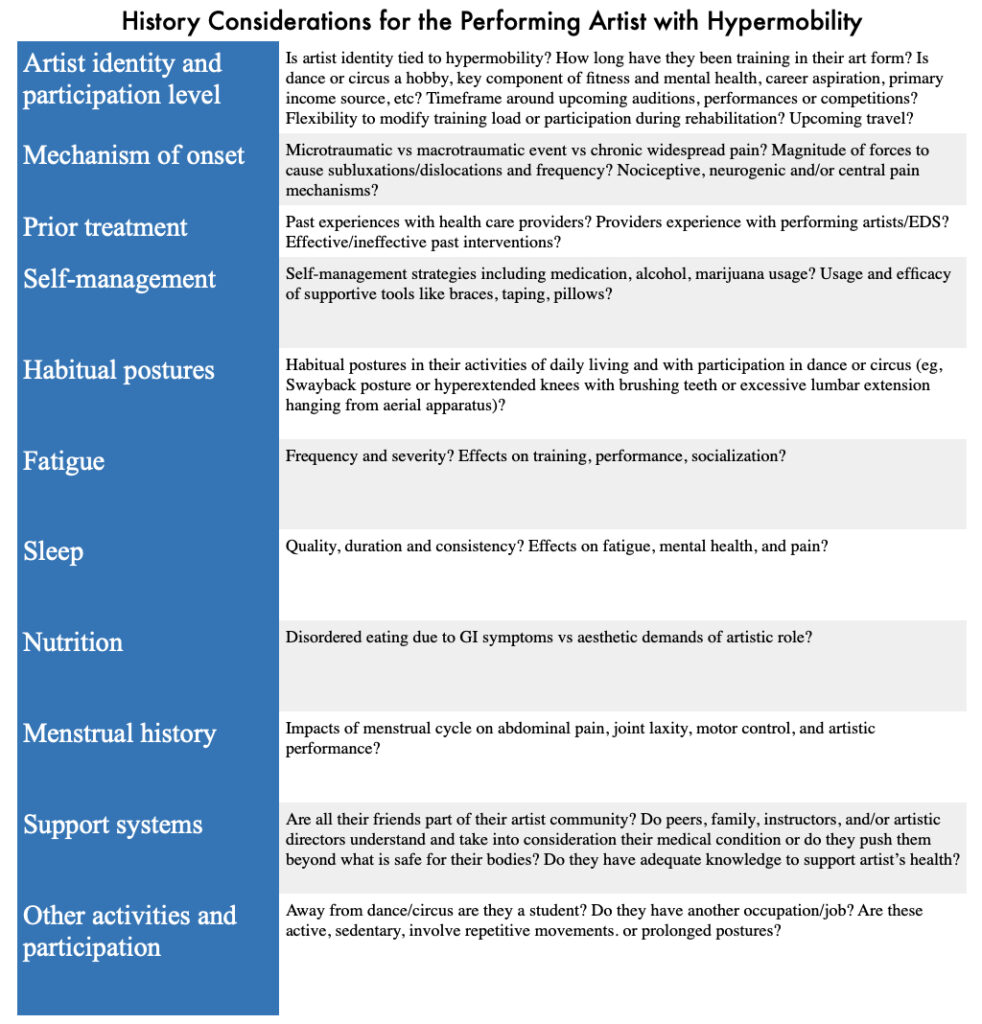

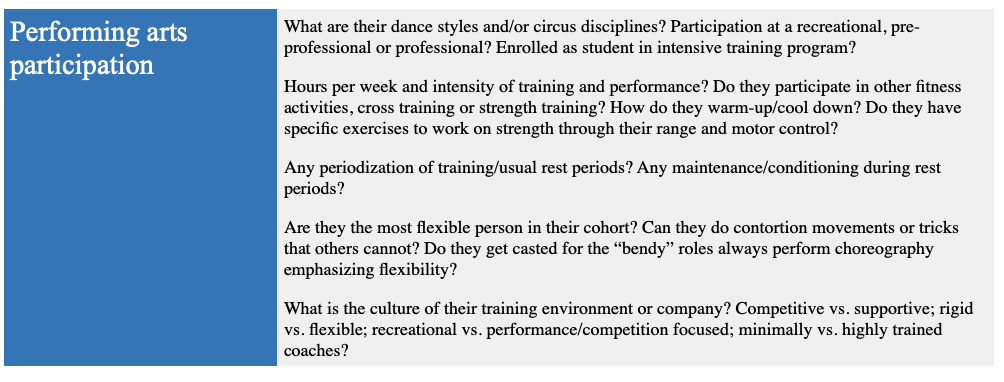

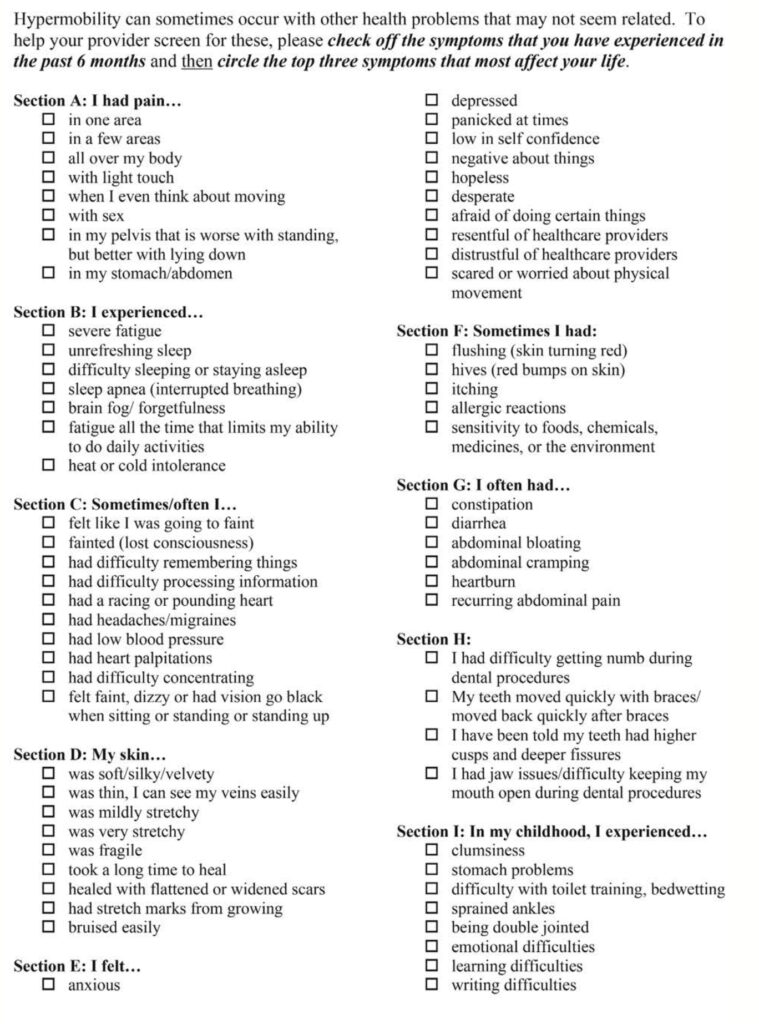

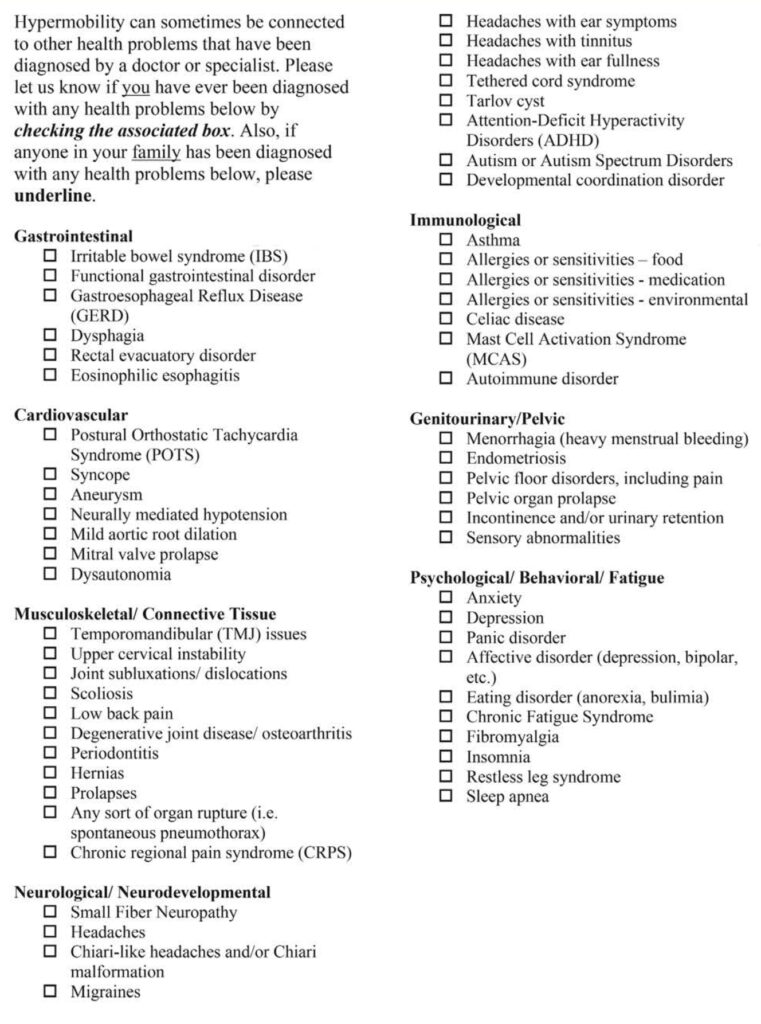

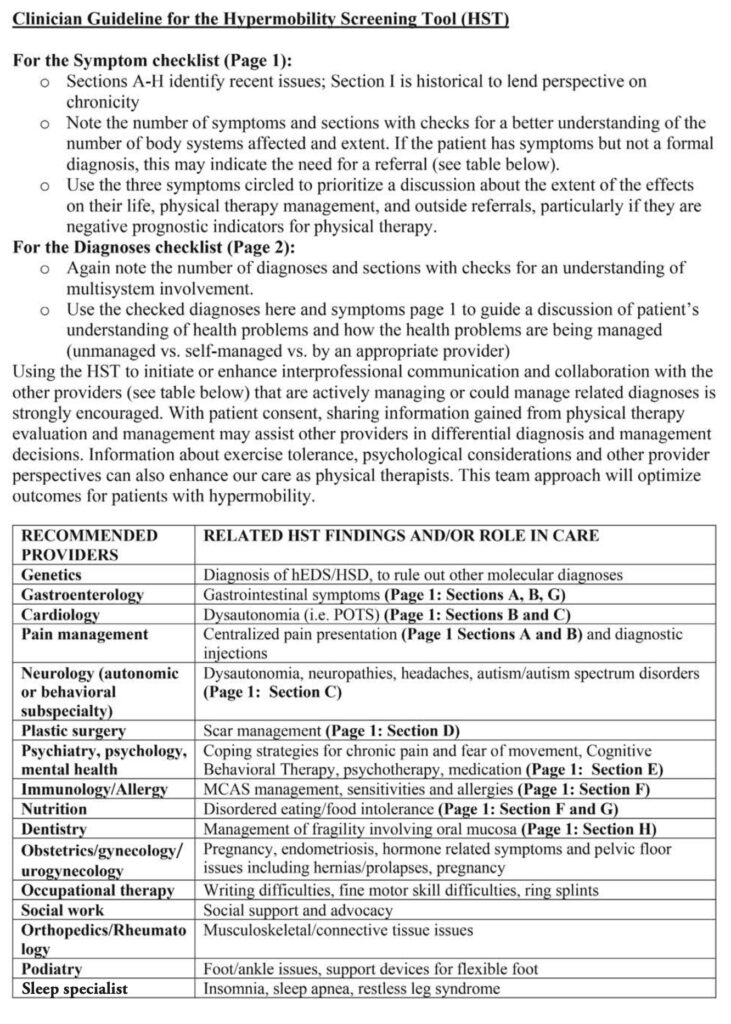

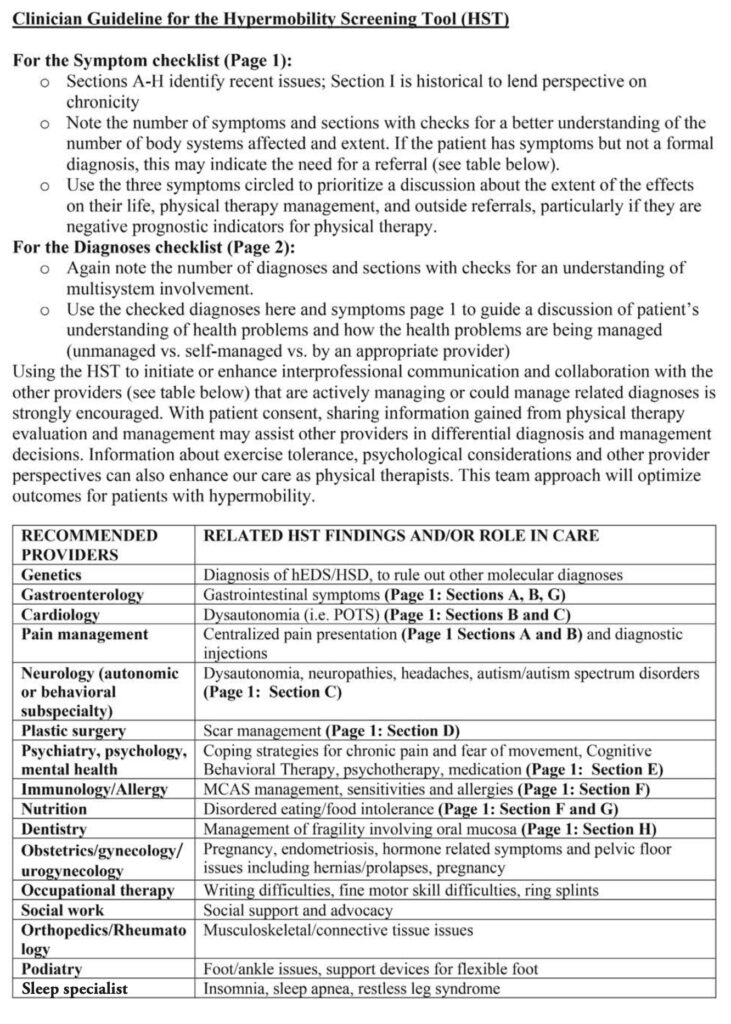

There are several physical and historical screens that a physical therapist can administer. The Hypermobility Screening Tool can assist therapists in identifying systems-related dysfunction, and allow for proper referral to a health care provider. For example, an athlete complaining of headaches or dizziness with changes in body position, or after participating in strenuous activity, may warrant referral to a cardiologist. An athlete reporting frequent ankle sprains may require referral to an orthopedic.

The Beighton Score, Brighton criteria and 5-point screening questionnaire can be used to screen for joint hypermobility. These scoring systems identify joints that have excessive flexibility. It helps physical therapists identify which body parts need continued observation or focused intervention to prevent an injury from occurring. Other tests may include muscle function (strength and endurance) and balance (joint stability plays an important role in posture).

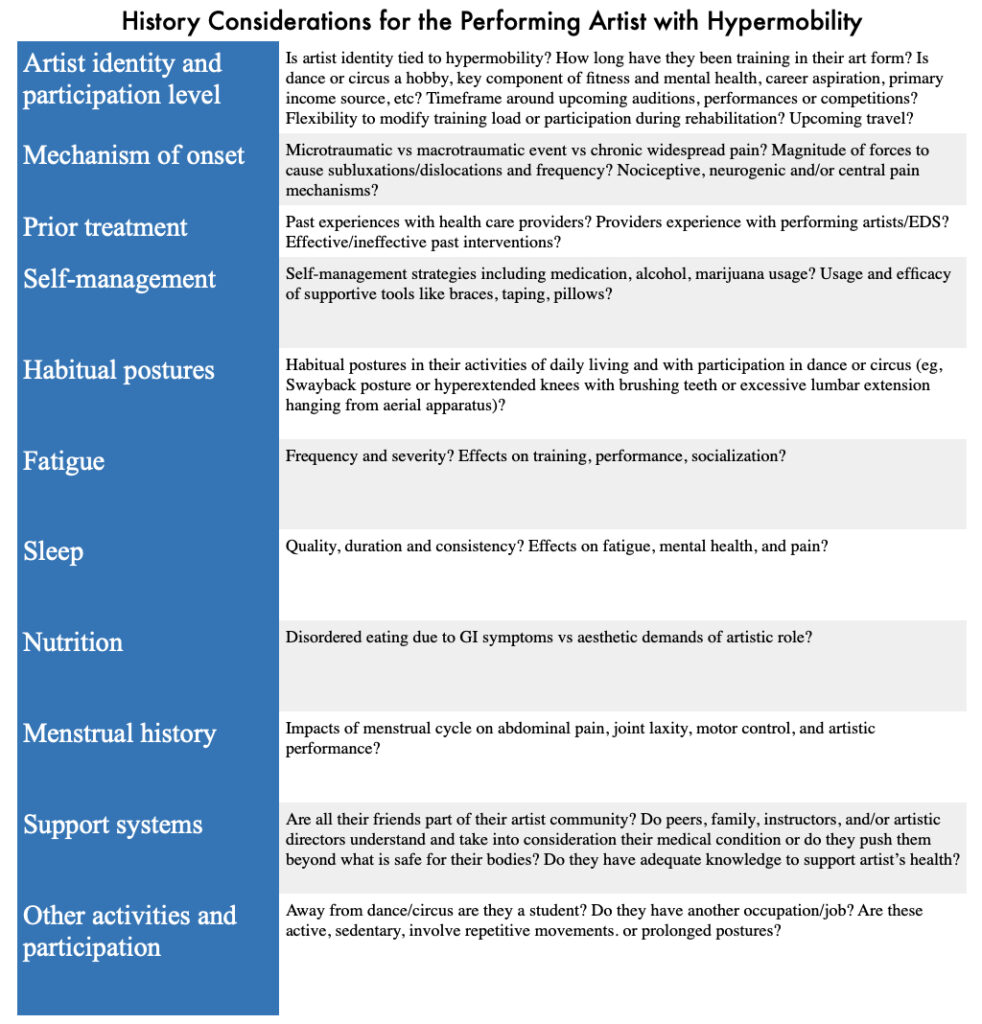

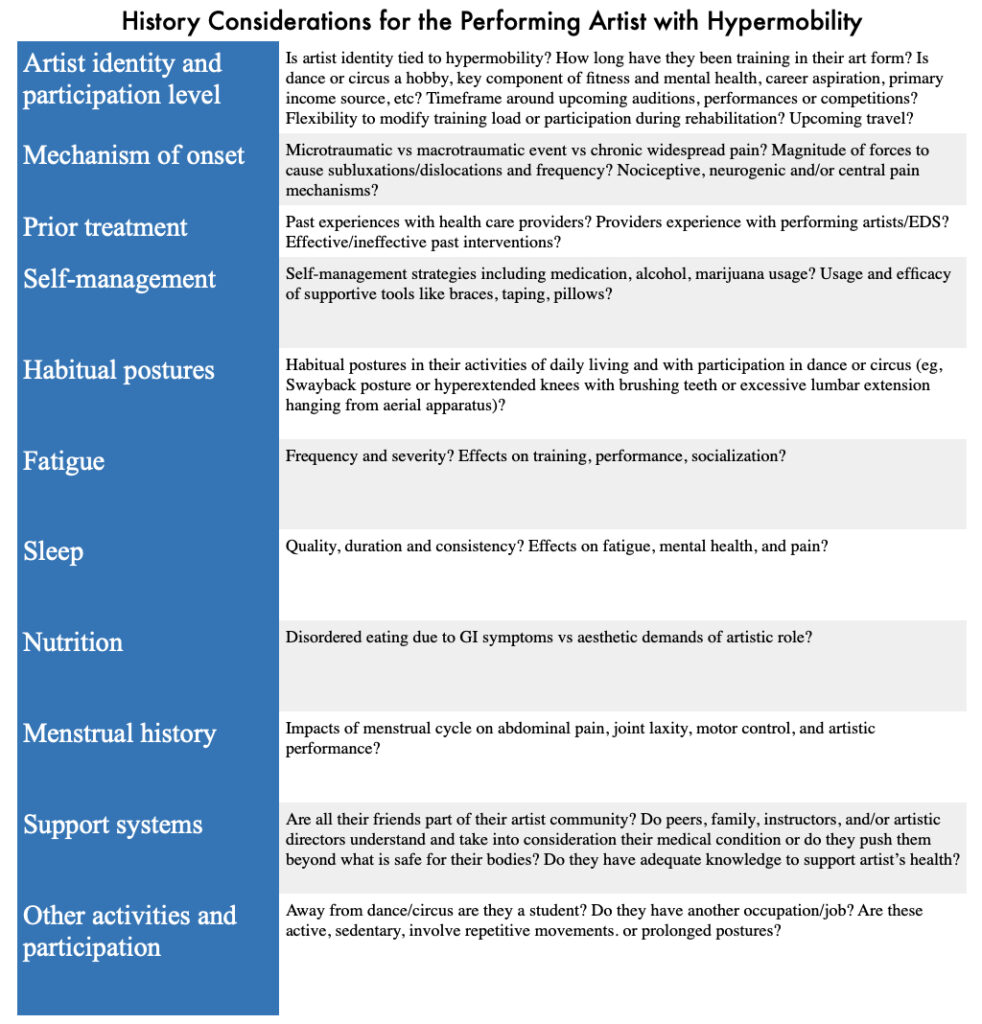

Below is a chart describing the types of tests physical therapists can utilize to help athletes experiencing symptoms of EDS.

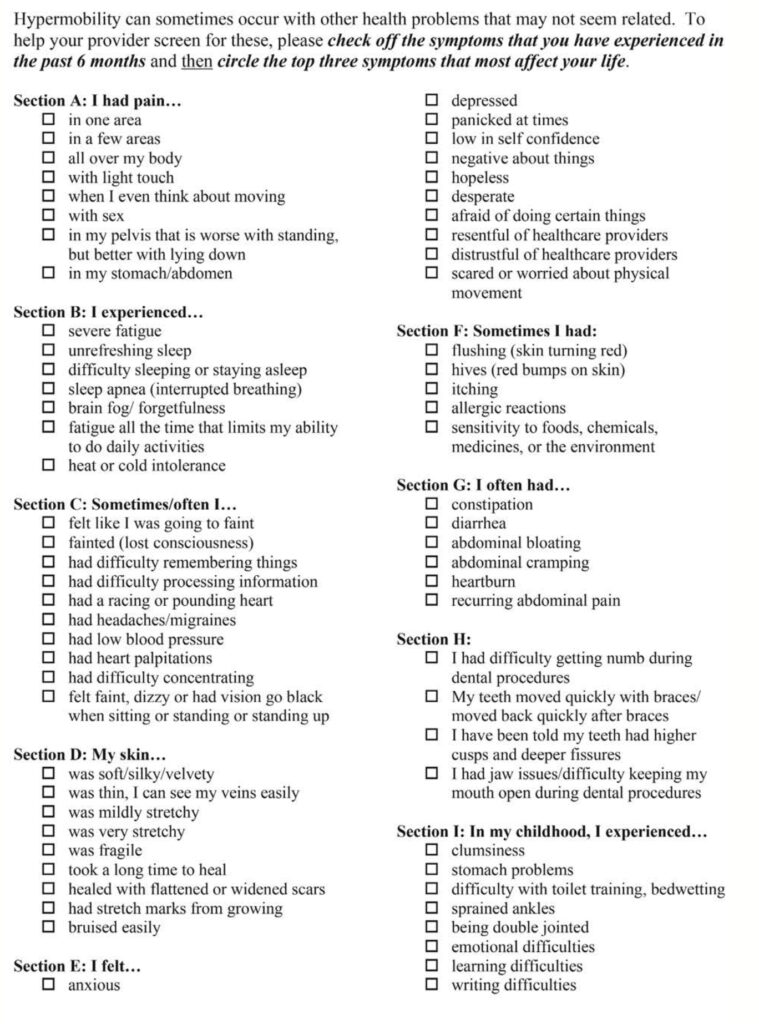

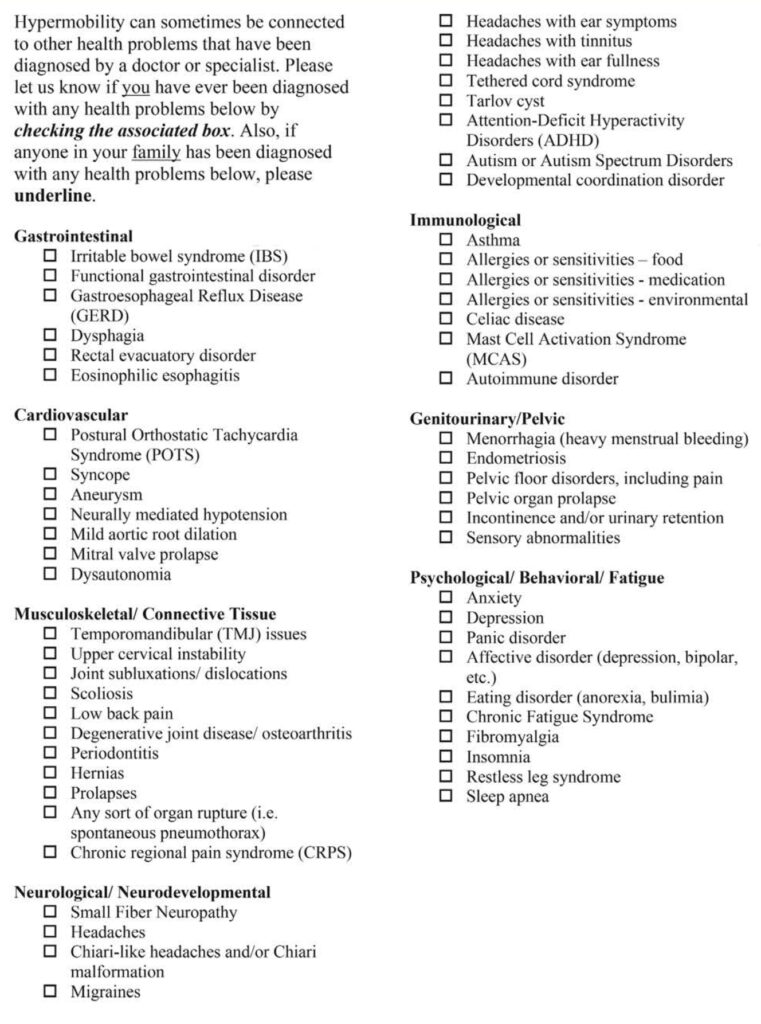

Athletes participating in sports that are seeking medical attention for pain or weakness often complete screening tools. These screening tools can help facilitate referral to a proper medical provider, or help direct treatment by a physical therapist. It also provides a kind of “journal” for an athlete to measure over a specific time period. By keeping record of the day and symptoms, an athlete can visualize over the course of treatment what their symptoms are at any given time frame.

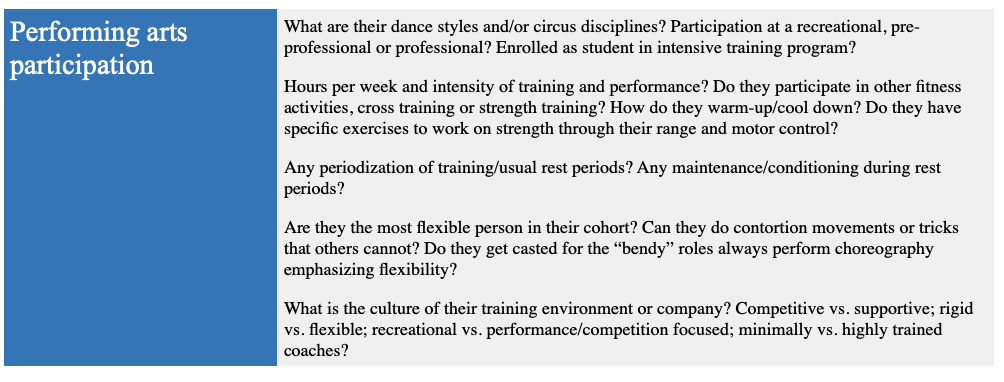

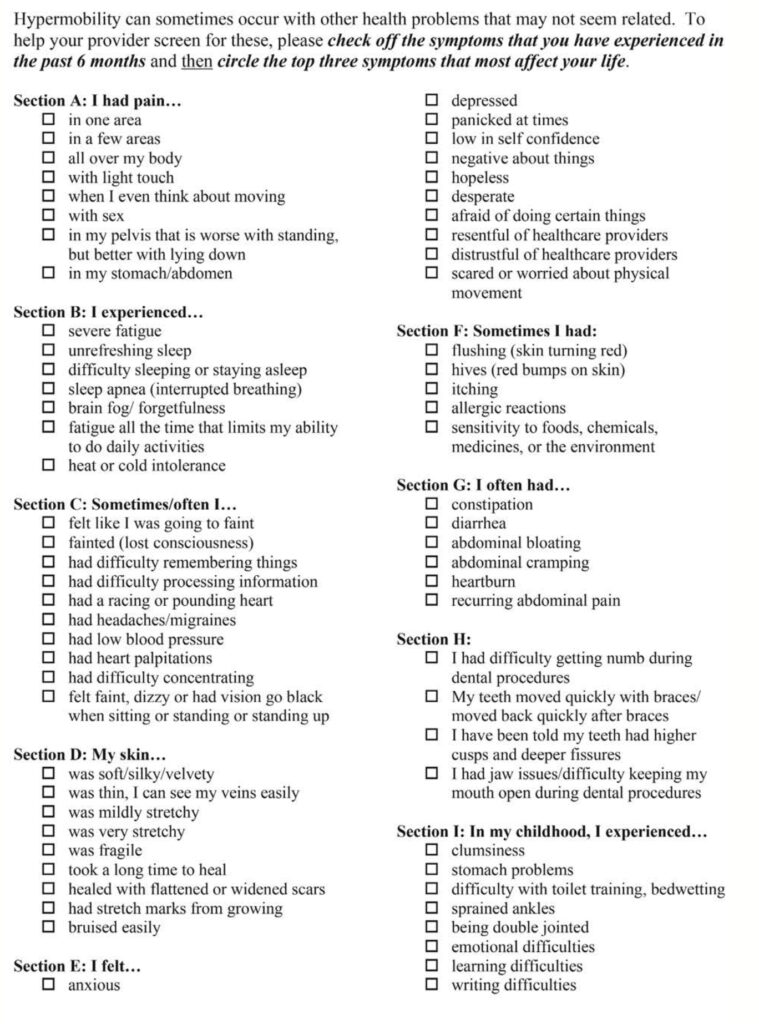

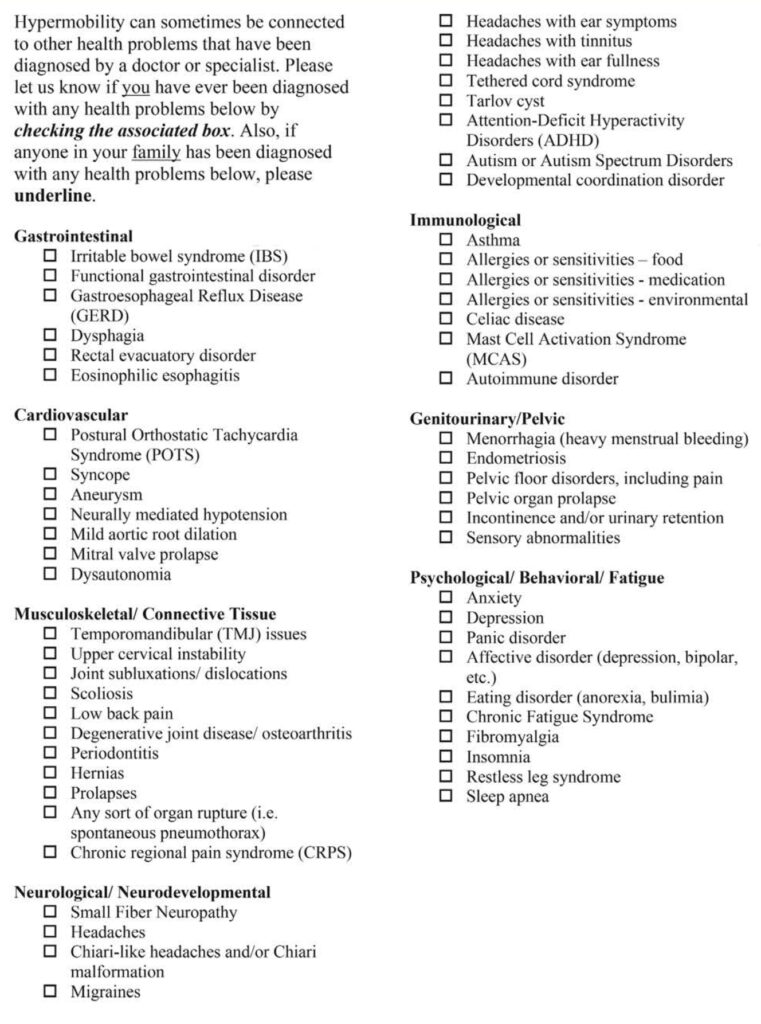

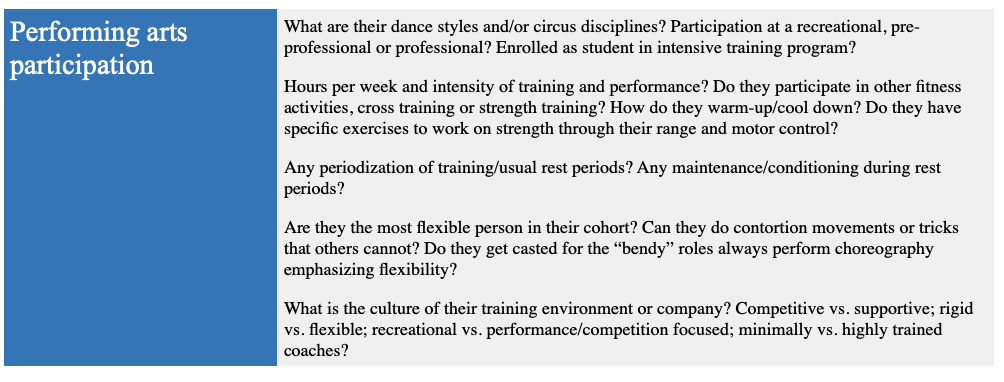

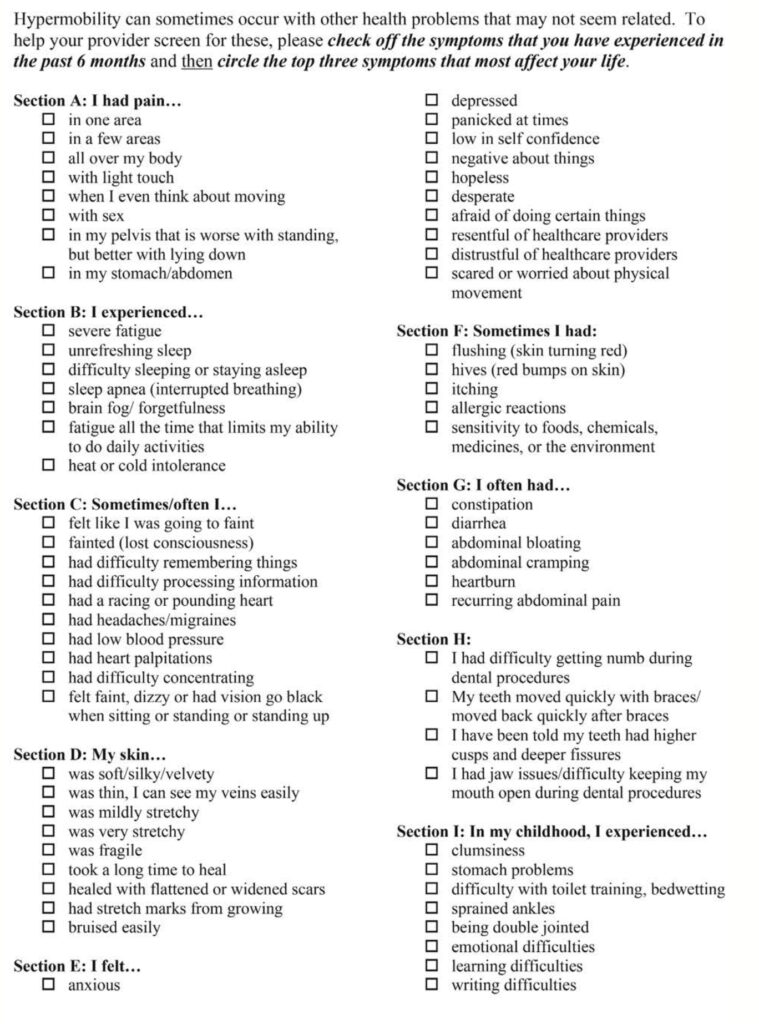

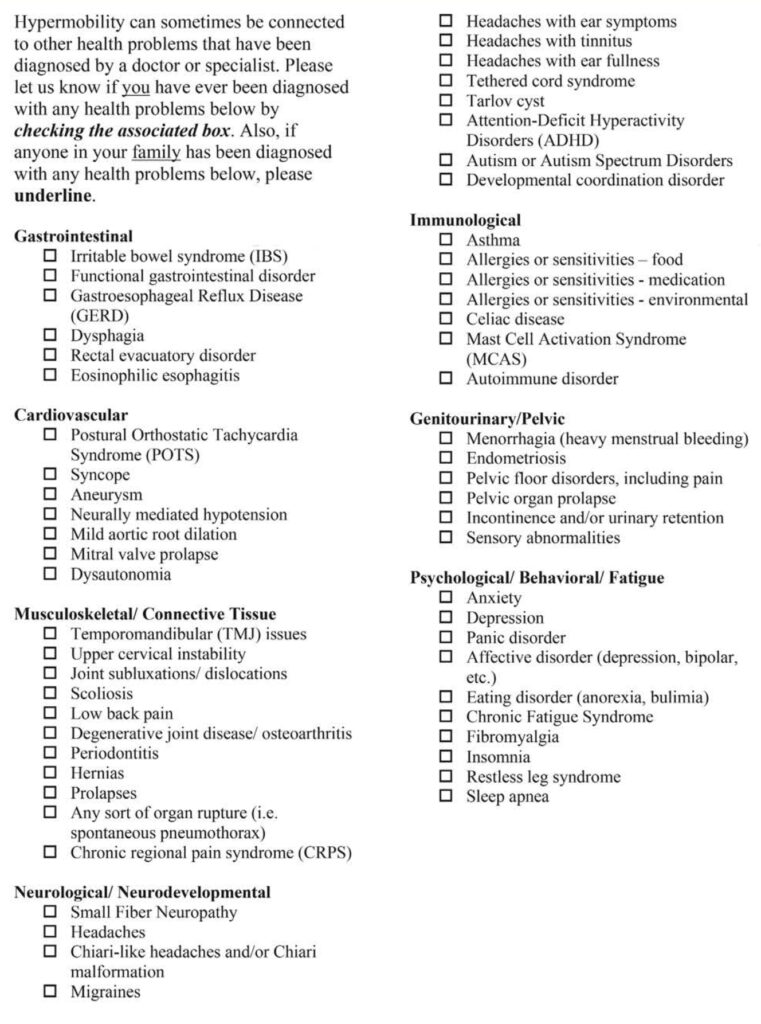

Below is the screening tool.

Taken as a whole, athletes participating in sport that present with signs and symptoms suggestive of EDS or other hypermobile syndromes, should have a comprehensive evaluation including joint mobility, muscular strength, balance and coordination, in addition to systemic issues including gastrointestinal, cardiology, psychiatry and neurology. The relative muscular weakness of athletes presenting with EDS and hypermobile syndromes may require additional time or effort to improve strength to be able to perform well and reduce injury risk. The good news is that strength training has a protective effect on joints, improves pain experience and reduces the risk of fall-related injuries. It is imperative that the athlete and their trainers keep an eye on fatigue levels, as individuals with EDS tend to fatigue earlier compared to their non-EDS peers. If athletes with EDS are managing an injury, it is usually best to continue activity with modifications, rather than completely stop.

While EDS and hypermobile syndromes are highly prevalent in the performing arts community, awareness of the associated complications and injury-risk factors is not fully understood with all health care providers. Seeking physical therapy treatment from a therapist that understands the physical and emotional demands of performing arts in addition to complications with EDS can make an enormous difference in an athletes career.

If you are an athlete experiencing EDS or hypermobility, and are concerned about returning to sport, give our office a call. Dr. Abbate has years of experience helping hundreds of professional performing artists at Royal Caribbean and Celebrity Cruises. If he can help them, he can help you!

Pain is a very common experience for people with EDS. This can be due to joint subluxation, arthralgia (joint-related), myofascial (muscle, skin) and visceral (internal organs) pain. This may progress to sensitization of the central nervous system, or how the brain perceives the pain experience. There is a strong association of pain in EDS with depression and anxiety.

Engagement in early childhood may help offset the presentation of chronic pain, poor sleep, deconditioning, orthostatic intolerance and nutritional deficiencies typically seen in this population.

Excessive joint laxity, or flexibility, is a classic presentation of EDS. While aesthetically pleasing, it increases the risk of joint related pathology (hip, ankle and shoulder instability) and certain injuries (labral tears, tendinopathies and joint degeneration). This often leads to more time off to recover from injuries.

There are several physical and historical screens that a physical therapist can administer. The Hypermobility Screening Tool can assist therapists in identifying systems-related dysfunction, and allow for proper referral to a health care provider. For example, an athlete complaining of headaches or dizziness with changes in body position, or after participating in strenuous activity, may warrant referral to a cardiologist. An athlete reporting frequent ankle sprains may require referral to an orthopedic.

The Beighton Score, Brighton criteria and 5-point screening questionnaire can be used to screen for joint hypermobility. These scoring systems identify joints that have excessive flexibility. It helps physical therapists identify which body parts need continued observation or focused intervention to prevent an injury from occurring. Other tests may include muscle function (strength and endurance) and balance (joint stability plays an important role in posture).

Below is a chart describing the types of tests physical therapists can utilize to help athletes experiencing symptoms of EDS.

Athletes participating in sports that are seeking medical attention for pain or weakness often complete screening tools. These screening tools can help facilitate referral to a proper medical provider, or help direct treatment by a physical therapist. It also provides a kind of “journal” for an athlete to measure over a specific time period. By keeping record of the day and symptoms, an athlete can visualize over the course of treatment what their symptoms are at any given time frame.

Below is the screening tool.

Taken as a whole, athletes participating in sport that present with signs and symptoms suggestive of EDS or other hypermobile syndromes, should have a comprehensive evaluation including joint mobility, muscular strength, balance and coordination, in addition to systemic issues including gastrointestinal, cardiology, psychiatry and neurology. The relative muscular weakness of athletes presenting with EDS and hypermobile syndromes may require additional time or effort to improve strength to be able to perform well and reduce injury risk. The good news is that strength training has a protective effect on joints, improves pain experience and reduces the risk of fall-related injuries. It is imperative that the athlete and their trainers keep an eye on fatigue levels, as individuals with EDS tend to fatigue earlier compared to their non-EDS peers. If athletes with EDS are managing an injury, it is usually best to continue activity with modifications, rather than completely stop.

While EDS and hypermobile syndromes are highly prevalent in the performing arts community, awareness of the associated complications and injury-risk factors is not fully understood with all health care providers. Seeking physical therapy treatment from a therapist that understands the physical and emotional demands of performing arts in addition to complications with EDS can make an enormous difference in an athletes career.

If you are an athlete experiencing EDS or hypermobility, and are concerned about returning to sport, give our office a call. Dr. Abbate has years of experience helping hundreds of professional performing artists at Royal Caribbean and Celebrity Cruises. If he can help them, he can help you!

There are a number of health conditions associated with EDS. Poor blood pressure regulation, fatigue, headaches, anxiety and depression may be misinterpreted or downplayed by medical professionals.

Orthostatic intolerance (the ability for the body to maintain adequate blood pressure during or after activity) is present in about half of the population with EDS. Symptoms include dizziness, pre syncope, syncope, headaches, nausea, sweating or changes in blood pressure upon standing or after exercise.

Allergy-like symptoms of the skin (rashes), stomach (upset stomach), neuromuscular tissues (fatigue), airways (difficulty breathing), cardiovascular (abnormal heart rate response) and central nervous system (anxiety, depression) may appear at certain over an athletes career. Athletes may experience one or any combination of systemic issues. Nutritional deficiencies may present due to reflux, nausea, vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation and bloating. This may affect energy availability leading to fatigue and limiting tissue healing necessary after strenuous activity.

Pain is a very common experience for people with EDS. This can be due to joint subluxation, arthralgia (joint-related), myofascial (muscle, skin) and visceral (internal organs) pain. This may progress to sensitization of the central nervous system, or how the brain perceives the pain experience. There is a strong association of pain in EDS with depression and anxiety.

Engagement in early childhood may help offset the presentation of chronic pain, poor sleep, deconditioning, orthostatic intolerance and nutritional deficiencies typically seen in this population.

Excessive joint laxity, or flexibility, is a classic presentation of EDS. While aesthetically pleasing, it increases the risk of joint related pathology (hip, ankle and shoulder instability) and certain injuries (labral tears, tendinopathies and joint degeneration). This often leads to more time off to recover from injuries.

There are several physical and historical screens that a physical therapist can administer. The Hypermobility Screening Tool can assist therapists in identifying systems-related dysfunction, and allow for proper referral to a health care provider. For example, an athlete complaining of headaches or dizziness with changes in body position, or after participating in strenuous activity, may warrant referral to a cardiologist. An athlete reporting frequent ankle sprains may require referral to an orthopedic.

The Beighton Score, Brighton criteria and 5-point screening questionnaire can be used to screen for joint hypermobility. These scoring systems identify joints that have excessive flexibility. It helps physical therapists identify which body parts need continued observation or focused intervention to prevent an injury from occurring. Other tests may include muscle function (strength and endurance) and balance (joint stability plays an important role in posture).

Below is a chart describing the types of tests physical therapists can utilize to help athletes experiencing symptoms of EDS.

Athletes participating in sports that are seeking medical attention for pain or weakness often complete screening tools. These screening tools can help facilitate referral to a proper medical provider, or help direct treatment by a physical therapist. It also provides a kind of “journal” for an athlete to measure over a specific time period. By keeping record of the day and symptoms, an athlete can visualize over the course of treatment what their symptoms are at any given time frame.

Below is the screening tool.

Taken as a whole, athletes participating in sport that present with signs and symptoms suggestive of EDS or other hypermobile syndromes, should have a comprehensive evaluation including joint mobility, muscular strength, balance and coordination, in addition to systemic issues including gastrointestinal, cardiology, psychiatry and neurology. The relative muscular weakness of athletes presenting with EDS and hypermobile syndromes may require additional time or effort to improve strength to be able to perform well and reduce injury risk. The good news is that strength training has a protective effect on joints, improves pain experience and reduces the risk of fall-related injuries. It is imperative that the athlete and their trainers keep an eye on fatigue levels, as individuals with EDS tend to fatigue earlier compared to their non-EDS peers. If athletes with EDS are managing an injury, it is usually best to continue activity with modifications, rather than completely stop.

While EDS and hypermobile syndromes are highly prevalent in the performing arts community, awareness of the associated complications and injury-risk factors is not fully understood with all health care providers. Seeking physical therapy treatment from a therapist that understands the physical and emotional demands of performing arts in addition to complications with EDS can make an enormous difference in an athletes career.

If you are an athlete experiencing EDS or hypermobility, and are concerned about returning to sport, give our office a call. Dr. Abbate has years of experience helping hundreds of professional performing artists at Royal Caribbean and Celebrity Cruises. If he can help them, he can help you!

Secondary health complications due to connective tissue disorders include tendinopathy, joint subluxations/dislocations, scoliosis and arthritis. Additionally the autonomic, cardiovascular, skin and immune systems may be affected.

There are a number of health conditions associated with EDS. Poor blood pressure regulation, fatigue, headaches, anxiety and depression may be misinterpreted or downplayed by medical professionals.

Orthostatic intolerance (the ability for the body to maintain adequate blood pressure during or after activity) is present in about half of the population with EDS. Symptoms include dizziness, pre syncope, syncope, headaches, nausea, sweating or changes in blood pressure upon standing or after exercise.

Allergy-like symptoms of the skin (rashes), stomach (upset stomach), neuromuscular tissues (fatigue), airways (difficulty breathing), cardiovascular (abnormal heart rate response) and central nervous system (anxiety, depression) may appear at certain over an athletes career. Athletes may experience one or any combination of systemic issues. Nutritional deficiencies may present due to reflux, nausea, vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation and bloating. This may affect energy availability leading to fatigue and limiting tissue healing necessary after strenuous activity.

Pain is a very common experience for people with EDS. This can be due to joint subluxation, arthralgia (joint-related), myofascial (muscle, skin) and visceral (internal organs) pain. This may progress to sensitization of the central nervous system, or how the brain perceives the pain experience. There is a strong association of pain in EDS with depression and anxiety.

Engagement in early childhood may help offset the presentation of chronic pain, poor sleep, deconditioning, orthostatic intolerance and nutritional deficiencies typically seen in this population.

Excessive joint laxity, or flexibility, is a classic presentation of EDS. While aesthetically pleasing, it increases the risk of joint related pathology (hip, ankle and shoulder instability) and certain injuries (labral tears, tendinopathies and joint degeneration). This often leads to more time off to recover from injuries.

There are several physical and historical screens that a physical therapist can administer. The Hypermobility Screening Tool can assist therapists in identifying systems-related dysfunction, and allow for proper referral to a health care provider. For example, an athlete complaining of headaches or dizziness with changes in body position, or after participating in strenuous activity, may warrant referral to a cardiologist. An athlete reporting frequent ankle sprains may require referral to an orthopedic.

The Beighton Score, Brighton criteria and 5-point screening questionnaire can be used to screen for joint hypermobility. These scoring systems identify joints that have excessive flexibility. It helps physical therapists identify which body parts need continued observation or focused intervention to prevent an injury from occurring. Other tests may include muscle function (strength and endurance) and balance (joint stability plays an important role in posture).

Below is a chart describing the types of tests physical therapists can utilize to help athletes experiencing symptoms of EDS.

Athletes participating in sports that are seeking medical attention for pain or weakness often complete screening tools. These screening tools can help facilitate referral to a proper medical provider, or help direct treatment by a physical therapist. It also provides a kind of “journal” for an athlete to measure over a specific time period. By keeping record of the day and symptoms, an athlete can visualize over the course of treatment what their symptoms are at any given time frame.

Below is the screening tool.

Taken as a whole, athletes participating in sport that present with signs and symptoms suggestive of EDS or other hypermobile syndromes, should have a comprehensive evaluation including joint mobility, muscular strength, balance and coordination, in addition to systemic issues including gastrointestinal, cardiology, psychiatry and neurology. The relative muscular weakness of athletes presenting with EDS and hypermobile syndromes may require additional time or effort to improve strength to be able to perform well and reduce injury risk. The good news is that strength training has a protective effect on joints, improves pain experience and reduces the risk of fall-related injuries. It is imperative that the athlete and their trainers keep an eye on fatigue levels, as individuals with EDS tend to fatigue earlier compared to their non-EDS peers. If athletes with EDS are managing an injury, it is usually best to continue activity with modifications, rather than completely stop.

While EDS and hypermobile syndromes are highly prevalent in the performing arts community, awareness of the associated complications and injury-risk factors is not fully understood with all health care providers. Seeking physical therapy treatment from a therapist that understands the physical and emotional demands of performing arts in addition to complications with EDS can make an enormous difference in an athletes career.

If you are an athlete experiencing EDS or hypermobility, and are concerned about returning to sport, give our office a call. Dr. Abbate has years of experience helping hundreds of professional performing artists at Royal Caribbean and Celebrity Cruises. If he can help them, he can help you!

Secondary health complications due to connective tissue disorders include tendinopathy, joint subluxations/dislocations, scoliosis and arthritis. Additionally the autonomic, cardiovascular, skin and immune systems may be affected.

There are a number of health conditions associated with EDS. Poor blood pressure regulation, fatigue, headaches, anxiety and depression may be misinterpreted or downplayed by medical professionals.

Orthostatic intolerance (the ability for the body to maintain adequate blood pressure during or after activity) is present in about half of the population with EDS. Symptoms include dizziness, pre syncope, syncope, headaches, nausea, sweating or changes in blood pressure upon standing or after exercise.

Allergy-like symptoms of the skin (rashes), stomach (upset stomach), neuromuscular tissues (fatigue), airways (difficulty breathing), cardiovascular (abnormal heart rate response) and central nervous system (anxiety, depression) may appear at certain over an athletes career. Athletes may experience one or any combination of systemic issues. Nutritional deficiencies may present due to reflux, nausea, vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation and bloating. This may affect energy availability leading to fatigue and limiting tissue healing necessary after strenuous activity.

Pain is a very common experience for people with EDS. This can be due to joint subluxation, arthralgia (joint-related), myofascial (muscle, skin) and visceral (internal organs) pain. This may progress to sensitization of the central nervous system, or how the brain perceives the pain experience. There is a strong association of pain in EDS with depression and anxiety.

Engagement in early childhood may help offset the presentation of chronic pain, poor sleep, deconditioning, orthostatic intolerance and nutritional deficiencies typically seen in this population.

Excessive joint laxity, or flexibility, is a classic presentation of EDS. While aesthetically pleasing, it increases the risk of joint related pathology (hip, ankle and shoulder instability) and certain injuries (labral tears, tendinopathies and joint degeneration). This often leads to more time off to recover from injuries.

There are several physical and historical screens that a physical therapist can administer. The Hypermobility Screening Tool can assist therapists in identifying systems-related dysfunction, and allow for proper referral to a health care provider. For example, an athlete complaining of headaches or dizziness with changes in body position, or after participating in strenuous activity, may warrant referral to a cardiologist. An athlete reporting frequent ankle sprains may require referral to an orthopedic.

The Beighton Score, Brighton criteria and 5-point screening questionnaire can be used to screen for joint hypermobility. These scoring systems identify joints that have excessive flexibility. It helps physical therapists identify which body parts need continued observation or focused intervention to prevent an injury from occurring. Other tests may include muscle function (strength and endurance) and balance (joint stability plays an important role in posture).

Below is a chart describing the types of tests physical therapists can utilize to help athletes experiencing symptoms of EDS.

Athletes participating in sports that are seeking medical attention for pain or weakness often complete screening tools. These screening tools can help facilitate referral to a proper medical provider, or help direct treatment by a physical therapist. It also provides a kind of “journal” for an athlete to measure over a specific time period. By keeping record of the day and symptoms, an athlete can visualize over the course of treatment what their symptoms are at any given time frame.

Below is the screening tool.

Taken as a whole, athletes participating in sport that present with signs and symptoms suggestive of EDS or other hypermobile syndromes, should have a comprehensive evaluation including joint mobility, muscular strength, balance and coordination, in addition to systemic issues including gastrointestinal, cardiology, psychiatry and neurology. The relative muscular weakness of athletes presenting with EDS and hypermobile syndromes may require additional time or effort to improve strength to be able to perform well and reduce injury risk. The good news is that strength training has a protective effect on joints, improves pain experience and reduces the risk of fall-related injuries. It is imperative that the athlete and their trainers keep an eye on fatigue levels, as individuals with EDS tend to fatigue earlier compared to their non-EDS peers. If athletes with EDS are managing an injury, it is usually best to continue activity with modifications, rather than completely stop.

While EDS and hypermobile syndromes are highly prevalent in the performing arts community, awareness of the associated complications and injury-risk factors is not fully understood with all health care providers. Seeking physical therapy treatment from a therapist that understands the physical and emotional demands of performing arts in addition to complications with EDS can make an enormous difference in an athletes career.

If you are an athlete experiencing EDS or hypermobility, and are concerned about returning to sport, give our office a call. Dr. Abbate has years of experience helping hundreds of professional performing artists at Royal Caribbean and Celebrity Cruises. If he can help them, he can help you!

The International Consortium on the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes defined the following diagnostic criteria:

Secondary health complications due to connective tissue disorders include tendinopathy, joint subluxations/dislocations, scoliosis and arthritis. Additionally the autonomic, cardiovascular, skin and immune systems may be affected.

There are a number of health conditions associated with EDS. Poor blood pressure regulation, fatigue, headaches, anxiety and depression may be misinterpreted or downplayed by medical professionals.

Orthostatic intolerance (the ability for the body to maintain adequate blood pressure during or after activity) is present in about half of the population with EDS. Symptoms include dizziness, pre syncope, syncope, headaches, nausea, sweating or changes in blood pressure upon standing or after exercise.

Allergy-like symptoms of the skin (rashes), stomach (upset stomach), neuromuscular tissues (fatigue), airways (difficulty breathing), cardiovascular (abnormal heart rate response) and central nervous system (anxiety, depression) may appear at certain over an athletes career. Athletes may experience one or any combination of systemic issues. Nutritional deficiencies may present due to reflux, nausea, vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation and bloating. This may affect energy availability leading to fatigue and limiting tissue healing necessary after strenuous activity.

Pain is a very common experience for people with EDS. This can be due to joint subluxation, arthralgia (joint-related), myofascial (muscle, skin) and visceral (internal organs) pain. This may progress to sensitization of the central nervous system, or how the brain perceives the pain experience. There is a strong association of pain in EDS with depression and anxiety.

Engagement in early childhood may help offset the presentation of chronic pain, poor sleep, deconditioning, orthostatic intolerance and nutritional deficiencies typically seen in this population.

Excessive joint laxity, or flexibility, is a classic presentation of EDS. While aesthetically pleasing, it increases the risk of joint related pathology (hip, ankle and shoulder instability) and certain injuries (labral tears, tendinopathies and joint degeneration). This often leads to more time off to recover from injuries.

There are several physical and historical screens that a physical therapist can administer. The Hypermobility Screening Tool can assist therapists in identifying systems-related dysfunction, and allow for proper referral to a health care provider. For example, an athlete complaining of headaches or dizziness with changes in body position, or after participating in strenuous activity, may warrant referral to a cardiologist. An athlete reporting frequent ankle sprains may require referral to an orthopedic.